- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Big Bertha

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Last summer, Peter Booth became the first living artist to have a full-scale retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria’s Ian Potter Centre at Federation Square. With eighty-one paintings and 150 drawings, it ranked as one of the largest surveys ever accorded a contemporary painter. It was a bold move on the gallery’s part and made a claim for Booth’s pre-eminence within his generation. Surprisingly, there were no interstate takers for the show.

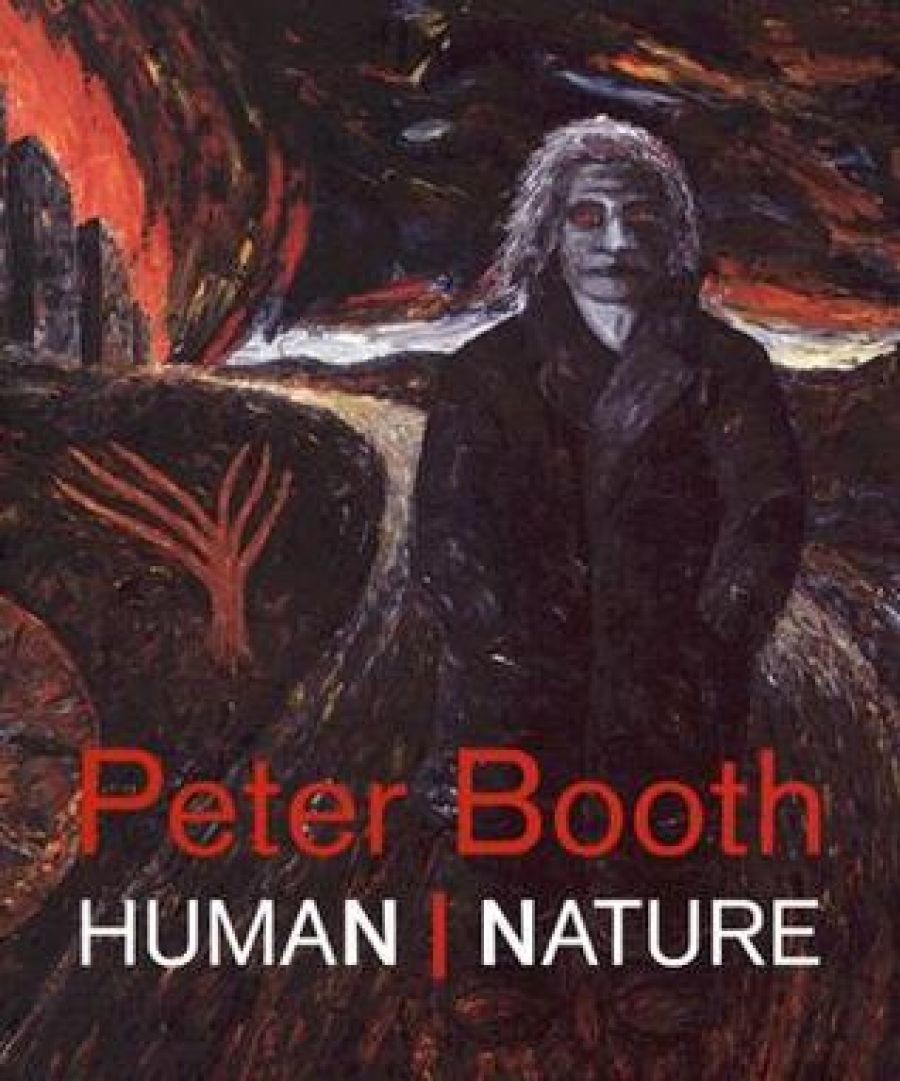

- Book 1 Title: Peter Booth

- Book 1 Subtitle: Human/Nature

- Book 1 Biblio: NGV, $39.95 pb, 152 pp

Even allowing for the vagaries and bad economics of Australian art publishing, it is astonishing that no monograph has appeared on Booth, now in his mid-sixties and with almost forty years of serious painting behind him. The exhibition catalogue, here as elsewhere, becomes the comprehensive account of the artist’s work. The principal authors, Jason Smith, Curator of Contemporary Art at the NGV, and Robert Lindsay, a previous occupant of the post, know the artist and his work well. When Federation Square opened, Smith devised the striking gallery, that paired Booth and Bill Henson – an Antipodean ‘heart of darkness’.

