- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Andreas Gaile reviews 'My Life as a Fake' by Peter Carey

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To an outside observer of the Australian literary and cultural scene, the Ern Malley hoax is one of those spin-offs in the Australian experience that keep on conjuring up Mark Twain’s famous dictum of the nature of the country’s history: ‘It does not read like history, but like the most beautiful lies ...

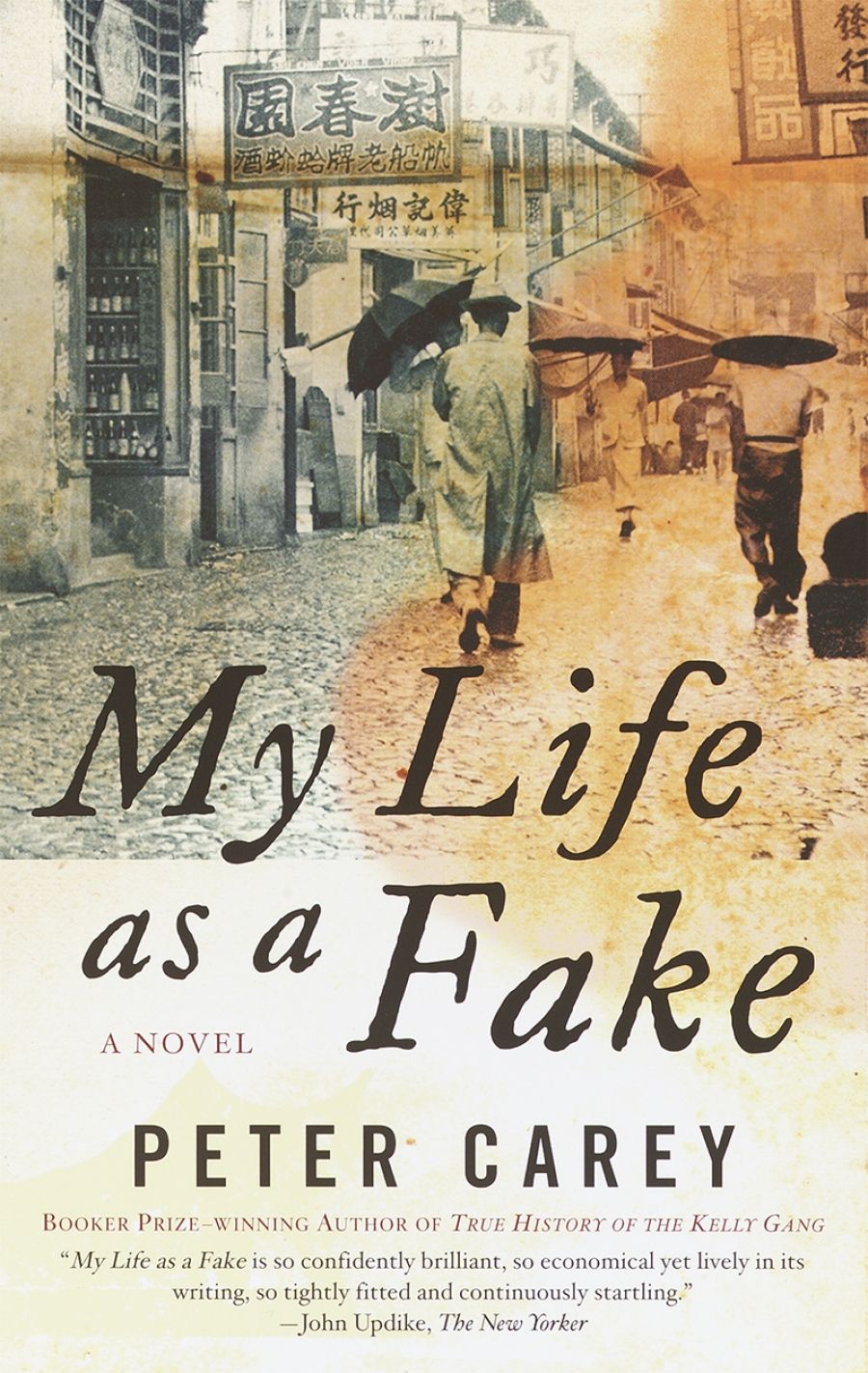

- Book 1 Title: My Life as a Fake

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, $45 hb, 288 pp, 1740512464

My Life as a Fake comes along as a critical investigation of one of the most legendary figures in twentieth-century Australia. The novel features decidedly more than the ‘certain connections’ between the real and the fictional fake, Ern Malley and Bob McCorkle, which Carey avows in his Author’s Note. Almost all of the main actors of the Ern Malley hoax are there, assembled to witness the faked poet’s hitherto unknown life: the hoaxers McAuley and Stewart, in the novel condensed to the figure of the psychotic poet Christopher Chubb; the faked poet Ern Malley himself, renamed Bob McCorkle, along with his sister Ethel (alias Beatrice McCorkle); Malley’s publisher, Max Harris (incidentally the co-founder of Australian Book Review, in its first incarnation), thinly disguised as David Weiss; and the representatives of South Australian law enforcement who tried Harris for publishing obscene material: the chief witness Detective Vogelesang (undisguised), as well as Alfred Cousins starring as Judge L.E. Clarke.

