- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Some Kind of a Man

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

By chance the other day, watching British director Herbert Wilcox’s toe-curling ‘Scottish’ whimsy, Trouble in the Glen (1954), one of Orson Welles’s worst films (one of anybody’s worst films), I was struck anew by the fact that even when Welles could not save a film, he was always sure to be remembered in it. Here he plays a Scottish laird, long absent in South America, who returns to take up the castle he has inherited and, failing to bring a castful of theatrically canny Scots to heel, admits his errors and ends by presiding – benignly, but still presiding – in a kilt, yet. A romantic liaison and an appalling little girl taking her first post-illness steps may be intended to warm our soured hearts, but it is the massive figure avoiding the worst punishments for hubris that grabs what is left of our attention.

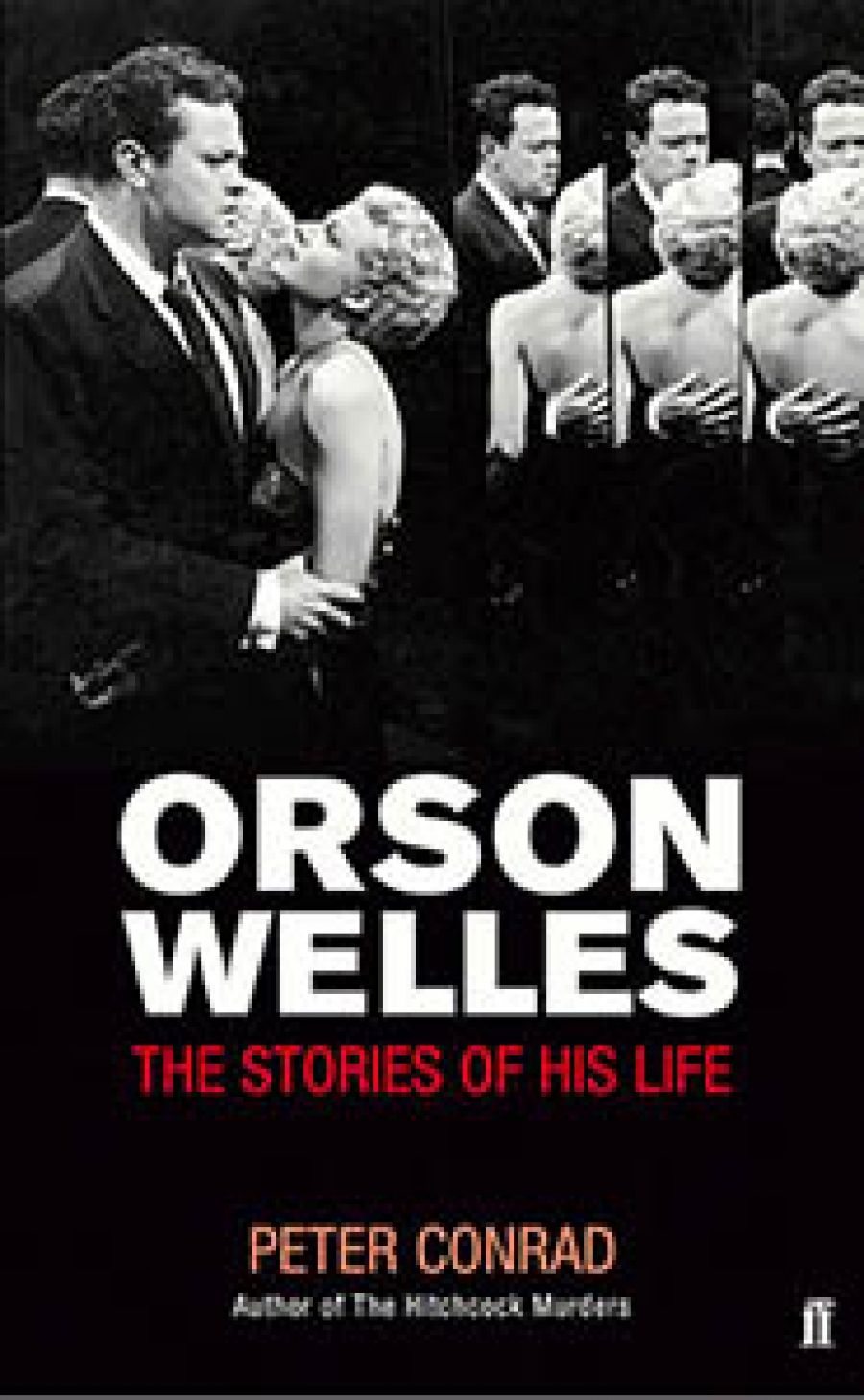

- Book 1 Title: Orson Welles

- Book 1 Subtitle: The stories of his life

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber, $49.95 hb, 397 pp

As it always did. Has anyone else known so unerringly what to do with a close-up? Is there anything more deviously engaging in film than that first shot of Harry Lime’s face suddenly visible in a dark Viennese doorway in The Third Man (1949), unless it’s the same face smiling subtly again but this time almost imploring his old friend to shoot him in the sewers at the end? Or Charles Foster Kane’s lips dominating the frame as he suspires ‘Rosebud’ at the end of Citizen Kane (1941), or Falstaff, still smiling gamely but with eyes registering the pain of rejection in Chimes at Midnight (1966)?

