- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dressed for Deco

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A thirty-ish Peter O’Toole becoming an aged schoolmaster with powdered apple cheeks. I was a child when I saw the remake of Goodbye Mr Chips in 1970, but even then I could see that wrinkly make-up will never wash. More fascinating than the film was watching it in Walter Burley Griffin’s Capitol Theatre in Melbourne. The ceiling’s cunningly layered pleats of multi-faceted fittings were a million triangles softened in an illuminated cloud of pink and rose and yellow hues. It was my first knockout encounter with the style known as Art Deco.

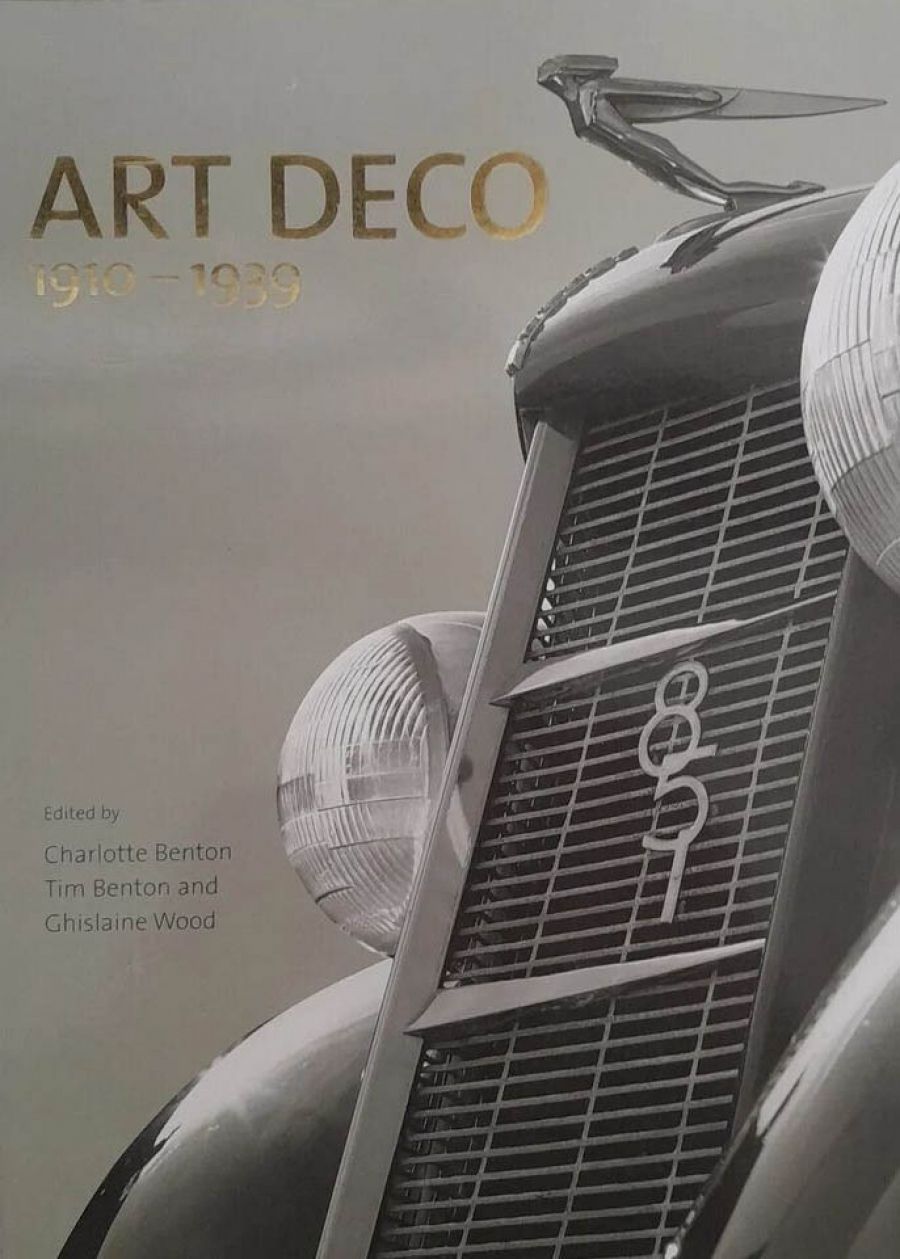

- Book 1 Title: Art Deco

- Book 1 Subtitle: 1910-1939

- Book 1 Biblio: V&A Publications, $120 hb, 464 pp,

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In the antipodean chapter of the book that accompanies the exhibition, Christopher Menz, of the National Gallery of Victoria, reproduces a picture of the Capitol’s interior (built in 1924) and cites Robin Boyd: ‘The best cinema that was ever built or is ever likely to be built.’ The thrill, of course, was that, for the price of a movie ticket, one could enter into a fashionable act of commerce. But we no longer find cinema-going – or air travel or department store shopping – glamorous. Certainly, we no longer dress up for it.

The editor’s note in the introduction that ‘Art Deco’ was not recognised as a style label until 1966, with the publication of Bevis Hillier’s Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. Deco was born and became a craze without ever having a name. John Pile’s ‘Art Deco’ Dictionary of 20th Century Design says that ‘the Modernists denigrated the style as Modernistic, putting a modern surface on things without any of Modernism’s depths’. That’s a lot of protesting moderns there. The book at hand notes that as late as 1984 a critic was writing doubtfully: ‘The critical re-evaluation of which Art Deco today is the object cannot deny that it consists more of a taste than a style, and this is responsible for the slippery way it resists theoretical categorization.’ A taste rather than a style?

Deco’s emerging ubiquity was assimilationist, and its borrowing of sources too nimble for it to calcify into strictness. What Deco was had a lot to do with what it wasn’t. Design rather than art, it wasn’t utopian but futuristic, not radical but stylising. Where the Constructivists made the linear express energy, Deco lines were elegant decoration. Where the Primitives used African art to re-energise the nude, Deco’s Nile style produced ‘Cleopatra’ earrings and lurex jackets with sequinned Egyptian motifs. Deco was the play costume of an age newly electrified and mass transported.

