- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reviews

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Breezy Bell

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As it happens, this is the sixth autobiographical work I’ve read in the last couple of months, and I’m led to reflect on the mode. If you do it in the form of publishing your diaries, as playwright Peter Nichols does in Diaries 1969–77, and are honest about it, then the absence of a time lag means you are perhaps more likely to render accurately the flavour of the experiences. If, like Henry James in A Small Boy and Others, you wait until you are seventy, the blurrings of time and the obfuscating convolutions of your late style may so distance the actualities that all the reader is left with is a meditation on the processes of memory. Nick Hornby, on the other hand, in Fever Pitch, combines meditation with sharply sensuous verbal snapshots of days spent on the ‘terraces’ cheering on the hapless Arsenal, and a life emerges – while he is still young enough to re-create the minutiae with vivid immediacy.

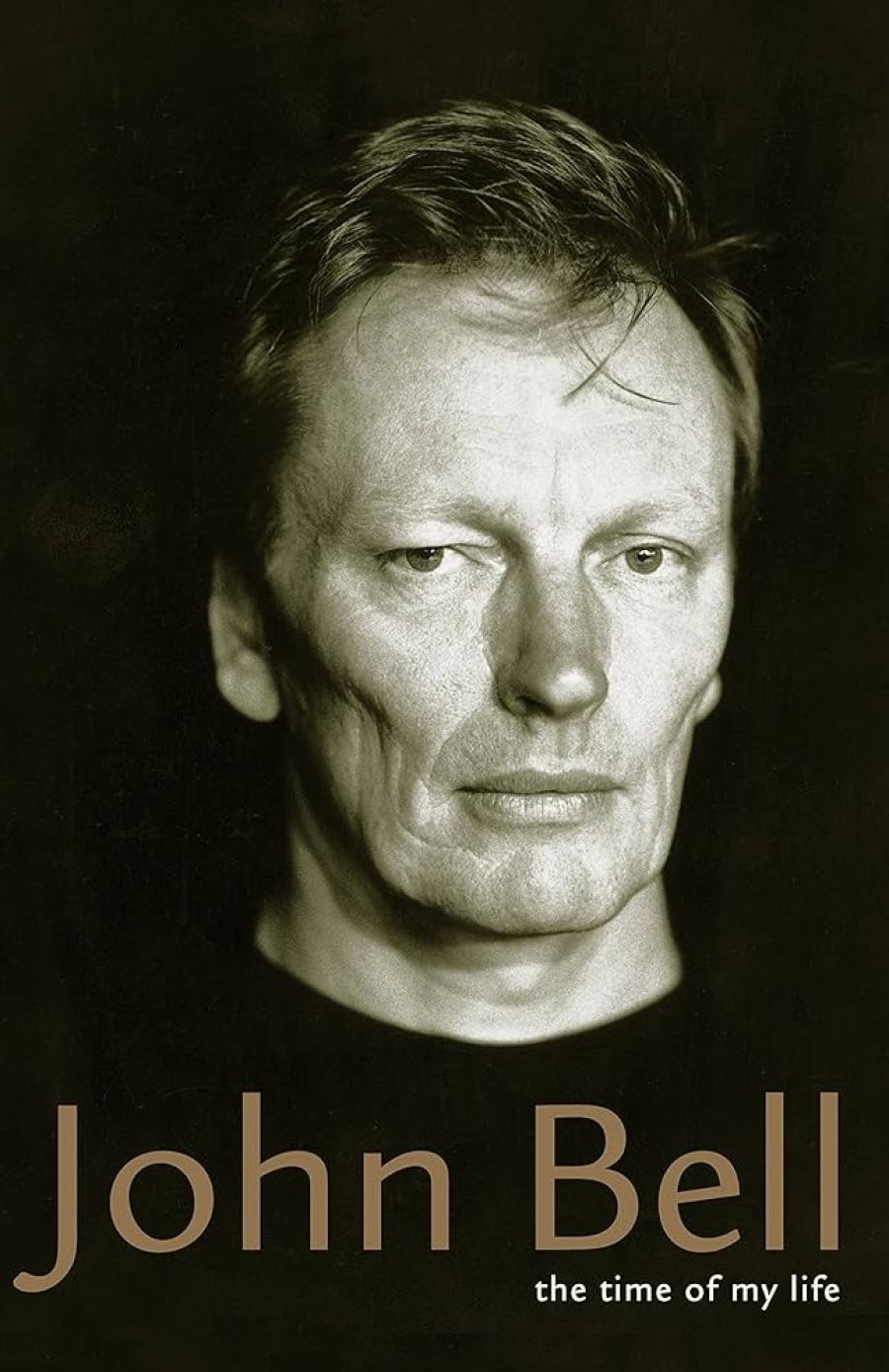

- Book 1 Title: The Time of My Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $45 hb, 276pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

My personal response to autobiography is to want the subject to grow up fairly fast and to start doing what made me want to read about him or her in the first place. Bell is reasonably obliging in this matter, though he does tend to see his childhood in an idealised golden glow, and he has to work at whipping up a bit of conflict, a sense of struggle, as he recounts his journey towards his vocation and Sydney’s Old Tote theatre. He tells us he was a ‘scholarship boy’ at Sydney University in the late 1950s, as if this made him seem like Pip in competition with Bentley Drummle; but virtually everyone at university then was on some sort of scholarship or bursary. It was no poignant sign of poverty, especially not if one’s father, like Bell’s, was a bank manager. These early chapters don’t seem sharply recalled: they are apt to be full of conventional recollections of a Christian Brothers’ education (‘Given how much time we spent praying and hymn-singing, it’s surprising we learned anything at all’, though there was the valuable advice that ‘you’ve always got time for a quick ejaculation!’), or of japes at university. It is all good-natured, affectionate and a bit bland.

