- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Feminism

- Custom Article Title: Mad about the Boy

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mad about the Boy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Taboo – or not taboo? That is the question you soon start asking yourself if you bother with the text of this book and its purported revelations on the subject of ‘male beauty’. It is a stimulating question, but you end up wondering if the publishers, at least, mean you to go to such bother when they’ve hardly gone to any themselves, in the way of editing, to ensure some cogency in their celebrity author’s arguments. There’s little here, in fact, that you could call argument, in the sense of a coherent succession of reasoned propositions: nothing so solid or stable to argue against; nothing so stolid or boring. When not beguiled by the next image of upwardly nubile flesh, sumptuously reproduced from the work of the world’s great visual artists, you’re more at risk of being left stupefied by the next authorial assertion. Oh, yes, it will be provocative, but the provocation often lies in its brazen countering of the assertions that have preceded it. Silly you for craving consistency.

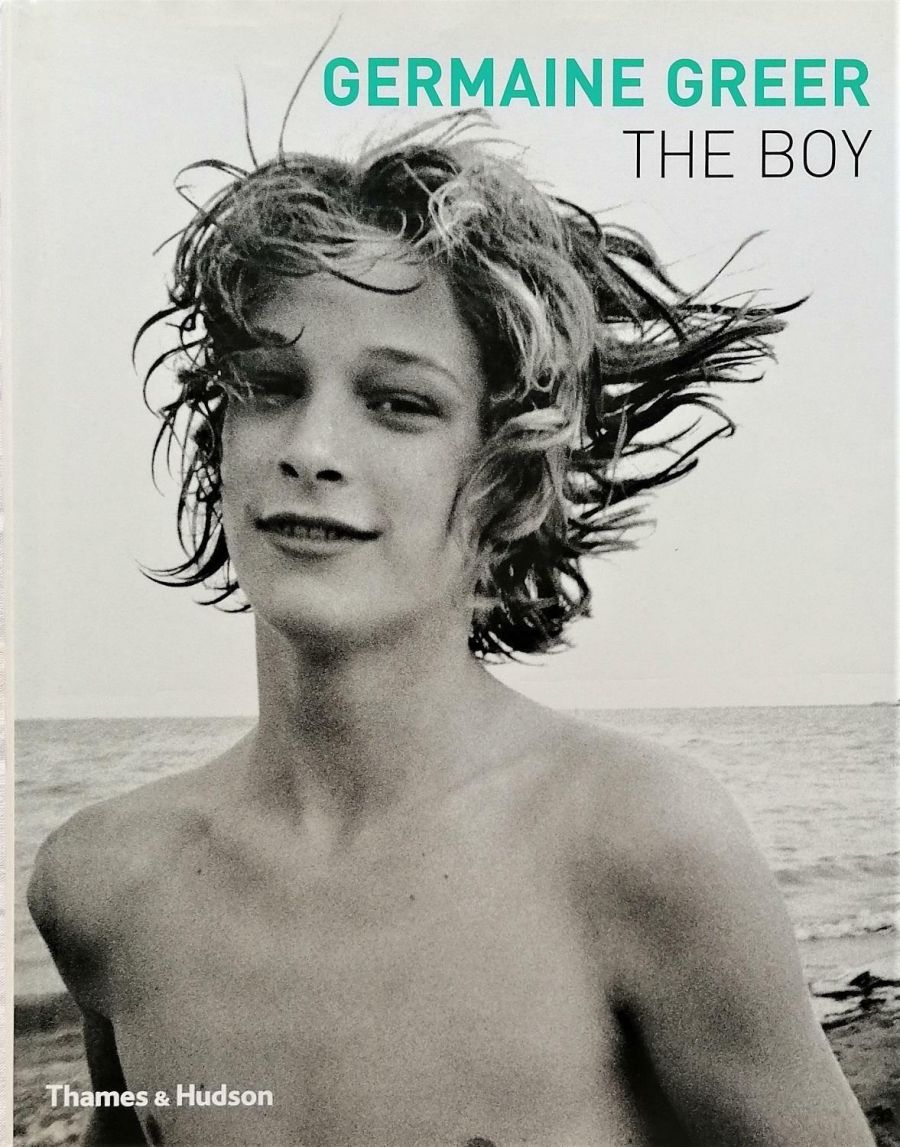

- Book 1 Title: The Boy

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $90hb, 256pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

‘I’d like to reclaim for women the right to appreciate the short-lived beauty of boys,’ asserts the author on the back cover – a neat encapsulation of two related taboos that, by her account, continue to afflict our seemingly liberated society. The physical attractiveness of the boy, defined in the opening line of her first chapter as ‘a male person who is no longer a child but not yet a man’, and the particular attraction for women of this evanescent portion of the human species: these are for Germaine Greer universal truths and universal goods – but far from universally acknowledged ones. In current mainstream or bourgeois cultures, in particular, it’s become general practice, if not to stigmatise, then to censor or ‘elide’ these basic human traits and appetites. Twentieth-century ‘guilty panic about paedophilia’ (her words) has compounded this ephebophobia (if I may coin a word of my own), to the extent of criminalising ‘awareness of the desires and charms of boys’, just as ‘the nineteenth century denied women any active interest in sex, which was only to be found in degenerate types’. That’s about as succinct a summary as I can manage of what appear to be the main assertions in the book, but I must apologise at the outset for sullying them with any appearance of clarity or settled conviction, and, in advance, for persisting in treating them as arguments that can or need to be tested by anyone but the author herself. For, at the outset of her own text, she foreshadows her transcendent talent for turning apparent self-contradiction into a virtue. Her preface insists that a boy ‘has to be old enough to be capable of sexual response but not yet old enough to shave’, and this is oddly consonant with her definition in that first sentence of the opening chapter where she speaks of the boy as ‘no longer a child but not yet a man’. Less odd, truer to form, are the sentences immediately following, where she blithely proceeds to describe ‘boyhood’ as ‘beginning as soon as a male baby is weaned’ and to recycle that quaint old category she has just implicitly challenged, the ‘boy-child’.

