- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: Abundant Pleasures

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Abundant Pleasures

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When he died in 1989, the artist Donald Friend left a double legacy. The first was his artistic output, as various, dazzling and charming as it was vigorously contested in terms of its ultimate quality. The second was an accumulation of forty-nine diaries commenced precociously at the age of fourteen, kept briefly for a year or two and then, from the war years on, written lovingly and obsessively for much of the rest of his life. Friend’s art as draughtsman and painter is widely held in public and private collections; the bulk of the surviving diaries were eventually acquired by the National Library of Australia. Profusely illustrated, these intimate personal records document a remarkable life while providing a detailed insight into one man’s struggle with the processes of making art. In their span, the diaries constitute an extraordinary individual record of twentieth-century Australian experience in war and peace.

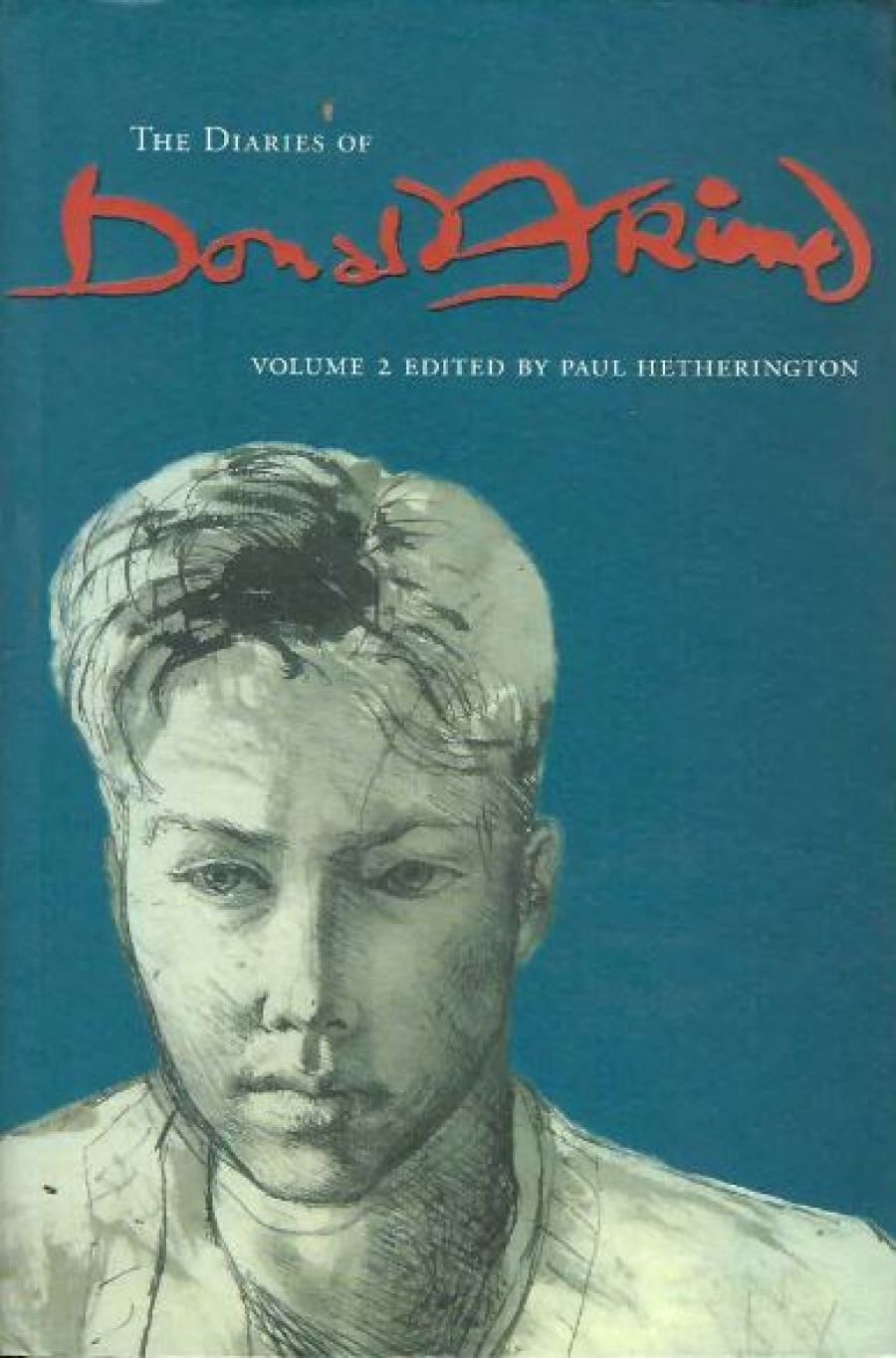

- Book 1 Title: The Diaries of Donald Friend

- Book 1 Subtitle: Volume 2

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $59.95 hb, 752pp, 0 642 10765 3

