- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

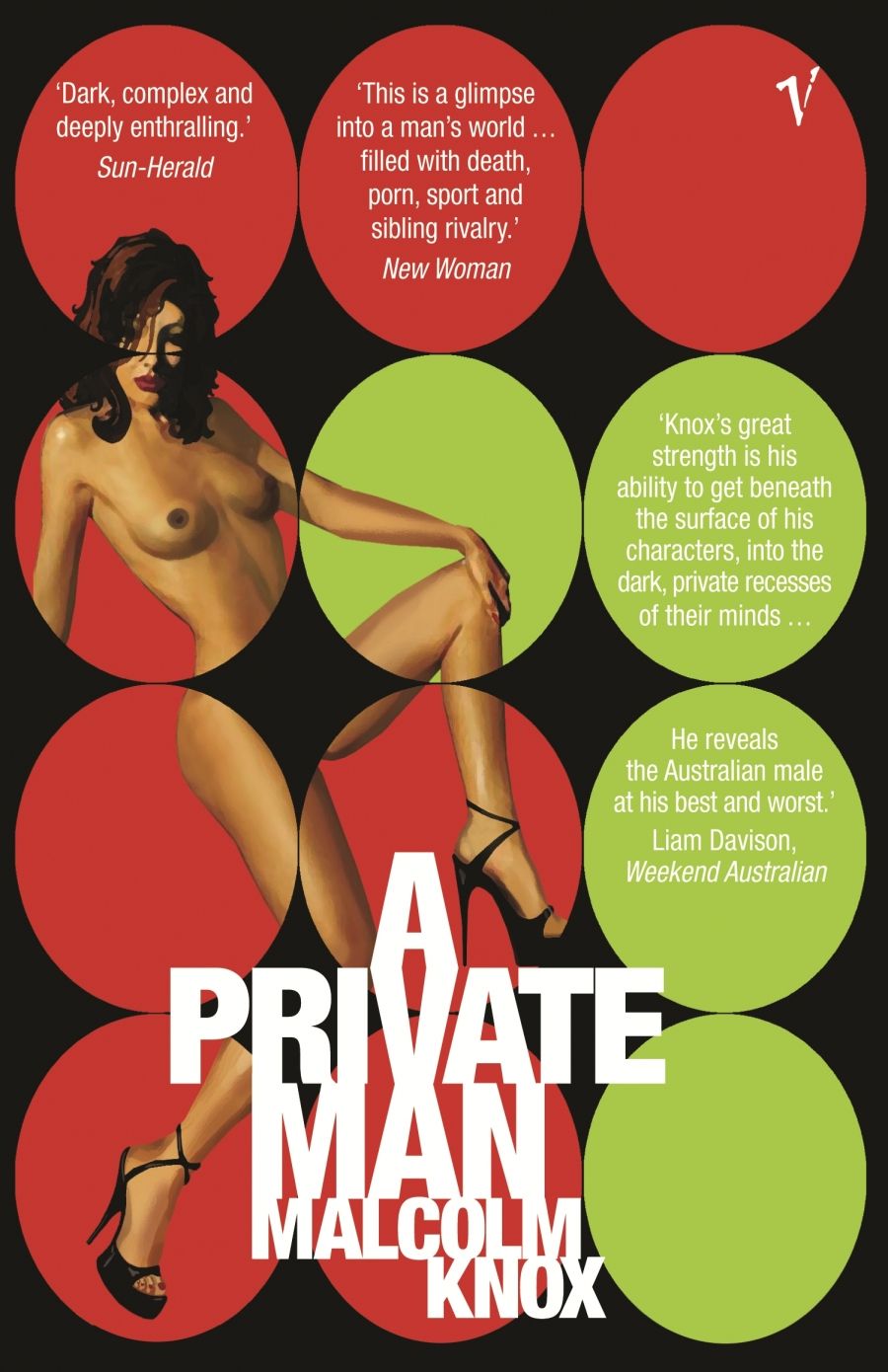

Gabriel García Márquez once said that all of us lead three different lives simultaneously: public, private, and secret. In his second novel, A Private Man, Malcolm Knox explores two very secret recesses of the modern Australian male’s experience: porn and sport. That both these spheres also have a very public face merely allows for these secret experiences to be played out in front of a paying audience as either tragedy or farce, or sometimes both.

