- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Three Sleuths

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If we are to believe Aristotle, or the Chicago neo-Aristotelians (R.S. Crane, Richard McKeown, et al.), or even bluff old Squire Henry Fielding, then plot is the mainstay of drama, as of the novel. This has often been held to be particularly so of detective fiction. On the other hand, Raymond Chandler was notoriously cavalier about the ‘what, who, and why’ of narrative causation, and Edmund Wilson famously asked, ‘Who cares who killed Roger Ackroyd?’

It would seem that voice and character (Peter Corris’s Cliff Hardy, Gary Disher’s Detective Inspector Hal Challis, Shane Maloney’s Murray Whelan, MP) are as important as plot, if not on occasion more so. Milieu is crucial: think of Hardy’s Sydney, Peter Temple’s Melbourne, Carl Hiassen’s Florida, Elmore Leonard’s Detroit and Miami. Plot Rules, OK? Not! Voice is everything. Here’s quintessential Corris:

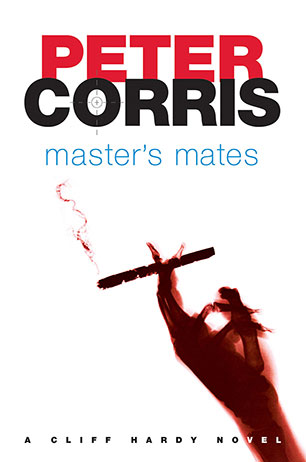

- Book 1 Title: Master's Mates

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $19.95 pb, 232 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

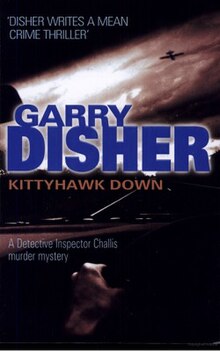

- Book 2 Title: Kittyhawk Down

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $19.95 pb, 275 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Something Fishy

- Book 3 Biblio: Text, $28 pb, 242 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

I hauled him up and dragged him into the kitchen. His head bounced off the doorjamb but just hard enough to trigger some adrenaline, not to knock him out. I placed him so that his head hung over the sink. The first retch started around his ankles and shook him like a dog coming out of water. He vomited hard, drew in a laboured wheezing breath and did it again. And a third time. The kitchen smelled as if I’d dropped a bottle of whisky on the tiled floor, a thing I’d never do. I put a wet tea towel in his twitching hand.

Toujours la politesse. Here’s a different kettle of stinking fish:

A lifetime of criminal intent had taught [Matthew Patrick] Moran the art of being a moving target. Born into a notorious crime family, he started carrying a gun as a teenager. And, in survival mode, associates said he would have been armed when taking his children to the Auskick clinic, even though he would not have attracted a second glance – just another Saturday morning at the footy with the kids … Despite all the bloodletting, Wendy Peirce is still shocked at the way Moran and Barbaro were killed. ‘It’s a dirty thing to do in front of all those kids,’ she said.

Actually, that’s from a press report on Melbourne’s recent ‘underworld gang war’. Corris writes better, but I know whom my money would be on if Hardy went up against Moran.

Despite ‘lifetimes of criminal intent’, there is an unavoidable impression that crime fiction is really concerned with anything but crime, as if the hard-boiled authors were displaced school teachers, social workers or university history lecturers. Z Cars was thinly veiled social meliorism; George P. Pelecanos is as much concerned with ‘pop’ music as he is with the plight of Washington’s black underclass; James Lee Burke is really interested in the psyche of the South; Lawrence Block, among others, is obsessed with alcoholism; Peter Temple is passionate about race horses and the authentic, pre-yuppy Melbourne; Michael Dibdin and his Aurelio Zen cannot resist writing about mother and bureaucracy; Carl Hiassen, in his journalism as in his crime fiction, is a passionate opponent of the depredations of developers, in Florida; Gabrielle Lord is deeply concerned about prostitution and kiddie-porn.

