- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Club Med of the Mind

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1897, Winston Churchill published his only novel, Savrola, a racy account of revolution and romantic intrigue in the imaginary South American republic of Laurania. The book traces the rise, fall, and rise of Savrola, a gifted politician and charismatic orator who outmanoeuvres a despotic military regime to restore democratic rule to the undeserving masses, only to fall prey to a socialist revolution before returning in triumph and instituting an age of peace and plenty.

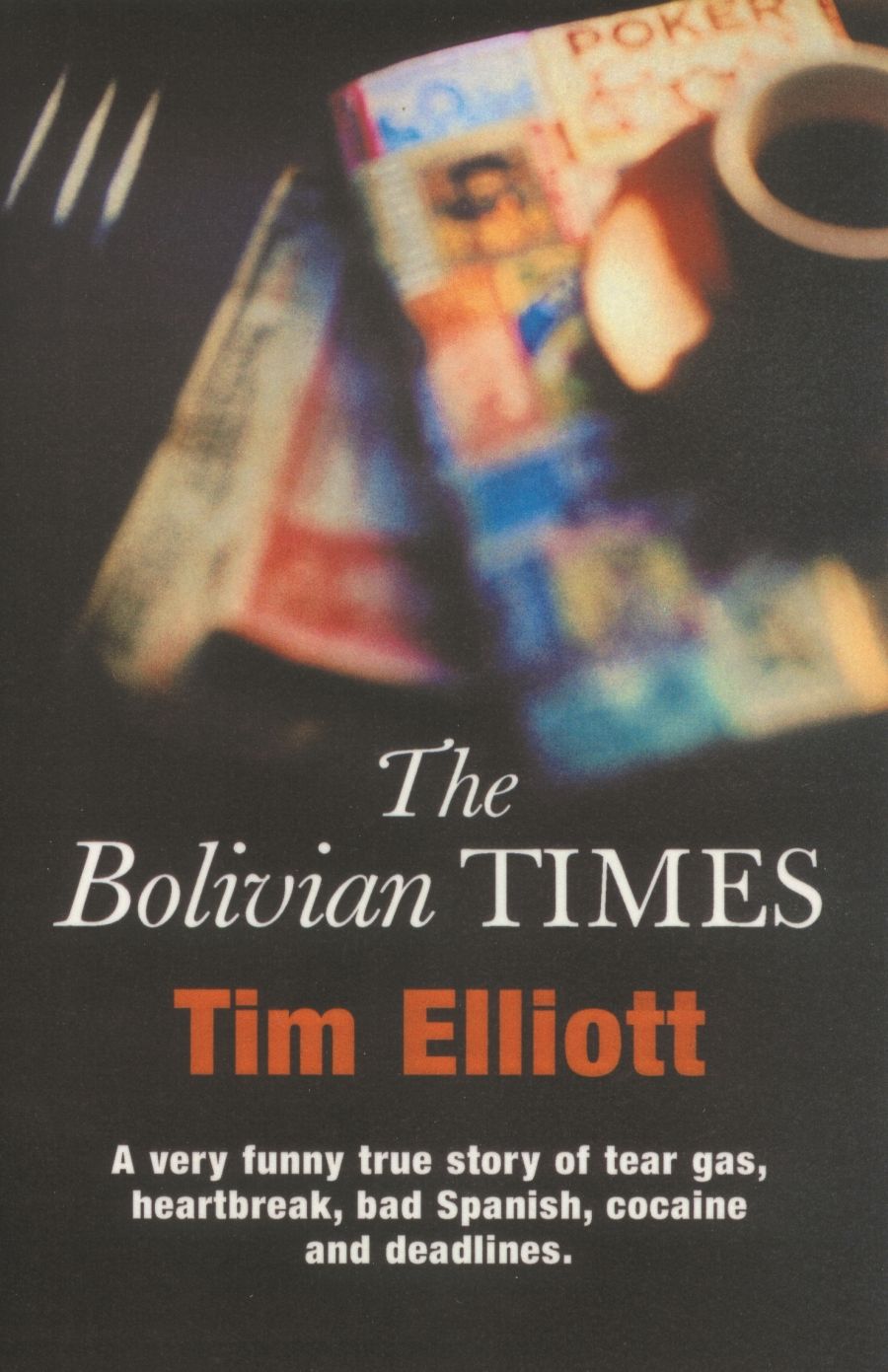

- Book 1 Title: The Bolivian Times

- Book 1 Biblio: $19.95 pb, 263 pp

When he wrote the book, Churchill was a twenty-three-year-old cavalry officer with the 4th Hussars in India. Latin America was, for him, as for the vast majority of his contemporaries, little more than a blank space on the map, most notable for its almost complete freedom from the pink shade of British imperial dominion. Indeed, he noted in his autobiography that the novel might just as well have been set in the Balkans, another all-purpose trouble spot with a regular round of coups, catastrophes, and revolutions, well-supplied with a stock cast of schemers, squealers, crooks, cowards, and an ever-malleable mob. Widespread ignorance about Latin America, then, was not a hindrance to Churchill’s project but an ideal basis on which to proceed. Unencumbered by fact, he could shape Latin America in accordance with the demands of his own particular needs. Hence, the cavalier politics and piratical principals of Laurania provided him with a symbolic site for his own fantasy of political fulfilment, a safe place to rehearse, albeit imaginatively, for the life that awaited him.

If the peculiarly self-regarding nature of Churchill’s political fantasy is a matter for comment, his treatment of Latin America has attracted little attention. Throughout the twentieth century, as in the preceding one, Latin America served British and American writers as a locus for the enactment of the political and social imaginary: a physical and psychological blank in which the shifting fears and fantasies of the English-speaking West might be explored, embodied, and enacted. Yet more recently, and Tim Elliott’s The Bolivian Times is a good case in point, Latin America has featured in literatures written in English less as an ideological playground, an imagined place of authentic and extreme experience, and more as an exotic setting for familiar stories of domestic discontent and personal growth. What was once a raw psychological frontier has become a Club Med of the mind. What are we to make of this? While it may look like the last rites for colonial arrogance, it might be better to hold off on the celebrations. Tim Elliott’s account indicates that the move from revolution to romance has done little to lift the profile of Latin America or to improve the lot of its people in English-language treatments of the continent.