Some of her subsequent case studies in boyhood, actual or imagined, heedlessly extend the age range at the other end to include the category ‘young men’. Such individuals may be ‘well into their twenties’ (Frank Sinatra) and even sport discernible traces of five o’clock shadow, as in the photograph she supplies of rock performer Kurt Cobain, whose ‘suicide … at the age of twenty-seven made him a cult figure’. However old they were, it seems, such doomed talents were ineluctably doomed because, alive, they could ‘never outgrow their boyhood’: the publicity machine and the audience did not allow it.

On the other hand, there’s the double bind, as Greer represents it, of poor Rudolf Nureyev: ‘best known to adoring women of all ages as the devoted boy-partner of Margot Fonteyn, who was old enough to be his mother’, yet with his art confined to a succession of safe, conventional manly roles. ‘He did not have the option of dancing as a boy,’ she blankly states. What about his testosterone-tossed Romeo, you might pedantically enquire, or his rendition of the Balanchine/Stravinsky Apollo (definitely a boy-figure in other, numerous artistic incarnations invoked by Greer herself), or his own takes on doom-laden youth in Le Jeune Homme et la Mort (for French television) and the Dutch ballet Monument for a Dead Boy? Our guide to the boy doesn’t acknowledge any of these roles and once again niftily modifies her definition of the genus in question so that it’s now identified with sexual ‘mucking about’, gender bending and even species-bending, as heroically exemplified in her eyes by Nijinsky’s Faun. But Nureyev’s reanimation of this role, when in his thirties no less, goes unacknowledged, too.

If it is ‘part of the purpose of this book to advance women’s reclamation of their capacity for and right to visual pleasure’ in boys, from about when does its author date the retreat of any such claims? In one chapter, she goes so far as to identify a particular moment in the nineteenth century at which, so she puts it, ‘the age-old collaboration between mature women and boys in search of sexual enlightenment was at an end, officially at least’. (This was in 1870, when the painter Edward Burne-Jones, requested to expurgate his representation of a scantily clad mythological couple out of Ovid, chose instead to withdraw it.) Yet Greer plays as fast and loose with chronology as with definitions, and there are so many points on this switchback ride where she fails to acknowledge complicating evidence that you begin to sense it’s she who is doing a lot of the ‘eliding’ for the sake of a momentary frisson or an arresting phrase.

A previous chapter sports the marvellously arresting title, ‘The Castration of Cupid’, but here it’s to the eighteenth century she ascribes the attempt to ‘desexualize the subject’, while claiming that ‘by the mid-nineteenth century the winged boys had clawed their way back to the forefront of public art’ and ‘naked boys sporting wings are to be found on all kinds of public monuments’. As her evidence in this case consists of nothing more systematic than a handful of images reproduced from paintings or sculpture of the period in question, I don’t feel so irresponsible in adducing just one counter-example that I happened across while writing this review.

Even if it’s an exception to the general eighteenth-century rule (and that remains to be proven by more comprehensive research), Hugh Douglas Hamilton’s Cupid and Psyche in the Nuptial Bower, dating from around 1793, is a ravishing reminder that mutual concupiscence of boys and women was never totally eclipsed as an artistic subject. Or, to put it another way, it sows a suspicion that censorship and frank affirmation of such themes are not as easily divisible into separate periods as our guide is inclined to make out. Various scholars specialising in the nineteenth century have sought for many years to dispel its sexually benighted reputation. And, in the twentieth century, aside from the cult of Nijinsky or the cult of Cobain to which Greer herself draws attention, we have the plangent testimony of that perennial hit tune by Noël Coward, ‘Mad about the Boy’, originally scored for four voices representing a wide range of female types (‘society woman’, ‘schoolgirl’, ‘cockney’, ‘tart’).

‘By the end of the twentieth century,’ Greer has to concede, ‘female appetite for sexual stimulus had been recognized and platoons of male strippers mobilized to take commercial advantage of it.’ But, typically, to retain her ground, she shifts it once again and signals a new mission: ‘That healthy appetite should now be refined by taste’ and by the nurturing of ‘civilized pleasure’. The vision this conjures up is more wondrous than that of any other leap in her argument or career to date: Germaine Greer as feminist avatar of Kenneth Clark. But forgive me for hankering after that connoisseur of the down-and-dirty, Mae West, swaggering down the middle of a catwalk in the film version of Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge (1970) and exhorting the line-up of bedenimed studs she eyes on either side of her: ‘C’m’on boys, get out your – résumés’.

Comments powered by CComment