- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Child of His Age

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I first encountered Francis Adams when various sharp or mordant observations from his The Australians kept cropping up in my reading about Henry Lawson and his times. For one thing, Adams’s widow, Edith (though there is apparently doubt about their marital status), invited Lawson and his wife, Bertha, to stay with her in the village of Harpenden while they looked for accommodation. Lawson duly rented ‘Spring Villa’ in Cowper Road, Harpenden, and thus began his disastrous English sojourn.

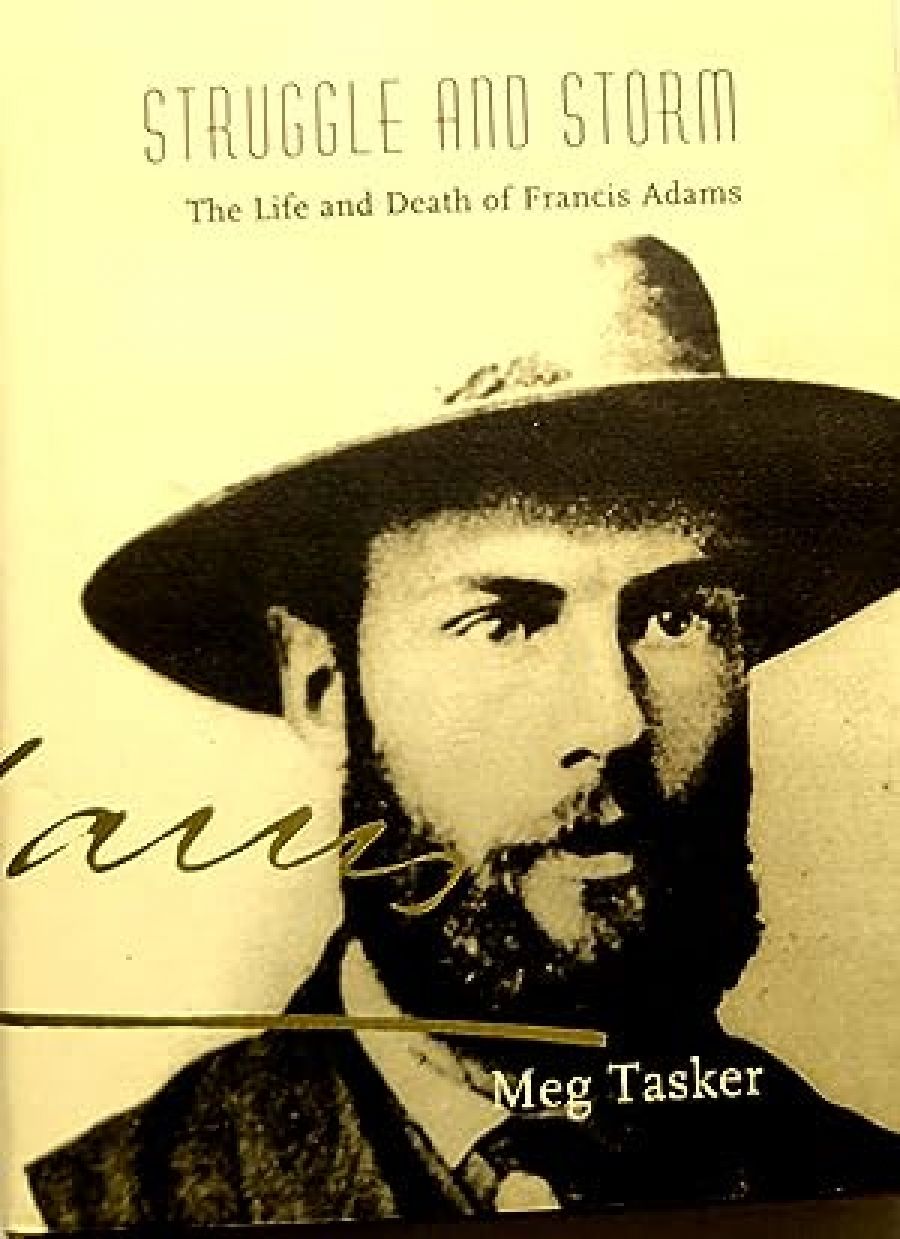

- Book 1 Title: Struggle and Storm

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and death of Francis Adams

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.95 hb, 259 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

