- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Colliding Brazils

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian writer Peter Robb has once again written a whole, complex, foreign society into our comprehension. This time it is Brazil, its myriad worlds of experience, its cruelly stolid immobility and exhilarating changefulness, its very incoherence, somehow made accessible to our understanding. In 1996 Robb’s Midnight in Sicily was published to international acclaim. He had set himself the task like the one the mythical, doomed Cola Pesce had been commanded to achieve: to dive into the sea of the past; ‘to explore things once half glimpsed and half imagined’; and to discover ‘what was holding up Sicily’. And he succeeded magnificently.

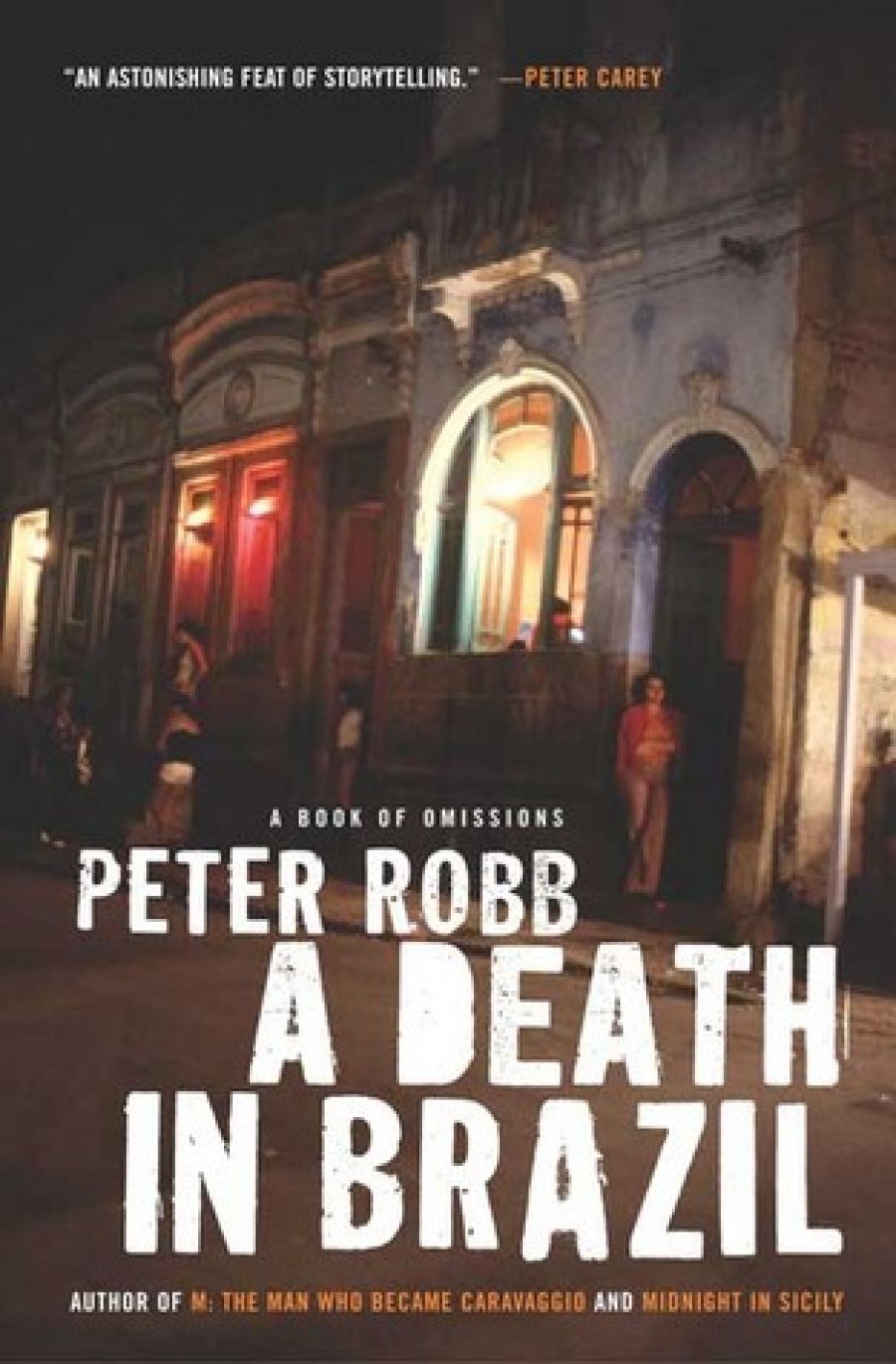

- Book 1 Title: A Death in Brazil

- Book 1 Subtitle: A book of omissions

- Book 1 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $45 hb, 372 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Robb is less explicit about his tasks as he sets out with us in A Death in Brazil, but it soon becomes clear that they are ambitiously the same. He wants to reveal what is holding up Brazil, to chart the flows of power from colonial times to the present, eddying from patrimonial backlands to the institutions of the modern federal republic, dammed and diverted by smart operators and presidents, coursing through the veins even of rebels. In Midnight, he set out to show how and why things go on changing, and why they stay the same, focusing everything in the closing pages around the amazing Andreotti mafia trial in Palermo.

In the last chapter of A Death in Brazil, we see what Robb has been doing all along – trying that plus ça change plus ça la même chose hypothesis. He concludes two stories that he has been unfolding throughout the book. The one, the story of Luís Inácio ‘Lula’ Da Silva, the son of a rural labourer, former shoeshine boy, union leader and co-founder of a very new sort of party of the left, the Workers’ Party, who is elected president of Brazil in 2002 – ça change. The other, the story of impeached President Fernando Collor, playboy scion of a rich family accustomed to mafia-style subversion of public life, and his stupendously corrupt henchman, P.C. Farias. That, too, comes to an end in 2002 with the return of Collor to state politics a decade after the impeachment, and then the final in a series of acquittals that leave surviving members of P.C.’s gang (P.C. had been murdered) unpunished, free to lead the high life to which they are accustomed – ça la même chose.

