- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Surviving the Bearpit

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I must confess I picked up this celebrity autobiography, complete with embossed cover and a price suggestive of a huge print run, without anticipation. I could not have been more wrong. Mike Munro’s excoriating and frank account of his abused childhood and early years in journalism chronicles a survival story that is Dickensian in scope and impact. Like Dickens, Munro managed to overcome poverty, cruelty and emotional deprivation to reach the top of a demanding profession. Remarkably, considering his scarifying experiences as a child and adolescent, he fell in love and married a partner with whom he has created the kind of loving family life that he never knew as a child. But I am jumping ahead.

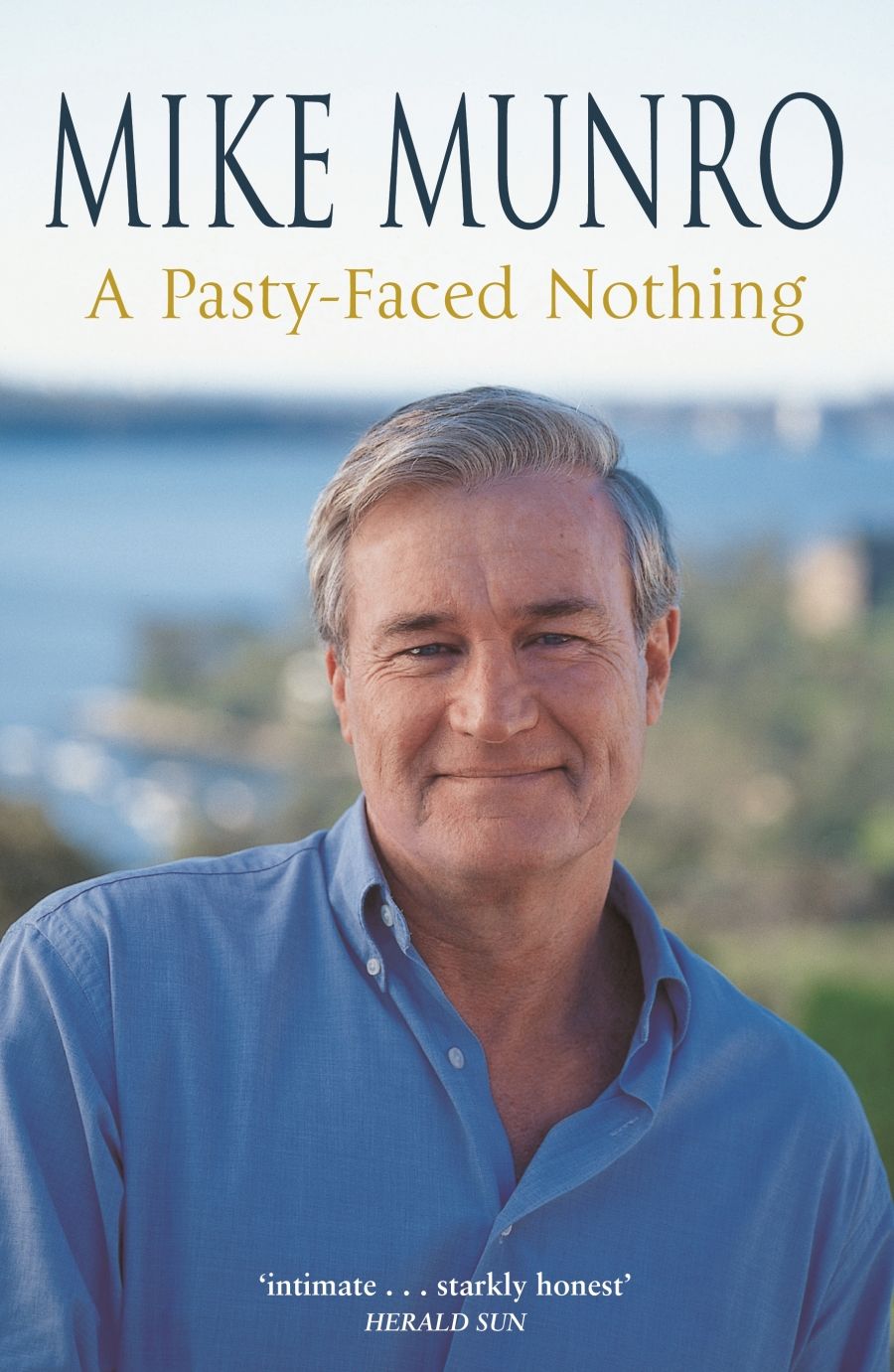

- Book 1 Title: A Pasty-faced Nothing

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $39.95 hb, 373 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It would be wrong to suggest that Michael (he was not Mike until Channel 9 decided that it was more suited to his hard-hitting television persona) grew up without love. He begins his autobiography with the birth of his mother, not himself. Beryl Jean Stannard was a loving mother, when she was sober. She put her life on a disastrous course when she picked the wrong bloke, a charming Irish-Australian conman, Raymond Michael (‘Mick’) Munro, who drank, gambled, womanised and stole from his friends to support his drinking and racetrack addictions – a dangerous trifecta of nags, trots and the dogs. In 1957, with a four-year-old son, Beryl fled the marriage and battled as a single mother in Sydney, with a variety of menial jobs.