On at least two scores, Francis Adams looms as, biographically, a hard ask. First, the record of his life and activities is ‘scanty’, as Tasker admits; second, as a writer of prose and as a poet, he was mostly second rate, though admired by various critics and pundits from time to time. Tasker is judicious about Adams’s capacities. She makes the case for his novels and poetry. Probably, like any engaged biographer after years of obsession and search, she makes it a little too enthusiastically, but the overall impression as she navigates his prolific literary output is of scholarly restraint and, I would say, of getting it right. She recognises that, rather like Andrew Motion’s recent fictional/ biographical hero, Wainewright the poisoner, Adams was also of great colonial fascination because of his cultural affiliations, contacts and interests. ‘He ... presents, for the contemporary reader and scholar, a link between the worlds of Matthew Arnold and Henry Lawson, Heinrich Heine and Adam Lindsay Gordon, Balzac and William Lane, Charles Baudelaire and Marcus Clarke.’ It is one of the real achievements of Storm and Struggle that it brings to life the cultural and political ferment that Adams so much enjoyed, in which he was frequently central and of which, at his best, he was such an astute observer. His ‘charisma’ – a quality Tasker mentions a couple of times – resided not only in his undeniable intellectual acuity, broad literary range of reference and tireless application (despite constant and worsening illness), but also and pre-eminently in the way he seemed to be a confident and assured cynosure for the great issues of the day. He was, as Tasker clearly demonstrates, genuinely ‘an influential child of his age’.

There is another way in which Storm and Struggle is briefly reminiscent of Motion’s Wainewright The Poisoner. Both biographers begin by agonising about the nature of the task, of biography’s possibly (or certainly) diminishing authority at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Motion has admitted to a personal collapse of faith in biography (as has Victoria Glendinning recently) and opts for what turns out to be a fictional method with conventional footnotes. Tasker worries about ‘textual reincarnation’, about transcending the ‘written accounts, medical records, official documents’, the texts, in short, on which inevitably she must depend. ‘Researching a biography,’ she says, ‘is in many respects an effort to go beyond the textual … The way of the biographer,’ she says, quoting Richard Holmes, ‘is not to re-create the past, but somehow to “produce the living effect, while remaining true to the dead fact”. But what is the living effect? It’s hard enough to find the dead facts, and the living effect that most biographers produce must be a combination of research and intuition, reconstruction and imagination.’

This seems to me, like Motion’s preliminary convolutions, to be running on the spot. The arguments about biography’s possibly tendentious relationship with fiction, about what the biographer’s options are when faced with a paucity of evidence and about the nature and presence of the biographer figure, have had a significant airing in this country over the past decade or so (even though Andrew Motion writes as if he were the first to burst into that shifting sea) and, while they have been by no means put to rest, it’s now quite difficult to rehearse them and still sound fresh. Likewise: ploys to have the biographer intrude into, stride alongside or be in some other relationship with the narrative. Tasker’s manoeuvre is to introduce what are sometimes asides, some-times elaborations, sometimes quizzical wonderings, in a different font: ‘it’s a bloody good story,’ she says (rightly) of her narrative in the first of these intrusions, explaining that ‘you’ll find me butting in from time to time with off-the-record comments – but I can get away with it by using a different font, can’t I?’

Well, maybe not. The trouble with these ‘asides’ is that they often don’t sound different enough from the prevailing ‘voice’ or, conversely, that self-conscious attempts at trenchant difference – like ‘it’s a bloody good story’ – draw attention to themselves uneasily. At other times (inevitably, it seems to me, in my experience of this particular recourse), these sections sound arch. Tasker’s own style, in the main text, is in any case unfailingly charming, witty and incisive and many of the different-font excursions could have been profitably retained as part of the narrative with only very small refining.

Francis Adams is a difficult case: there are longueurs lurking in his story (e.g. his championing of Sir Thomas McIlwraith) and dark, fascinating places that remain, no doubt necessarily, obscure (his marriages, his attitude to intimacy, his inner life of illness). But Meg Tasker has tackled the known and the unknown territories with great skill, energy and an irrepressible wit that do justice to Francis Adams’s short, sombre, yet – as this biography shows – somehow representative and influential life.

Comments powered by CComment