Anchored in the well-known facts of the Malley hoax, My Life as a Fake tells the story of Sarah Wode-Douglass who, on a trip to Malaysia, chances upon Chubb reading a rare copy of Rilke’s Sonette an Orpheus. Hopelessly stranded in a bicycle shop in Kuala Lumpur, Chubb subsequently tells her the ‘story of his sad, unlikely life’ and entangles Wode-Douglass, editor of an ailing literary magazine, into the mysteries of McCorkle’s secret life. For the rest of the novel, the reader follows the narrator Wode-Douglass on her quest for the literary genius who came forth into the world as a clever literary prank at the age of twenty-four, and now tracks down his maker demanding a birth certificate to legitimate his faked existence. In a variation on the Frankenstein motif, Chubb’s phantom overcomes his creator to be ‘the greatest writer ever born’ and eventually, in an ironic twist of fortunes, tricks his master into living his own lie.

As soon as McCorkle breaks free from the facts of the real hoax, as soon as the phantom is born out of the lacuna of literary history, Carey’s fiction turns into a haunting trip through the memories of its main characters, alternating between the narrative frame, the story of the narrator’s attempt at uncovering the mysteries of McCorkle’s faked life, and the embedded narratives of those who are drawn into the phantom’s abysmal world. Set in the suffocatingly narrow lanes of Kuala Lumpur and the Malaysian jungle, where Chubb tries to hunt down what started as a clever figment of his imagination, the narrative exudes an air of mystery throughout. Its Asiatic setting serves as a backcloth to the fakery, highlighting those complications of McCorkle’s life that leave the reader as well as the narrator somewhat nonplussed. The one fact that the narrator, a self-proclaimed ‘sad frien[d] of Truth’ of the Miltonian kind, can be certain of at the end of the novel is ‘that McCorkle had a physical existence and it was separate from Chubb’s’. All the rest is a ‘horrid puzzle’ that ends with Chubb literally dismembered by the frantic custodians of his fake’s memory, and McCorkle himself dying of Graves disease, originally his maker’s ‘joke, a pun, the disease of Robert Graves and T.S. Eliot, all the mumbo-jumbo men’.

But what can we expect, if not a puzzle, from the fictionalisation of a real fake’s life with its multi-layered skeins of truth, falsity, and the complications of the philosophical aporia behind it. The hoax affords Carey, a master of postmodernist explorations into the binarisms of Western thought, the right material to stage a discourse on what constitutes categories such as truth and fiction, and what distinguishes the original from the fake, the maker from his monster, the madman from the sane.

It is in places where such essential boundaries are blurred that Carey’s novel is at its best. Although the non-Australian setting presents a radical departure from his previous novels, with their Australian locales and colours, a number of the narrative strategies and motifs of My Life as a Fake will be familiar to Carey readers. Like so many of the characters that people the writer’s other fictions, McCorkle is inextricably caught in someone else’s narrative contrivance. Also, it must be remembered that the post-structuralist-induced conflation of categories such as truth and fiction is a recurrent concern in the author’s fictions. After all, Carey is the author who has gone down into literary history as the creator of the notorious 139-year-old King of Liars, Herbert Badgery (in Illywhacker), and the writer who, after the publication of hundreds of books on the Kelly Gang, eventually delivered the bushrangers’ true history in 2001 – in the form of a fiction.

There is far more to My Life as a Fake, though, than a postmodernist’s abstract musings on the nature of truth and fiction. The novel is a direct engagement with a literary and cultural potato that has remained scaldingly hot in a country long haunted by a serious form of the ‘cultural cringe’. It is this cultural uncertainty that animated the prankster Chubb in the beginning:

The boy from Haberfield [Chubb] was known for the small number of poets he would allow into his library: Donne, Shakespeare, Rilke, Mallarmé. He had been born into a second-rate culture, or so he thought, and one can see in that austere bookshelf all the passion that later led to the birth of Bob McCorkle – a terror that he might be somehow tricked into admiring the second-rate, the derivative, the shallow, the provincial.

The topos of fakery thus serves the author as an intricate metaphor for Australia’s notorious cultural belatedness, its abject status as a country of second-hand thriving on cultural imports that tragically defer its coming of age.

In the moral universe of Carey’s novel, McCorkle comes to stand as an avenger of cultural narrow-mindedness, with his oeuvre suddenly ‘becom[ing] true, the song of the autodidact, the colonial, the damaged beast of the antipodes’. Viewed against this background, McCorkle’s monstrosity appears as a form of retaliation both for the lies of his creator Chubb and, importantly so, for the excessive cultural philistinism of those who outlawed his poems. In an act of ventriloquism, McCorkle hence formulates the real-life author’s indictment: ‘How could we let that be? How could any of us stand there and let that crime be done? ... Would any civilised nation do such a thing? They have made me hate my country. I tried to speak up, but the fascists evicted me.’

To sum up, My Life as a Fake once again proves the assessment of a previous reviewer who held that Carey never writes the same novel twice. With its gothic gloom and its fascination for the freakish, it presents a radical imaginative departure from the verisimilitude of novels such as True History of the Kelly Gang and Oscar and Lucinda, or the journalistic realism of a novel like The Tax Inspector. The psychotic and deeply traumatised figures that trade the stories of their lives in the novel prey on the reader’s mind. The general sense of the uncanny is further increased by the cannibalistic horrors at the end of the novel. And yet, there are redeeming moments. Carey’s reference to Milton’s adaptation of the myths of Isis and Osiris is carefully chosen. The ritual killing of Chubb, like the ancient motif of sparagmos (the dismemberment and eating of the sacrificial victim to ensure new life), ordains hoaxer and fake as literary gods in the Australian pantheon, and adds to the country’s collective consciousness one more life-giving myth to underscore its cultural authenticity and self-reliance.

Comments powered by CComment