- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Exilic Colour

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Readers who share Helen Nickas’s view that Antigone Kefala’s fiction forms ‘a continuous narrative which depicts and explores the various stages of an exilic journey’ may be pleased to find more instalments in her fourth book of fiction, Summer Visit. The first of the three novellas is an account of an unsatisfying marriage, told with a controlled detachment that makes its title, ‘Intimacy’, seem ironic. In contrast, the third, ‘Conversations with Mother’, contains a series of elegiac apostrophes of the deceased; the connections with Braila and other congruities with a figure familiar from previous writings again encourage an assumption of autobiography.

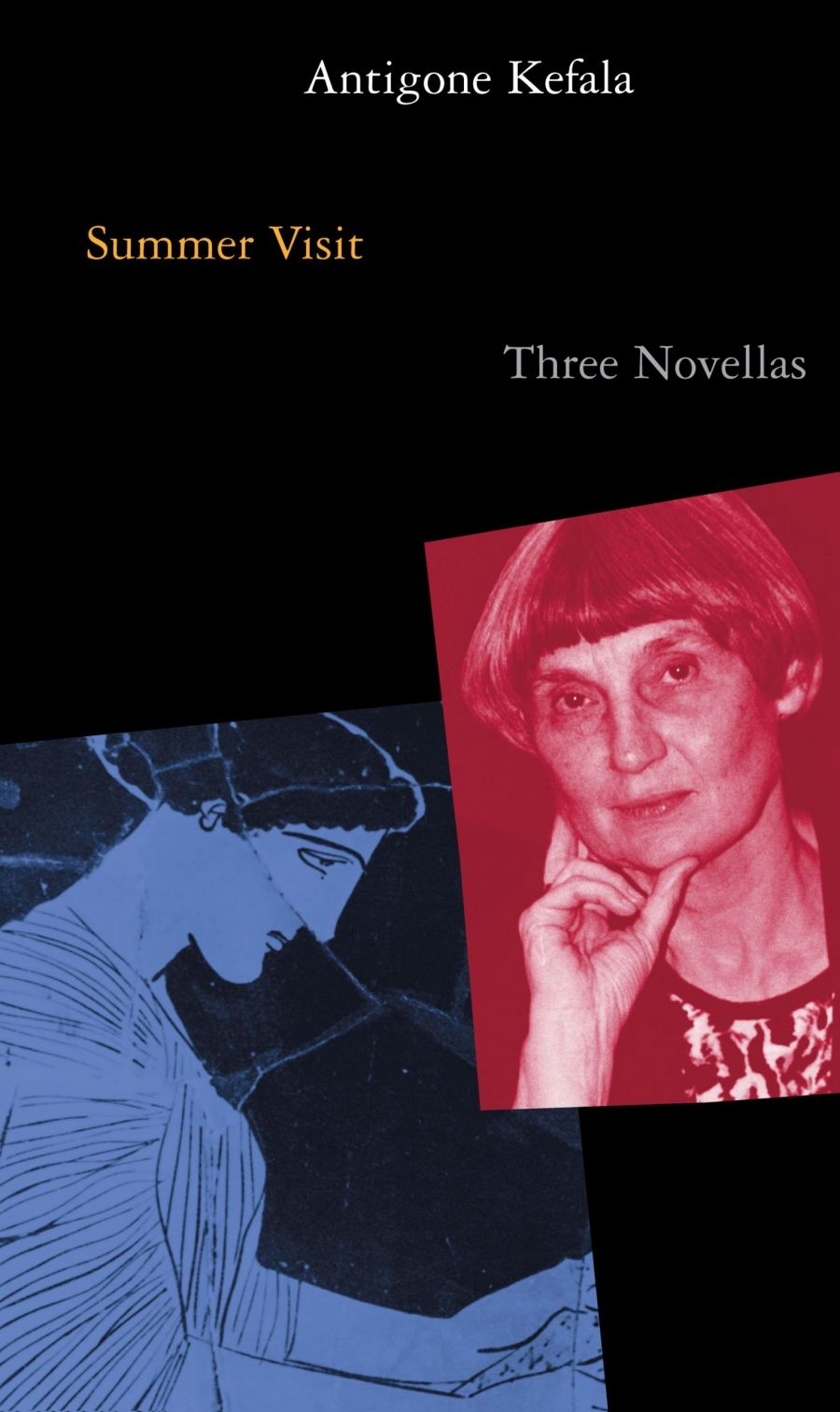

- Book 1 Title: Summer Visit

- Book 1 Subtitle: Three novellas

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo. $20 pb, 120 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: The Island/L’île/To Nisi

- Book 2 Biblio: Owl Publishing, $24.95 pb, 181 pp

However, it is the middle, title story, ‘Summer Visit’, that will provide most sustenance for followers of Kefala’s repeated engagement with issues in her diasporic identity. The summer visit is to Greece, the briefest of Kefala’s stops en route to Sydney, and it provides opportunities for laying ghosts. She revisits the Piraeus orphanage that was the whole family’s cramped refuge after fleeing Romania. A relative’s photograph album prompts painful memories of a brother’s psychological disorder that disabled an entire family. The narrator further realises, as do many diaspora pilgrims to Greece, that: ‘Every time I come here, it is as if I enter, rediscover a physical ancestral line ... something that feels infinitely familiar. It is as if one can see where one has come from and where one is going.’ The last clause is particularly significant, for the summer visit ends in alienation. In both parts of the novella, the European sophisticate of the antipodes is sidelined as an uninteresting interloper in the self-absorbed worlds of boorish coevals and cosmopolitan Athenian yuppies alike.

