- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dream On

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A fascination with the kinds of abodes we humans inhabit, and dream about, is the central theme around which Mark Wakely has spun his wide-ranging observations, anecdotes and personal stories. The topic lends itself to as many possibilities as you wish to make it. In order to narrow the focus, the author could have gone several ways. One approach would have been to write for a specific audience, perhaps for people interested in building a home. Or the book could have become a memoir of observations and people around their favoured homes. The author has instead decided to present stories, facts and observations that seemed relevant to specific periods of life, from childhood to old age, even death (what kind of mausoleum would you like as your final resting place, baroque or minimalist?). Although a valid approach, the book’s form presents particular problems.

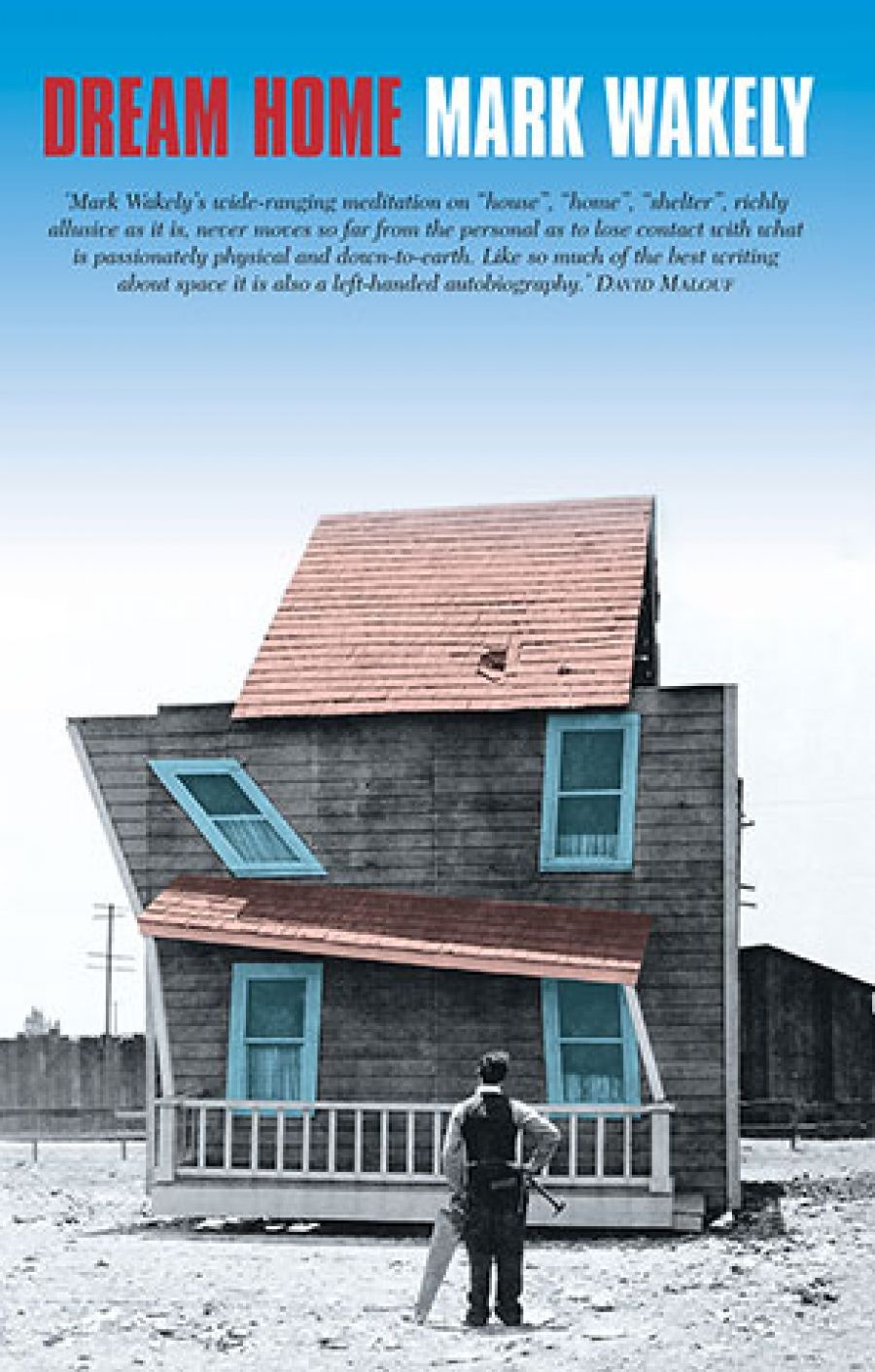

- Book 1 Title: Dream Home

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 236 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The book skips through a considerable range of facts and thoughts, touching on them lightly. At times, the array is so wide as to bewilder, and one wonders about the basis on which topics were selected. For example, why are five pages devoted to dolls’ houses? Do they have such a deep significance in forming our ideas on housing? In this early section, titled ‘Playing House’, the author draws a connection between experiences in childhood that lead to narrow and unimaginative approaches to house design in later life. If these childhood experiences are important to dull house design, we are not told why. It is almost as if the author was on the lookout for any relevant material to fill each period of life from childhood to death.

The author implies that creative construction with building blocks or Lego in childhood, without adult interference, helps to develop an imaginative approach to architecture in later life. To avoid stereotypical housing, we are told not to build things with our children:

Some parents, rather than allowing their children’s imagination to lead the design of the tree house, encourage their children to build what they already know: conspicuous, elaborate versions of the parental home ...

More evidence is needed that free play with building blocks is as influential to developing an innovative approach to architecture in later life, as the author implies. It is likely that many other factors play as strong a role, if not stronger.

Observations about dolls’ houses, Froebel’s blocks, plasticine and cubby houses take precedence over discovering deeper emotional and intellectual experiences that may become associated in children’s minds with houses. It would have been interesting to relate psychological theories to a passion for certain kinds of housing. Presenting a brief Freudian or other slant may have added another dimension to the topic.