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In 2001 the National Library began the difficult task of bringing Friend’s diaries into a form in which they might reach beyond scholars and art historians to communicate with a general audience prepared to respond with compassionate interest to one man’s journey and to savour a vivid collective portrait of Australian life. That year, Anne Gray, the National Gallery’s Senior Curator of Australian Art, edited the first of a projected four volumes with a keen sense of the challenge she faced. Editing the diaries was never going to be easy. How to reduce to manageable proportions Friend’s millions of uneven words, his repetitions, trivia, moralising, carelessness, libellous candour and, sometimes, his obscurity? How to deliver the best of Friend in a form that preserves his essence and delivers a comprehensible text to a new audience coming fresh to material that requires a sense of context and cultural awareness of the period and its personalities? There is an inherent tension in the editing of intimate or private texts such as diaries and letters – material written in a particular and very personal context, but which must then be reshaped for a general audience.

Now, with the swift appearance of a second volume, a new editor wrestles afresh with the many challenges embedded in Friend’s rich literary legacy. Gray’s pioneering place has been taken by Paul Hetherington, a noted Australian poet who in his day job is the National Library’s own publisher. Other changes are evident: the Library has abandoned the awkward chunkiness of the first volume to produce a book that is more assured and handsome; Gray’s proposed periodisation of Friend’s material has been altered; and the footnotes disappear from the pages to sit in cumulated form as endnotes. Purists may object to this evidence of a publisher thinking on the job. There is a loss of physical and intellectual consistency, but, in the end, we may see that Friend himself has been better served; it is best to abandon regret and move on. In any case, the delights and pleasures of this new volume are abundant.

In his breezy cover blurb endorsement, David Marr invites a celebration of the irresistible company of Donald Friend. He observes a man who is vivid, funny, snotty, curious and shrewd, and who writes with a painter’s eye. The triumph of the diarist’s art is that we see it all: the friends and lovers, painters and painting, wartime Brisbane after dark, Sydney in the first chaotic years of peace, triumphs and brawls in the arts, raw beauty in the Torres Strait and dry bush comedy as Friend seeks to find domestic peace in the gold-mining village of Hill End in New South Wales. Historians of all colours will relish the accounts of the Archibald Prize controversy of 1943, the eruption of the Ern Malley hoax, Friend’s assignment as an official war artist, the experiments in living and the making of art that distinguished the Merioola and Hill End ventures in the postwar years. Readers of the human condition will respond to the impulse that drives all this, the questing, doubting figure of Donald Friend, often drunk, usually in love, who puts the pleasure, the comedy and the pain of his life onto the page.

Hetherington is a cool and thoughtful editor who brings a sensitive touch to Friend’s life and experience in the final years of the war and in the period of his early adjustment to civilian life. As a writer himself, schooled in criticism and in the poet’s art of distillation, Hetherington is especially attuned to the architecture of Friend’s prose, to the ways in which the diarist shapes his material to sustain a lively narrative. As a compassionate guide to a complex personality, Hetherington is also alert to Friend’s personal evolution – the maturing self, the challenges to his romantic wishes and dreams, and the problems he faced in balancing the love for the sensual and the beautiful with his search for deeper satisfactions in intimate relationships and through the discipline of his art. At the heart of these diaries is a vulnerable, Friend, poignantly and powerfully in love with the young Colin Brown. As the jacket illustration suggests, the youth’s brief presence in Friend’s life inspired some of the artist’s finest drawings. For all the atmospherics of moonlight and waves crashing on deserted shores, the love affair and the vivid presence of Brown are tenderly evoked. Impressive too – and comprehensible – Is the account of the failure of love and of Friend’s courageous adjustment to loss.

In approaching the conjunction of love and art that stands as one of the central themes of this second volume, Hetherington deals with two large questions essential to any evaluation of Friend. As he must in the context of these latest diaries, the editor confronts the fact and the implications of Friend’s homosexuality in the socially conservative Australia of the day, when legal sanctions applied. More ambitiously, perhaps, he tackles the difficult task of appraising Friend’s art and of placing him more certainly in the Australian canon. In this last, not all will agree with what is a literary reading of the visual medium. But Hetherington offers here a spirited and overdue attempt to comprehend the essence of Friend’s achievement, in what the diaries show was the central discipline of his life.

Comments powered by CComment