In this respect, David Marr may have been looking in the wrong direction when he reprimanded (if that is not too strong a word) Australian writers, in his Colin Simpson Memorial Lecture to the Australian Society of Authors (reprinted in The Australian Author, April 2003), for failing to represent or engage with major contemporary social concerns such as the Tampa affair, children in custody and the whole litany of disgraceful, selfish, xenophobic behaviour of the Howard government. While the reflections of crime writers on these matters may not be sufficiently extended or serious for Marr or anyone else, the three writers under review do advert to them. True to much detective fiction – not Mickey Spillane or Andrew Vachs, I admit – our three protagonists and their allies are old-fashioned liberals. Shane Maloney observes of Kennett-era politics and the ‘Coastal Management Advisory Panel’ (‘an arid source of diversion’):

A couple of meetings like this, and the real agenda will emerge. The privatisation of public assets along the coast. Camping grounds, piers, lighthouses, they’ll all be flogged to commercial operators, turned into theme parks, resort hotels and pay-per-view whale watching towers.

Like Corris and Maloney and any parent, Disher is concerned with kids and drugs, but also with detention camps.

The Chamber of Commerce welcomed a shot of federal money and renewed life for the worthless, empty buildings on the piece of marshland beside a mangrove swamp on Westernport Bay. As far as Ellen could see, the detention centre had provided only half a dozen jobs for the locals, lined the pockets of the American corrections company that operated it, and stirred up the local bigots. It had brought no joy to anyone.

Good old Cliff Hardy, in his twenty-sixth appearance, is an unreconstructed sentimental lefty, and none the worse for that. ‘It was September, two weeks after the media blitz on the anniversary of the attack on the twin towers and the story was still running, although there was a weird segue to the threat posed by Iraq to the “freedom loving people” of the world.’ Corris gives us crooks in all levels of society, police corruption in New South Wales, and enough venal lawyers to please even Evan Whitton.

Truth is, detective fiction may be generically conservative in a sentimental kind of way. As Maloney’s Murray Whelan puts it:

Hemmed by inviolable forest, Lorne did not have room for lateral expansion. So, year by year, the old houses with their wide verandahs, vegetable patches and couch-grass yards were giving way to low-rise cluster housing and sandstone mansions with garage access and touch-pad security. But not our place, thank Christ.

On Maloney’s account, New Year’s Eve in Lorne sounds as enticing as the same occasion on Bondi Beach. Cliff Hardy wouldn’t be caught dead at either. He’d be in his office in St Peter’s Lane, Darlinghurst (where Phil Noyce and others brought the Filmmakers’ Co-operative into the world in the 1960s), still failing to cope with computers, or in the Toxteth pub in Glebe, losing at pool and consorting with the shade of Dick Hall, or by the water in Balmain, or at home in Glebe, listening to Robin Williams’s ‘Science Show’ or Phillip Adams’s ‘Late Night Live’ on Radio National (he does both in Master’s Mates). You can’t get much more of an unreconstructed lefty than that. He even drives an old Falcon that lacks an automatic choke.

Detective plots can, if their begetters be insufficiently severe, choke themselves. Too many subplots can spoil the broth, as is evident in Kittyhawk Down, which is laxly rococo in comparison with Corris’s austere classicism. Then there is the old Dickens problem: not the ‘What to do with Jo [in Bleak House]? KILL HIM!’ problem, but the problem of coincidence, which may be as much of a crime as murder. Garry Disher writes: ‘Challis stared past them, staring into space, thinking it through. Coincidences did happen in murder inquiries, and so did things that were hard to credit, but he knew enough always to search for the simple answer, the most likely answer, first.’

But life, to paraphrase Henry James, is all confusion, while fiction ought to draw an exquisite circle around it. Coincidence is a more heinous crime in fictional detection than it is in real life. Maloney, particularly culpable in this respect, brings at least four various subplots and a case of mistaken identity together at New Year’s Eve in Lorne. Corris is not guilty so much of coincidence as of a hoary cliff-hanger or, given his hero’s given name, a Cliff-hanger. Jokes aside, it is good to see Corris back at the top of his form. Perhaps Hardy’s sojourn in New Caledonia on handsome expenses rejuvenated both gumshoe and his creator.

Comments powered by CComment