In the section ‘What Shapes Our Domestic Expectations’, we are again shown glimmers of insight, though why these particular influences are selected we are not told. Martha Stewart is cited, along with a long description of the Hearst castle (if it is not an influence, why is so much space devoted to it here?), nostalgia for the past and dreams of utopia. It is when the author relates how his own ideas about ‘the perfect home’ were formed that the book comes into its own.

The topic on the architect as an artist (are they, or are they not?) and their differing philosophies to their profession yields fresh insight. It is fascinating to be shown the process through which people go to select an architect to build their dream home. Although at times obvious statements impede the flow of ideas (‘There’s more at stake when building an architect-designed house from the ground up, rather than redesigning the interior of an existing one as I did. Most likely it will cost more money’), new vistas on the architect-client relationship are opened up. We learn how a Californian couple engaged Australian architects to design their house, long-distance, and what made the resulting house so successful. Giving five years of your life to the process helps.

An in-depth view into the way architects go about designing their own homes gives important clues about the best way to select an architect. Making sure client and architect share a philosophy on living seems imperative; do not engage Richard Leplastrier to design your dream house unless you believe in a pared-down lifestyle. His own home:

sits beneath a high-pitched corrugated metal roof, with three-metre-deep, cantilevered overhangs. Inside the only furniture is a stool, a drafting table, and a couple of chairs the architect inherited from his mother. At night mattresses are unrolled for the five members of the family to sleep on. Clothes are filed away in boxes and vanish into cupboards that in turn seem to disappear into three or four walls.

If your dream is a house that will herald to the world your material success, Leplastrier is not your architect. But if your aim is to encourage conversation or to commune with yourself or nature, he would build you a home to achieve those aims.

Another enjoyable section of the book explores the joys and misery of apartment living, not only today but in history. We learn that apartment living has been with us since Roman times, when nineteen out of every twenty Roman households lived in a precursor of the modern apartment, called ‘insulae’.

I also liked the section on old age, and the whimsical view of dying and the final dream home we believe will be our resting place. There are valuable observations and ideas about incorporating elements of the dream home into houses where elderly people live, providing architects and those planning their homes for old age with helpful hints.

Comments powered by CComment