These are the kinds of images and memories with which Peter Conrad’s wildly ambitious non-biography is bursting. Dismissing at the outset any claims to biography, he offers the unravelling and exploration of a very complex man in whom contradictions were juxtaposed only to be worked out again and again in one of the most audacious careers of the twentieth century.

Welles’s life was chronically messy. He had three failed marriages, most famously with Rita Hayworth, whom he starred with (and shot, shattering her image the while) in The Lady from Shanghai (1949). He never considered the possibility of immortality through any of his children, to whom he must have been the most haphazard father. He recreated the facts of his early life to suit his own myth-making purposes, and he seems to have ‘conducted his private life as if it were an extension of the roles he played’. Perhaps there was more chance of coherence on film or stage; but, again, he so serially botched the financial arrangements underpinning his artistic enterprises that it is a wonder most of them got made at all. What kind of ineptitude can have allowed him to junket off to South America and leave The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) to be hacked about by RKO? On the other hand, what kind of tenacity was needed to keep his idiosyncratic version of Othello (1952) afloat as he raced off to act in other people’s films to provide the wherewithal for his own?

Conrad’s densely argued, profusely illustrated (by examples, rather than the sparse photographs) weavings and diggings find both grandeur and poignancy in the sheer magnitude of Welles’s aspirations. The achievements are unique and undeniable: fifty years on, Kane is still regularly voted ‘the greatest film ever made’ (see Sight and Sound’s ten-yearly round-up of critical choices); The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) one of the most rigorous exercises in nostalgia ever made; Touch of Evil (1958), which he directs and stars in, as the corrupt detective Quinlan, to whom Marlene Dietrich (erstwhile sawee in his magician’s act) delivers what may be Welles’s best epitaph (‘He was … some kind of a man’); and heartbreakingly Falstaff in his own magisterial reworking of strands from five Shakespearean plays in Chimes. These would be enough to ensure his place among those at the top of cinema’s creative pantheon.

There is poignancy in the way his artist’s intransigence and wheeler-dealer incompetence frustrated so many of his endeavours. Conrad, in telling the stories that make up Welles’s life, knows that there is at least as much of Welles in the ones that didn’t get made, above all perhaps in his abortive attempts to film Don Quixote. By this time, he was too fat to play the knight and was settling for Sancho Panza, but, as Conrad notes, it was a case of ‘the mind of Quixote in the body of Sancho’. There was about Welles, at this time, an aura of the ruined romantic, the ‘blinkered enemy of modernity’. And it is hard not to be moved by the idea that, unable to finance his own projects, he was forced to act in other people’s often lesser works. It was one thing, as racketeer Harry Lime, to pick up The Third Man and run with it, so that it now seems as much Welles’s film as director Carol Reed’s, but his hired-hand work didn’t always find such distinguished company. He made, for instance, a film by Michael Winner – though, while he is on the screen, even this, I’ll Never Forget What’s ’is Name (1967), rivets the viewer.

Conrad brings a formidable battery of talents to the daunting challenge he has set himself in illuminating the man through the work, and, if I concentrate on the films, that’s because these are what we have continuing access to. These are the ‘stories’ in which the life is unfolded, fragmentarily, for certain, but also inexorably. Conrad is clearly saturated in Welles’s oeuvre and consequently can dart about it with confidence, grasping at explanations or throwing up hypotheses. He chooses to trust not history but ‘myth, with its cruel cyclical justice, its rises and falls and eternal returns which reassure us that, although everything is mutable, nothing changes’. So did Welles, who valued stories most because they preceded the teller – and outlasted him.

One is struck often by the astuteness of Conrad’s insight and phrasing: of the bleaching of Hayworth for Shanghai, he claims Welles made ‘her look like a photographic negative of herself’; or about the function of Welles’s voice-over for King of Kings (1961): ‘Visually we are restricted to what happens in the present, but words can foretell the future.’ His intellectual range and grasp, hurtling across millennia, continents and media, often amazes, even if it also sometimes wearies; and the strategy, the use of films et al. as fragments of autobiography, is demanding, as Conrad dips in and out of the Wellesian decades. There are no footnotes and, while it is flattering to be expected to know all that Conrad knows, there are times when I would have valued a gloss on some more than usually arcane reference.

It is not that Welles began at the top and the rest was downhill all the way; rather, it was hard to maintain the Kane plateau. He is an artist (and near the end of his life he, movingly, wondered if art had been enough) whose art and whose life may well be summed up as a labyrinth without a centre, as Borges suggested. The circularity of the stories of his life is encapsulated in the bookending figures of Kane, whose youthfully aggressive zest settled into prosthetic old age, and Clay, in The Immortal Story (1968), whom age has forced to turn to youth for vicarious and voyeuristic gratification. They are not the beginning or end of Welles’s career but between them they encompass most of it. Like Conrad’s book, they evoke the man and the life rather than merely describe them.

Comments powered by CComment