- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Oh Dennis!

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Oh Dennis!

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Oh Dennis, Dennis! For four decades, we’ve had to forgive your indiscretions and blemishes. We’ve done so willingly, because you were not only the fast bowler of a generation, but of that generation’s milestones. For many Australians, their national cricket team of the Lillee, Chappell, Marsh era was as important a cultural statement as the Beatles to the English in the 1960s. The stovepipe creams, the body-shirts, the massive crops of hair and the noses thumbed at the old Establishment, English and local, either drove or represented significant change in Australia. Lillee, ultra-competitive and irreverent (he said gidday to the Queen and asked for her autograph), stood at the forefront of all this. So we forgave him for the aluminium bat, for betting on England, for kicking Javed Miandad, for pulling out of a tour of England to help establish World Series Cricket – for so many things. And here we are again in 2003, still having to forgive him.

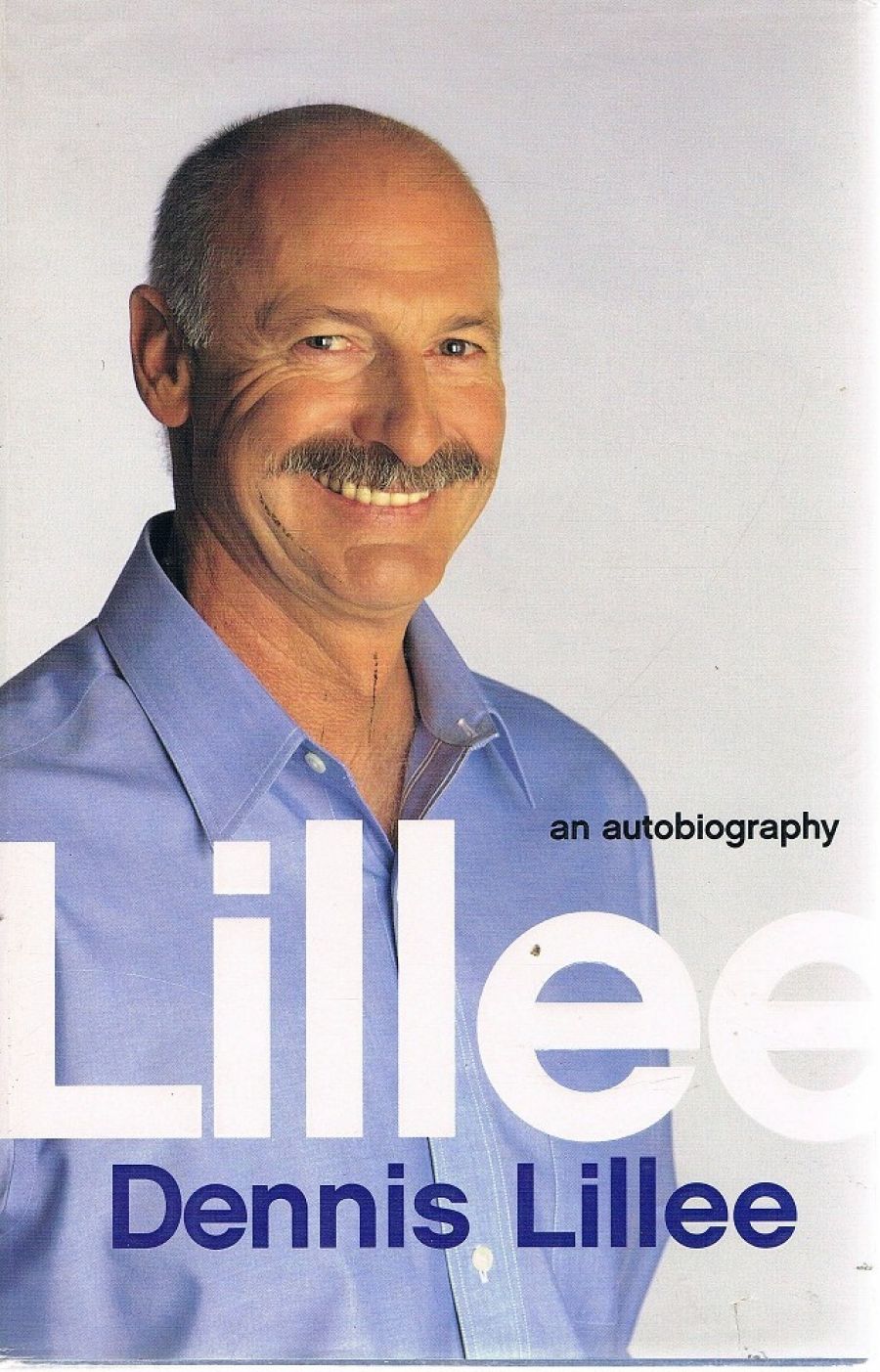

- Book 1 Title: Lillee

- Book 1 Subtitle: An autobiography

- Book 1 Biblio: Hodder, $49.95hb, 343pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This book is full of absolute howlers that do no credit to its ghost writer or editor. Jeff Dyson, not John, gets out in the second innings of a Test match against India. (No doubt J.D. will take the opportunity to re-introduce himself to D.K.L. the first chance he gets.) G.D. McKenzie, the great and much-loved Garth, receives a tennis ball while bathing, not batting, against Lillee in a county match in England – and not in Bath but in Leicester. Brian Davison, the hard-nosed, Camel-smoking Rhodesian who came out to captain Tasmania, is Brian Davidson. His former wife Caroline, the talented ABC sports broadcaster, is Carolyn. And Richard Soule, the stout, bullet-headed wicketkeeper from Mowbray, whose life’s ambition was fulfilled when he held a catch off his hero in Lillee’s first game for Tasmania, becomes Richard Souel. And on it goes.

Lillee the bowler would not have forgiven himself such technical errors. He grimaced over half-volleys and castigated himself when a ball drifted, as the commentators say, down leg-side. But as an autobiographer, he has served up so many wides, long-hops and rank full tosses that it’s a bit hard to take the rest of the book seriously. This is unfortunate. Because of Lillee’s place not just in Australian sport but as a player in the huge cultural shift of the 1970s, what he has to say about his early life and the things that shaped him are worth recording – but in better ways than this. Like so many Australians, his childhood was a mix of endless summer days, hard yakka helping a none-too-wealthy family and a rapid rise once his talent was noticed. It’s the story we egalitarian Aussies love to hear about ourselves.