- Book 1 Title: A Private Man

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $29.95 pb, 385 pp

The extraordinary domination of Australian culture by sport is obvious, except perhaps to those of us who have only ever experienced an Australian upbringing. I remember a recently arrived Englishman innocently asking who Don Bradman was the day the latter died. Everyone around him thought that the Pommy was being ironic, a defensive irony in retaliation for the many times ‘The Don’ had humiliated his national team on the field of cricket. But he wasn’t joking. He genuinely didn’t have a clue. And even when we explained, he remained puzzled at what the fuss was about – he was, after all, just a sportsman, wasn’t he?

Apparently, every red-blooded Aussie male, from Prime Minister John Howard down, has harboured the fantasy of opening the batting for Australia, or kicking the winning goal in an Australian Rules grand final, or winning the 100-metre swimming final at the Olympics by a fingernail. The countless hours spent in lonely bedrooms by Australian teenagers every year fantasising about doing one or all of these things is possibly only outdone by the fantasising played out in front of computer screens in offices, classrooms, and dens across Australia as old and young download a fresh shipment of cyber porn.

The central character in A Private Man is Dr John Brand, a respectable sixty-seven-year-old doctor living in the leafy North Shore of Sydney. He has a wife, Margaret, and three adult sons: Davis, Chris, and Hammett. So far, this sounds like any 1960s American sitcom’s fantasy of family life. But Dr Brand is also hopelessly addicted to pornography. He sneaks off to grubby suburban porn shops to buy ‘stick mags’, and, in one outrageous scene, steals away to his study at home for an unzipped frolic with his laptop, while his entire family is downstairs preparing for dinner. The utter madness of this behaviour reminded me of the risks John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton must have taken when they had sex in their offices, and how the erotic charge must have had more to do with the risks than the actual sex.

For John Brand, pornography has become an obsession. For his sons, it is much more banal. Sometimes a marital aid, often a joke, and, for Hammett, a way of earning a living, porn is always there, always available, always consumable – it’s just a matter of what kind of perversion one wants, what articulation of which body parts, and what key words one types into Google. But for the doctor, the instant availability of such outrageous images on the Internet came as a revelation when he was sixty-two, leading to addiction and, with it, profound shame.

There are very few directions a plot like this can go, and the inevitable happens: John Brand is ‘sprung’ and, after a series of tragicomic misadventures, he dies on New Year’s Eve, in slightly sordid circumstances. But Knox is smart enough to realise that a linear narrative about the decline and fall of a bourgeois patriarch could only get him so far. So the novel opens up to encompass the whole family, their secrets and psychodramas, their repressed memories and overblown mythologies.

As well, Knox adds an artfully underplayed thriller element, as John’s eldest son, Davis, tries to uncover the unsavoury truth about his father’s death. Davis has followed in his father’s footsteps and become a doctor, but feels he has never received the respect he’s due from the rest of the family. Meanwhile, the sporting element takes the front foot with middle son, Chris, who, after a string of low scores, is fighting for his cricketing life in the Australian team playing against South Africa in the New Year’s Test at Sydney. The youngest son, Hammett, is the outcast, the runt of the litter who disappeared years ago, making a career out of producing and distributing porn, until a chance encounter brings him back to the family again. Finally, there’s Margaret, the matriarch, enthroned at home in her North Shore lounge room, torn between grief for her husband and watching her favourite son play the innings of his life on television.

There are echoes of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections in the structure and familial focus of the book – and I mean that in the most complimentary way. Chapters weave back and forth in time and take the point of view of first one then another of the main characters. The result is that, with each new chapter, we see different sides of each player. Our sympathies grow and ebb, and each character’s personality seems much more rounded and believable as a consequence.

The final and deepest secret for us all is death; and even here the secretive Dr Brand is true to type. He is dying of cancer but cannot bring himself to tell his wife or sons. There is an attempt at revelation late in the piece, which is significant and leads to the possibility of a reconciliation among the three brothers and the all-controlling Margaret.

In the end, the three sons ring in the changes: Davis exchanges a postmodern marriage of convenience for someone who could be his true love; Chris gives up cricket to be with his wife and kids; and Hammett regains his family, though it’s not clear that he’ll give up the porn business. After all, someone’s got to keep the economy ticking over.

Comments powered by CComment