So this is a political book, but so profoundly dedicated to revealing what is holding up Brazil that politics is only part of it. It is also a book about race relations, the legacies of slavery, sexual mores, street kids, food and failed alternative Brazils. As Robb takes us exploring change and no change in Brazilian politics, we are introduced not only to the big figures in political society but to writers who have powerfully shaped Brazilians’ conceptions of themselves over the last century and a half – three in particular: Gilberto Freyre, Euclides da Cunha and Machado de Assis. Freyre kept rewriting his evocative The Masters and the Slaves over forty years from its first publication in 1933, re-creating the Northeastern sugar plantations in which, he argued, a vital, distinctive Brazilian civilisation had been born of the miscegenation of African, Indian and Portuguese. Freyre was arguing against the positivist, evolutionist modernisers who feared the Northeasterners of plantation and backlands as regressive savages, doomed by the march of white European Progress, but capable, nonetheless, of holding Brazil back.

Euclides da Cunha was one of those modernisers, but with a sense of the paradoxes and tragedies of modernity as strong and vividly expressed, as Robb points out, as Joseph Conrad’s in Heart of Darkness and Nostromo. In 1902 (the same year as Heart of Darkness) da Cunha published his monumental account of the destruction of the city of Canudos, the redoubt of monarchist, folk Catholic backlanders who had poured in from the lands ruled by the coronéis (the colonels) to lead a better life around the mystical restorer of derelict churches and fighter for justice, Antonio Conselheiro. The novelist Machado de Assis, enormously popular among Rio’s bourgeoisie in the later nineteenth century (much of his work appeared in women’s magazines) figures in Robb’s book in the same ways as the other two writers. Robb re-presents each writer’s foregrounded segment of Brazil (in de Assis’s case, Rio’s bourgeoisie) and locates it against its other – Rio bourgeois versus North-eastern backlander, plantation Pernambucano versus industrial Paulista. So, in deft résumés of writers whose own representations still shape Brazilian identities and imagined communities, we begin to see Brazil defined around its fault lines. Then the three writers figure in Robbs text in another way: they become dramatis personae, portraits among the many that Robb uses to detail his Brazil.

The portraits include names known to educated Brazilians and Brazil watchers: the three writers, recent presidents, the historical challengers such as Antonio Conselheiro, Zumbí and Dom Helder Câmara, and the infamous rogues of the Brazil that stays the same. But the gallery also includes ordinary Brazilians whom we know only because Robb introduces them to us: Adelmo, who, desperate for money, held a knife to Robb’s throat and, even more desperate for someone who would talk to him with respect and attention, let him go; and, above all, the late Vavá, Robb’s friend in Recife, whom we meet in his bar and eatery in Chapter Two and learn more about in succeeding chapters, until the announcement of his death in the final chapter. Each of these, and many another, add something to the whole. But what is this whole that Robb so ambitiously seeks to present? It is certainly not the sort of whole Brazil we might have expected from an old social science: a society whole and coherent in its class structure, or its institutional matrix, or its place in the world system. It is not a Brazil knit together by a national culture and expressed in a shared national character. Rather, Robb’s whole Brazil comes into focus when he shows us the Brazil that stays the same colliding with the Brazils of the challengers, when he demonstrates private troubles linked to public issues, when he helps us to see rival imagined Brazils jostle in public space, and when, sometimes in an incident of escape, sometimes in a longue durée story, we glimpse the confluence of powers that define a national society.

I don’t think Robb regards himself as a social scientist. But in my view, as a sociologist and an old Brazil hand, Robb’s portrait of a whole Brazil is a great social science achievement. So how has this cosmopolitan writer and man of letters done it? The short answer, I think, is: in the writing. The good science starts with Robb’s excellent ethnography and careful historical research, but, in the end, it is realised in the artistry, even the artifice, of his book. We are able to glimpse defining historical continuities and change by accretion, because Robb makes them happen in the text. In one chapter, details about the absolute newness of Lula emerge the more clearly against the backdrop of the history of slavery. A heritage of struggle against slavery, which Lula acknowledges as part of his identity, is established by the telling of the story of the hundred-year history of the runaway slave republic of Palmares. Then there are details about the Inquistion in Brazil, the colonial Church and the Tupí Indians. Abruptly, Robb takes us forward in time to Vavá’s bar and eatery, and a discussion of salt cod. It sounds bitsy, but there is a wonderful fugal density in this sort of chapter structure. And chapter after chapter, as historical flashbacks judder against the resumed narrative of Collor and P.C., and as details of private lives are juxtaposed with news of the political economy and tales of Robb’s personal experiences, we approach a comprehension of Brazil that is never spelled out, and can’t be, but is with us nonetheless.

Of course, despite the detail, there is much that is missing, just as there is in comparable works such as Joan Didion’s revelation of what holds up Miami, or, in a different medium, Robert Altman’s portrait of Los Angeles in Short Cuts. Paulistas will complain that their city of São Paulo, with its population about equal to Australia’s, is given short shrift in comparison to Recife, a world away in the Northeast. I might grumble that the Northeast cannot be understood unless Padre Cicero is put back in, that nuances of the Protestant Pentecostal explosion in Brazil should be further explored, that a wider range of Brazilian soapies be considered. But as the list grows, the grumbling appears more ridiculous. The communication of a whole society comprehended requires artful omission as well as commission. Robb is unerringly artful, even in his choice of subtitle: A Book of Omissions.

Comments powered by CComment