- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: Hardy Times

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hardy Times

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

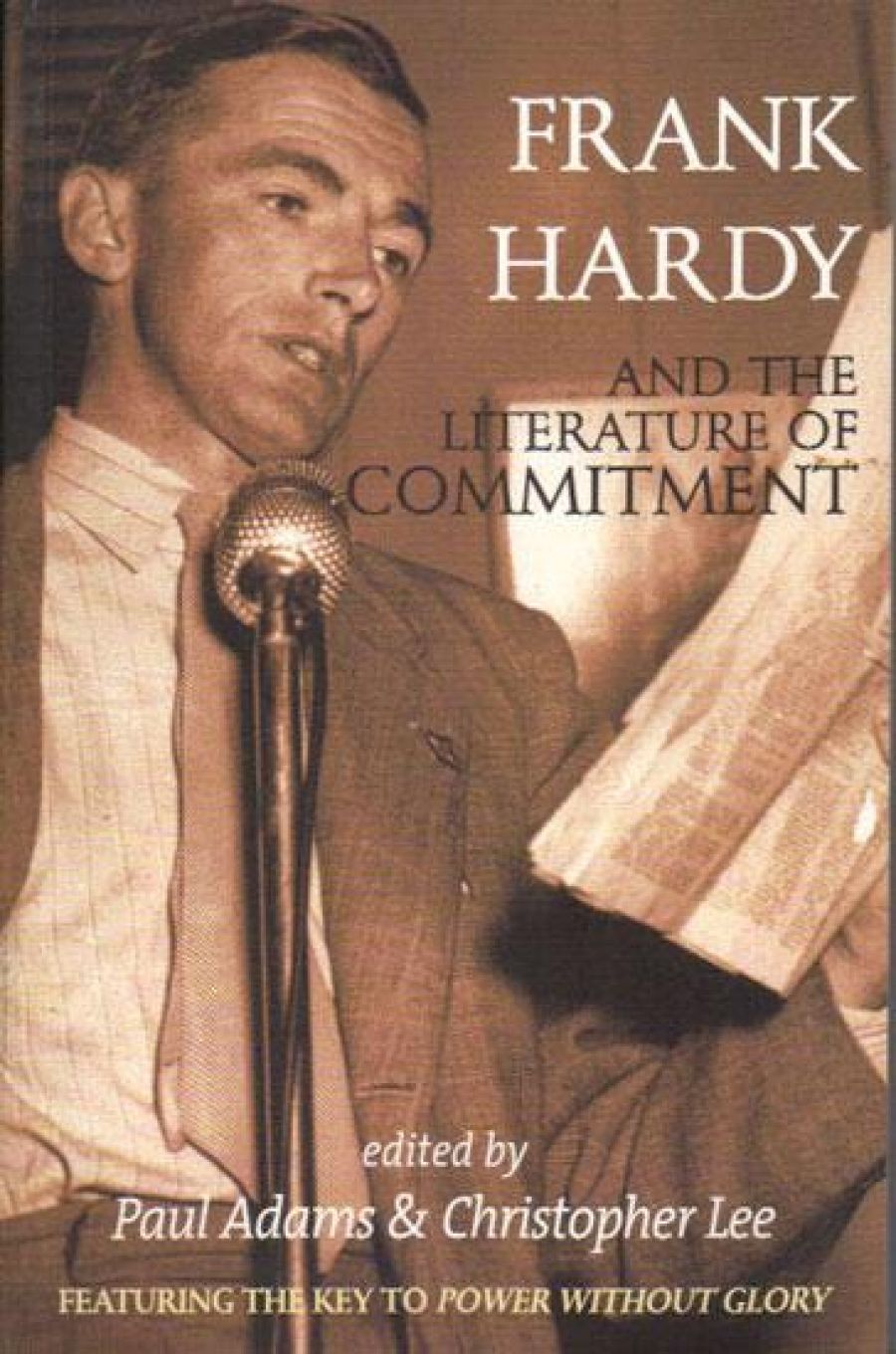

The title, cover and blurb of this collection of essays, articles and interviews promote it as a sequel to editor Paul Adams’s literary biography of Frank Hardy, The Stranger from Melbourne (2000). The invocation of the iconic writer, communist and media personality’s formidable reputation should ensure reasonable sales, but it is to the detriment of the book’s internal logic and thrust that Adams and his co-editor, Christopher Lee, underplay the contribution of other communist writers of his era. Several chapters in the book do focus on the work of Jean Devanny, Dorothy Hewett, Katharine Susannah Prichard and Ruth Park, but (in a manner similar to how their works were dismissed in their own time) the prioritisation of Hardy as the definitive communist writer ensures that they play second fiddle.