Once he became famous, Lillee then became this road map through all our lives. I remember sitting in the old Bob Stand watching this mass of arms and legs running into bowl at the SCG during one of his first Tests. I was there when he came out to bowl in pain against Pakistan, his mere presence so frightening to the tourists that they imploded against Max Walker. For every Lillee event, there is a link to some-thing in my life, which is doubtless the case for thousands of Australians.

By the time he retired, in the same Test as Greg Chappell and Rodney Marsh, at the SCG at the end of Pakistan’s 1983–84 tour, I had become a sports writer. The chance to interview the trio on that precious day remains a highlight of what I occasionally delude myself is a career. The chance to read this autobiography is less so. Much of it sounds as though it has been transcribed straight from the cassette recorder. That’s okay – not everyone can be Neville Cardus, especially a bank teller from Perth who could also bowl fast — but it does make for a bit of a ramble.

There’s an obligatory chapter on Doug Walter. You couldn’t go wrong with a whole volume on that bloke. None of the stories about Dungog’s most famous son is new, but, from Lillee’s perspective, they gain new life.

There’s some good stuff on why Sunil Gavaskar can’t be ranked among Lillee’s list of the greats. The little Indian scored runs all over the place, even against the West Indians in the West Indies, but never as assuredly against Lillee. The Australian rates him as a fair batsman only. Rather, he plumps for Gavaskar’s brother-in-law, GundappaViswanath. Who could argue with him?

However, there are these incessant mistakes to contend with. Wasn’t it Gary Player, not Jack Nicklaus, who said that the more he practised, the luckier he got?

Still, I persevered, wincing at the howlers as if struck by a Lillee bouncer, but keeping my head down. It was, I realised, as much a personal journey as accompanying Lillee through his colourful and occasionally incandescent life, and I was able to enjoy it for that.

So Den, just as we always did when you were at your zenith – the great fast bowler, the champion of a generation that had discovered that we no longer had to tug the forelock to Mother England or old blokes in ties and suits – you’re forgiven. But if I were you (and how many times in my younger years I wished I could have been), I’d be making a phone call or two to the amanuensis and his editor and indulging in a little bit of old-fashioned, red-hot Australian sledging.

Comments powered by CComment