The Time of My Life picks up when Bell grapples with the idea that Anglophilia and Australian republicanism might not be incompatible, a notion that feeds into the book’s greatest strength – and perhaps into Bell’s chief claim to an honoured place in Australian theatrical history. He heads for England in the early 1960s, and records with some vividness his excited recognition of the icons of Englishness he had grown up with second-hand, moving through London, the Bristol Old Vic School and the Royal Shakespeare Company at Stratford. At the latter, he was much influenced by Peter Hall’s finding in Shakespeare a relevance to contemporary realities, and this has been one of Bell’s own strengths. He is generous and explicit about what he learned from British directors and actors (Olivier’s Henry V was his first inspiration), and their achievements push him to frame his own key question: ‘Does Australia need Shakespeare?’ The rest of his book, detailing his time at NIDA, as a drama instructor, and at the Nimrod as director and actor, and then as artistic director of his own Bell Shakespeare Company, chronicles his efforts to produce an Australian theatre that was ‘rough, rude, popular and shocking’.

As he considers how to free Australian theatre’s approach to world drama, and especially Shakespearean drama, from the shackles of a tradition forged elsewhere, he offers some serious insights into a vexed problem. He realises that a director who is always searching for a ‘new’ approach to canonical works risks being called trendy, while one who faithfully sticks to doublet-and-hose in the middle distance is likely to be thought merely fusty. The Nimrod years saw the production not just of classics, but of over a hundred Australian plays, thus ‘help[ing] popularise the notion of an Australian theatre, an Australian voice, and this in turn had a positive impact on the fledgling local film industry’.(Sadly, he took almost no part in the latter.)

However, it is his work with the company that bears his name for which he will be best remembered, taking it on tour and into schools, reinforcing his conviction that Shakespeare can be and – because of the mirror he holds up to mankind – should be made accessible to the widest possible audience. His work in running the company, along with his intellectual grapplings with, say, Hamlet or Shylock (and some rather bizarre thoughts on the Macbeths), give The Time of My Life its chief distinction. The crusading zeal doesn’t descend to didacticism and, if there have been miscalculations, then that is the price paid for looking at famous works with a fresh eye.

So, Bell’s professional and personal growth are enmeshed. There is in the background of Bell’s story, if not, presumably, of his life, a long and contented marriage with actress Anna Volska, which produced two daughters who have also sought theatrical careers. One forgets for chapters at a time about these important figures in his landscape. The ‘personal’ seems to have been too struggle-free to make riveting reading; recording the ‘professional’ allows us to see a lively mind in action.

Comments powered by CComment