- Book 1 Title: Frank Hardy and the Literature of Commitment

- Book 1 Biblio: Vulgar Press, $39.95 pb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

That is a pity, because better sequencing and sub-division would have made this collection more accessible. It is essentially a book in two parts. Chapters Two to Five examine the tension between communist literature and the Communist Party. Had it been placed first rather than fifth, David Carter’s definition of a communist novelist might have provided a valuable inroad into this difficult subject area. By comparing Hardy’s first novel, Power Without Glory (1950), which was notorious for the scandal surrounding its allegedly libellous content, with Judah Waten’s Time of Conflict (1961), Carter’s essay underlines the difficulty of making fiction a vehicle for ideology and of locating communist literature within an Australian tradition. Had Gardiner’s and Carter’s essays been swapped, the rest of the sequencing of this section could have stood. John McLaren’s essay, ‘Bad Tempered Democrats, Biased Australians: Socialist Realism, Overland and the Australian Legend’, provides a detailed analysis of how the collective means of producing Power Without Glory ramified through the Communist Party and later served as a model for the leftist journal Overland.

The focus then widens appropriately with Carole Ferrier’s examination of Hardy’s professional relationships with Devanny and Hewett, which illuminates not only the influence that Communist Party membership had on their work but also how uneasy the otherwise radical party members were with the similarly progressive ‘sexual politics’ of the women’s novels. This consideration of personal failure within internal party politics is further explored in the reprint of Peter Williams’s defence of Hardy against an attack by Jack Beasley (sometime editor and secretary of the communist Australasian Book Society) in his memoir ‘Red Letter Days’. With the appropriate familiarisation granted by these preceding essays, Allan Gardiner’s chapter on the short-sighted attitude of the Communist Party to its literary wing could have provided a fitting close to a complex topic that doesn’t need to be made more inaccessible than it already is.

The book’s other half focuses on close textual readings of Hardy’s, Prichard’s and Park’s work. It would have benefited from sub-categorisation and some judicious rejigging. Again, the first chapter of the subject – John Frow’s reduction of Hardy’s work to an echo chamber of intertextuality – lessens rather than encourages perseverance and should perhaps have been placed last, along with Hardy’s own posthumously published ‘Frank Hardy’s Last Blast in Defence of Truth’ and Paul Adams’s exhilarating deconstruction, ‘Intertextuality, John Frow and Frank Hardy’. Perhaps the section should have begun with Cathy Greenfield and Peter Williams’s focus on the aspect of ‘strangerism’ existing in Hardy’s writing (‘Strangers in the Camp: The Politics of Frank Hardy’s Writ-ing’), followed by the two essays by Delys Bird and Cath Ellis on the politics of race (‘The Politics of Race and the Possibilties of Form in the Work of Katharine Susannah Prichard’) and ideology (‘The Triumph of Ideology: Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Goldfields Trilogy’), respectively. Nathan Hollier writes interestingly on Hardy’s invocations of traditional Australian masculinity (‘Frank Hardy and Australian Working-class Masculinity’), an aspect of his work that makes much of it unattractive to modern, gender-politicised audiences. Taking another slant, Paul Genoni studies both Hardy’s and Park’s work from the perspective of their disavowed Catholicism and the subsequent dogma of their political ‘faith’ (‘Ruth Park and Frank Hardy: Catholic Realists’).

The collection ends with Dave Nadel’s ‘Key to Power Without Glory’ (1976), which, though interesting as an historical artefact, doesn’t have much to do with the rest of the collection and would have been better featured as an appendix along with the Morphett interview. The inclusion of this key without its referent also underlines the irony of such a sizeable literary study being devoted to an author whose work is largely out of print.

In some ways, then, this collection seems premature. Though Vulgar Press has recently republished Jean Devanny’s Sugar Heaven (1936) and Dorothy Hewett’s Bobbin Up (1959), it remains to be seen whether this collection will generate sufficient interest in Hardy and Prichard to make reprints of their work financially viable. If it does, this otherwise esoteric selection will become an eclectic companion and a goldmine of prefatory material.

Comments powered by CComment