- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Broad-brush History

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a welcome addition to the historical literature about Indonesia. Aimed at new readers with limited or no knowledge of Indonesia, and written in an informal and accessible style, it makes an interesting contrast with the other well-known history in this field, Merle Ricklefs’s History of Modern Indonesia. When Ricklefs produced his second edition about ten years ago (he published a third expanded edition in 2001), the very existence of the Indonesian state was not as problematic as it now seems. Scholars could still talk without hesitation of a ‘history of Indonesia’. These days, the future of the country as a single state is more contested than at any time since the 1950s. Hence Brown’s subtitle, ‘The Unlikely Nation?’ He explains in the foreword that, since the idea of a united archipelago is so recent, ‘in a sense the book has been written backwards, using the Indonesian state and nation at the end of the twentieth century as its starting or defining point’.

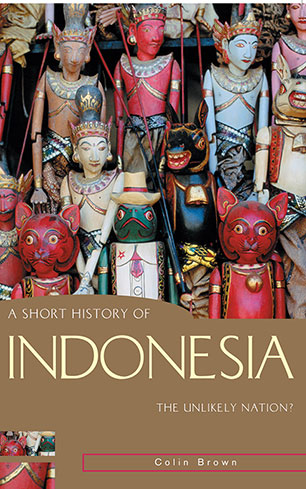

- Book 1 Title: A Short History Of Indonesia

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Unlikely Nation?

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 288pp, 1 86508 838 2

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The book starts off badly, with three of the most indistinct and uninformative maps my old eyes have ever peered at. But the narrative is attractively and fluently written, and in nine chapters Brown takes us through the geographical/physical environment, the rise of states, the age of commerce, economic decline, the rise of (the Dutch) empire, Indonesian nationalism and the Revolution, the first democratic period, the Sukarno and Suharto autocracies, and the current ‘reformasi’ period.

Brown indicates that, in some senses, Indonesia had its golden age during the history of the early kingdoms, recalling the legacy of the powerful trading state of Sriwijaya in Sumatra, and such superb monuments in Java as the huge temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Golden ages rarely look like that to the people of the time, and the limitations of the sources preclude much knowledge of less powerful social groups, but peasants, women and industrial workers do take the stage later in the narrative. Brown also makes regular efforts to cover the changing role of the Chinese community.

One persistent theme is the perception of Indonesians as having active agency in their own history. This emerges in Brown’s treatment of the so-called age of commerce, a term not used by Ricklefs. It may indeed be arguable that the worst long-term effect of Dutch colonialism (although this was not the only cause, as Brown points out) was not the political subjugation of the Indies, but rather the gradual separation of indigenous Indonesians from profitable international trade and commerce, in which they had been so skilful and successful in previous centuries. The dawning realisation by Dutch scholars in the 1930s that, despite appearances, Indonesians had not been passive culture-receivers but active participants in cultural and commercial exchanges along maritime trade routes was supported by later research. Brown mentions the startling fact that the people of Madagascar originated in late-prehistoric times from the Indonesian island of Kalimantan. More to the present point, detailed work on trade patterns during the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries has demonstrated the importance of Javanese, Buginese and Malay traders and sea captains.

Similarly, in describing the dynastic struggles of the Javanese kingdoms of the eighteenth century, Brown notes that the primary conflict was between the various claimants to the succession, while at that stage the Dutch were important only when ‘called upon to support one side or another’. He states, perhaps overstates, that the Dutch empire became established only by default, because of divisions and strife among Indonesians, and because other colonial powers (especially the British) had other fish to fry.

Brown recounts the progress and expansion of Dutch rule, the exploitative Cultivation System, which caused so much hardship, especially in Java, the Aceh War, and the fitful Dutch efforts to liberalise their régime. He treats in standard terms the rise of the nationalist movement, the Japanese occupation and the Revolution. He makes rather too much of the supposed ‘dilemma’ of the nationalists as to whether to cooperate with the Japanese. For almost all, the ruthlessness of the Japanese provided little choice. Moving to the Revolution, he tells the story of divisions among the nationalists, Dutch intransigence and the agonisingly slow, but eventually successful, mediation through the United Nations. He makes the point that the experience of the Revolution strongly influenced military attitudes (mostly negative) towards politics and towards civilians for years to come.

From 1945 onwards, Brown is on very familiar ground, having already covered this period in his earlier book about modern Indonesia, co-written with Robert Cribb: Modern Indonesia: A History since 1945 (1995). The unusual feature of Brown’s approach is the inclusion of the Sukarno and Suharto periods in the one chapter, arguing that the points in common were more significant than the differences. But he notes the ‘performance legitimacy’ established by the Suharto era’s impressive levels of economic growth, including the appreciable decline in poverty levels. He describes the collapse of 1997–98 in standard terms, including the exchange rate and debt problems and the IMF’s role, but also emphasises the political factors, especially the market’s sudden loss of confidence in Suharto’s leadership. Finally, he concludes that the break-up of Indonesia ‘would be a human rights disaster for its citizens, because any such breakup would be unlikely to occur peacefully’. Though rather negative, this is an effective reply to those who would welcome the dissolution of the ‘Javanese empire’.

One of the more depressing conclusions to be reached from this book is the phenomenon of ‘ageing scholarship’. By this I mean that in his fascinating ‘bibliographic essay’ at the end of the main text Brown quotes a large number of still-authoritative sources about various aspects of Indonesian history, which were written in the 1970s, 1960s or even 1950s. Scholars such as Kahin, Wang Gung Wu, Anderson, Feith, Reid, Ricklefs and Legge are eminent by any standards, but one is tempted to wonder where the new scholars on Indonesia are, and where are the new scholarly accounts based on detailed innovative research. If every generation requires its own version of history, where will the new versions arise, the detailed studies that provide the raw material for broad-brush histories such as this one? Is this the only area of scholarship where so many old sources are quoted so often by so increasingly few?

However, we should not be too gloomy. New students of Indonesian history are well served by balanced, lucid and comprehensive accounts like this.

Comments powered by CComment