After splitting up with his girlfriend on a trip around South America, Elliott, a Sydney journalist, spent several months working on Bolivia’s only English-language daily, the Bolivian Times. He gets the job, he assures us, in part or at least in spite of his execrable Spanish. It is clear, as such, where the focus of the book lies. It is also clear that we will end up learning far more about Elliott than we ever will about Bolivia. The country is sketched in a series of broad brush strokes, from the rainy greys of wintry La Paz, through the green of coca country, to the sodden muddy browns of the Amazon districts.

For a book with some impressive geographical coverage – Elliott spends a good deal of time on assignment out of La Paz – it is striking how scant a vision of Bolivia one derives from it. Elliott’s Bolivia is a coca-fuelled chaos: the country’s only industry, its only political, social, or cultural issues, as presented here, are cocaine production and the government’s endeavours to eradicate it or to deal with the corruption arising from it. His Bolivians (Elliott’s girlfriend, Maria, excepted) are the usual Latino suspects: dealers, smugglers, snorters, soldiers and, most pathetically of all, the impoverished growers for whom coca is a vital cash crop, the surest means to subsistence.

Elliott’s portrayal of the other end of the supply chain is neatly revealing: the nasal gymnasts of La Paz seem hardly better off than the coca growers. If one is struggling to put food on the table, the others are hell-bent on avoiding the monotony of having to do so by determinedly getting off their faces. The various scenes of sex and snorting are tinged with melancholy: they are almost elegiac at times. Everybody has lost something: love, innocence, a vision of the country. Elliott’s Bolivia thus emerges as an emblem of the imperfect world we all occupy and the burdens we must all learn to carry.

But this is neither a political nor a travel book. So what is it? For Elliott, the job on the Bolivian Times is a means to a little moral credibility, a way of proving to himself that he is over his girlfriend, that he can function without her, and then go home. The real journey, then, is towards self-knowledge of a limited kind. It is, in all fairness, neither a lengthy nor an especially scenic odyssey. As such, the journey has to be teased out with a series of geographical and comic detours, set pieces deflating the unfulfilled promise of real drug action.

This is where the book is at its best and, paradoxically, its worst. Elliott is a gifted comic writer: direct, appealing, with a perfect sense of timing, and an ear for the well-turned oath. Yet after a while, his use of Bolivia as the straight man for his gags becomes a little gratuitous, and one feels that it might all, just as reasonably, have been set in Sydney. Is this what the liberators of the continent dreamed of? Is the subordinate role in a comedy of manners an escape from the shackles of colonial dependence or just a new and more fashionable form of subjection?

‘Did I tell you the one about Bolivar …?’

Comments powered by CComment