It began in luxurious fashion, employing precious metals and woods; with the onset of the economically depressing 1930s, it embraced chrome and bakelite. When, in late 1922, by candlelight, Howard Carter peered into a dark Egyptian tomb and saw ‘everywhere the glint of gold’, he was lighting the fuse to what would become Tutmania, one of Deco’s great touchstones. When, in Flying Down to Rio (1933), Fred and Ginger, for the first time, danced across a cheerfully cheap and artificial set, they became exemplars of the moment’s style. Deco was simultaneously high style and demotic, taking in ballrooms and cigarette lighters.

Was Art Deco merely ‘Modernistic’? Did it simply substitute a dress code for a program? One may as defensibly argue that it was ahead of its time – not Modernist but already Post-Modern. As Art Deco: 1910–1939 demonstrates in its hundreds of pictures and the connecting skein of exegeses, Deco was the international face of its age. Not the faces of Dorothea Lange’s WPA farmers or August Sanders’s peasants, but the shining face of grace and luxe and leisure – that is to say, one kind of the best we can be. As someone once remarked about civilisation, even a veneer is an actual thing.

A fat and, yes, sumptuous example of scholarly focus and production values, the book includes endnotes for forty chapters, a bibliography, a name index, a subject index and an object list. But, in the end, as at the start, one could leaf through the book over and over just for the pictures of objets d’art deco.

In becoming familiar with its themes and motifs – frozen fountains, gazelles and leaping female nudes, Egyptian makeovers and chinoiserie, buildings that curve around the corner – we begin to form not only affection for the style’s jazziness, but also become armed to join the dots. The dots criss-cross the world: from Le Corbusier’s cowhide chaise longue to the Chrysler building. It connects Brancusi’s sculpture to Cassandre’s typography, Aztec revival to Josephine Baker’s banana skirt, and of course all those trains and boats and planes and cars. That’s when we begin to recognise everywhere the glint of Deco – how, for an odd instance, today’s upmarket toasters still manifest the DNA of Deco chic. And I have, myself, begun spotting here and there crouching tiger lilies and hidden dragonflies.

Comments powered by CComment