Beryl began drinking secretly to escape the awfulness of her life. While drunk, she would beat her infant son, sometimes with an ironing cord or buckled belts. At the age of six, Michael worked out that the bottles hidden in the clothes basket were the cause of her mood swings. When she passed out, he would tip them down the toilet. This triggered more beltings. There was a period of relative stability while Beryl held down a job as a cook at a Catholic monastery, but some nights Michael would leave the house and hide in the grounds to avoid the beltings. Eventually, Beryl drank her way out of that job, and they moved from one ghastly rat-infested lodging to another.

When Michael was thirteen, Beryl scored a job in a liquor shop – not a good thing for an alcoholic. At least Michael became strong enough to resist some of the beatings. At these times, she would abuse her son, calling him ‘a pasty-faced nothing’, among other endearments. Somehow, even as a very young child, he knew this was the alcohol talking, not his much-loved mother. Yet he remained loyal, encouraged her to seek counselling for her alcoholism (which she would never acknowledge) and managed to develop into a resourceful lad – with a bent for ingenious practical jokes – who adopted some of his friends’ families as his own. Michael had to grow up fast, unable to share the realities of his crisis-ridden life even with his closest friends. I found the account of his childhood and teenage years not only gripping but deeply impressive. To call it a triumph of the human spirit is not hyperbole in this reviewer’s opinion.

Munro’s life picked up markedly when he managed to get a cadetship with the Sydney Daily Mirror in 1971 – and even more so when he fell in love with his future wife, Lea, of the ‘light brown hair and piercing green eyes’. ‘She was 15 going on 19. I was 19 going on 14.’ One of the great blessings of journalism, if clichés are avoided, is that it encourages short sentences in the active voice.

Munro developed a professional reputation for being a hard-nosed and enterprising chaser of stories, honed in the daily tabloid bearpit where there are no prizes for coming second. In autobiography, it is important to be able to tell stories against yourself. Munro obliges. I particularly liked one anecdote from not long after he started with 60 Minutes, in 1988. Perhaps luckily for him, Kerry Packer did not then own Channel 9. The story was about polo. Munro’s first question should have been: ‘Mr Packer, why polo?’ Instead, it came out: ‘Mr Polo, why Packer?’ Munro writes: ‘There was a moment’s silence before he calmly asked me: “Do they pay you much to do this sort of thing, son?”‘

In fact, reporters on 60 Minutes were paid quite a lot. This was the era when no story was too expensive to cover, no matter in what remote corner of the world. The programme’s four reporters spent almost the entire year globetrotting, serviced by a relay of field producers. It was exciting stuff, but exhausting and not good for family life, which was a priority for Munro. The tyro ‘foot-in-the-door’ reporter would stop at nothing, even running with the bulls at Pamplona – twice – once for a rehearsal, and once for the cameras. That was probably less dangerous than filming in the field with the IRA in Northern Ireland.

Inevitably, books like this recap ‘famous people I have interviewed’, as well as notable stories in war zones and of political crises. Munro is reasonably restrained in this tricky juggling of ego and derring-do. Sweet-talking an exclusive interview with the veteran actress and known reporter-eater Katharine Hepburn – she even asked him to lunch! – deserves the space he devotes to it.

Munro gives his side of some of the more controversial episodes in his career, including the notorious helicopter landing in March 1993, when he was with Michael Willesee’s A Current Affair. This was during a kidnap siege near Glen Innes, in north-eastern New South Wales. Three gunmen on a murderous rampage had kidnapped two small children as hostages and held them in a farmhouse. Willesee interviewed the children live on the programme. Munro was accused of landing dangerously close to the farmhouse against the wishes of police negotiators. Munro’s defence of his actions has more credibility than his involvement with the three hapless ‘dole bludger’ Paxton kids, victims of three generations of unemployment in their family, who were interviewed in 1996, when Ray Martin was fronting the programme. When the two Paxton brothers and their sister were offered jobs on a Hamil-ton Island resort, A Current Affair flew them to Queensland with Munro and a camera team. The Paxton brothers refused the jobs because they would have had to cut their long hair. Allegations of popular, tabloid-style exploitation remain difficult to refute.

Always a workaholic, Munro juggled his current affairs assignments as compère of This Is Your Life. When this book was published, his future with the Channel 9 network was uncertain. With Munro, you get the feeling that if he had to walk away from the circus of commercial television to spend more time with his wife and two children in their Palm Beach house, he wouldn’t shed too many tears.

Comments powered by CComment