In between, the narrator grows into the role of a privileged tourist. She lapses into supplying a kind of travel journal, where most of the standard gamut of ‘postcards’ is rehearsed: balcony views of the sea; the main street of a Greek seaside town; al fresco cinema; faces in a coffee shop – and not just those of the patrons: ‘the cups as if Cycladic sculptures, the handles delicate earlobes’. She duly records the locals’ literal belief in personified death and other arcane folkways ranging from ‘rembetika’ (complete with tourist spelling) and the accompanying dance (‘a swirling, static turning in the beat, to the clapping of hands’) to the relentless attention-seeking on the part of males in this theatrically patriarchal society. And, although keen to distance itself at the outset from the tendency of travelogues to have a ‘patina of classical sentimentality filtering their view of the moderns’, her narrative, too, has the ‘images in the museums constantly reinforcing the people in the streets, their heads, profiles, attitudes, their bodies’. What rescues Kefala’s holiday journal from banality is the elegance of her descriptions and the acuity of her vision, especially her eye for colour.

An earlier skirmish with Cavafy’s ‘Windows’ seems to set the stage for a finale along the lines of his ‘Return from Greece’. In the event, the return flight to Sydney is screening The Man from Snowy River II, and the narrative prudently passes over one more opportunity for another mini-film review. The story ends in poignant contemplation of a kindred object, ‘the static wing of the plane, alone in the dark universe’.

The Island depicts the New Zealand stage of Kefala’s ‘exilic journey’ and revolves around the first love of the heroine Melina. This is framed in such an ‘emptying of impressions, people, landscapes, worries, complaints, rearrangements of the past’, as ‘Conversations with Mother’ reflexively confesses, that it was perhaps inevitable that the two books reviewed here would intersect. This occurs most noticeably in a repeated anecdote about giant hens hatching suitcases and aged refugee women counting them each morning.

The Island was reviewed on its first publication in 1984, so what follows will focus on the novelty of the latest (third) edition: a juxtaposition of the original English text with two translations, one French (by Marie Gaulis), the other Greek (by Helen Nickas).

The main aims of this edition are to celebrate both multilingualism and translation, for all its notorious infidelity, and to make a virtue, for once, of the unashamed visibility of translation. All this, ‘unencumbered by commercial considerations’, for which all praise the Australia Council and the National Council for the Centenary of Federation, not to mention the deep pockets of a crusading publisher – for this is Owl Publishing’s third publication of Kefala in facing translation in the series ‘Writing the Greek Diaspora’.

Trilinguals inclined to respond to the translators’ red rag with pedantry had better note in advance that even the final phrase of the novella diverges markedly in the three texts, and that both translations come with the imprimatur of a polyglot author who might have rewritten the novella herself in both Greek and French, and who had a hand in elaborating the final form of both translations.

I decided to heed the prefatory advice to slalom across the pages, savouring the linguistic jeux de miroirs and not worry too much, for once, about occasional suspicions of flaws in the glass – even when the French opts for a lovelorn madman and the Greek for a lovelorn madwoman in rendering the song ‘I’m a Fool to Want You’.

Nickas’s introduction, though, provokes debate at a number of points. For a start, the claim that ‘the multilingual reader will be getting three readings out of the same text, simultaneously’ (my emphasis) is profoundly problematic. Then the preoccupation of this novella with issues of language is arguably overstated. Nickas’s reading is consciously at variance here with the emphasis of previous commentary on The Island and may reflect her own legitimate predilections as a language teacher and an adult immigrant to Australia.

Another issue arises in the claim that the ‘un-Englishness’ of Kefala’s language ‘faithfully expresses the “otherness” of her characters’ and that this requires a form of Greek other than standard Athenian in the translation to capture ‘that very foreignness’. As a woman ‘placed outside a so-called mainstream of [Greek] linguistic activity’, the translator claims to be equipped to supply this. In my perception, the most distinctive feature of the Greek translation is a certain slackness of syntax, to the point of occasionally unravelling (as at the end of paragraph three on page 71); this eludes me in the English. (My French must be too rusty to reveal how the same endeavour is realised in that translation.)

It must also be noted that both translations have a connection with university theses on Greek–Australian literature. The links between the publishers of these two works and Australian universities also prompt consideration of the role of educational institutions in canon-formation. But for present purposes, the fact that one of the theses on Kefala was written at the University of Geneva by a French-Swiss neohellenist reminds us of the global context of the Australian branch of Greek diaspora literature. This encourages hope that the publisher’s aim ‘to create an audience for multilingual books’ will prove to be more visionary in global perspective than quixotic in local terms.

Comments powered by CComment