Booth has had a career like none other amongst his contemporaries. A contributor to The Field in 1968, he moved from minimalist abstract works to the black ‘doorway’ paintings, which were like the crack of doom, impenetrable and implacable. In the mid-1970s he turned to a series of dense, painterly abstractions in high-keyed colours, still some of his finest paintings and amongst the best pictures produced in Australia at the time. Booth’s abstractions felt freighted when such notions were discounted.

Then came the big change of 1977, when Booth showed his large-scale, virulent figure paintings. They sure had the shock of the new. Robert Lindsay rightly points out that they came from within Booth and his studio practice, and not as a result of external influences, for example. The big shows that heralded the revival of expressive, figurative painting – Weltkunst (Cologne), A New Spirit in Painting (London), Zeitgeist (Berlin) – all came after Booth’s breakthrough. The fast and furioso figurative paintings of 1977-87 gave way to the spare, snow-ridden landscapes, ranging from the plains of Siberia to English woods remembered.

At each stage of his retrospective, Booth comes across as a burdened artist. That burden is what Smith and Lindsay seek to unpack. Their modus operandi is to hurl big words, high-end concepts, and luxuriant quotations at the paintings, hoping that something will stick. Rhetorically, they strive to go toe-to-toe with the paintings.

Smith launches his essay thus: ‘The essential human conditions identified by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita correspond directly with those embedded and elaborated in the life and art of Peter Booth.’ Not to be outdone, Lindsay tells us that in a series of black-and-white gouaches of 1975-76:

Booth began to map an odyssey that would become in later paintings an epic chronicle of the collapse of civilization, the rise and demise of man and the emergence of post-Holocaust mutants, heading towards a long, cold winter of ecological hibernation.

After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Such an overheated response is not altogether useful. In his essay ‘Hard Rain: The iconography of Peter Booth’, Robert Lindsay strives so consistently to elevate the artist into the sublime that we lose touch with the pictures. At one point, Lindsay mentions in the space of four lines Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, The Iliad, The Odyssey, and The Aeneid. All this clangour is a pity because, squirrelled away amongst the rhetorical barrages, both Smith and Lindsay make some interesting points. Both draw useful attention to Peter Booth’s Sheffield background, although the claims of remembering air raids during World War II strain credibility; Booth was barely four when the last German air raid occurred. Smith makes good use of George Orwell’s description of Sheffield in The Road to Wigan Pier, to give a vivid idea of the urban environment in which Booth grew up before coming to Australia in 1957.

Both authors are right to emphasise the role that memory – the great elixir of the imagination – plays in Booth’s art.

The authors dwell on the importance of Booth’s time under John Brack’s tutelage at the Gallery School and his subsequent period as a technician in the Print Room at the NGV, where he came across, firsthand, Goya and Blake, especially the latter’s Book of Job: a testimony to suffering. Likewise, Smith and Lindsay point to the important influence of Les Hawkins, a fellow technician at the NGV and a curious savant, who encouraged younger artists and led them to authors and books they might not have otherwise encountered.

Rather bravely on the part of both artist and curator, we are told of Booth’s epilepsy and its possible cause in a violent and irrational incident in the artist’s own home. Rightly, Booth has always been guarded about discussing his inner, private life, not wanting to distract from the work itself. Smith draws a useful distinction between the autobiographical and the self-portrait in Booth’s work – a distinction that could have stood further elaboration.

The ‘work itself’ remains the issue. Both authors might have been more mindful of the artist’s own observation that ‘the painting takes over. It must follow its own course.’ The Big Bertha approach, with its determination to lift Booth into the empyrean, obscures his quality and distinctiveness. Ted Gott, a fellow curator, once made a shrewd observation that Booth’s art ‘involved pitting oneself against visual obstacles’. The struggle and the release from struggle within Booth’s paintings are more usefully observed than taxing the pictures with the future of mankind, the survival of the planet and the spiritual unification of all living things.

Useful as it is to have Booth laid end to end, the catalogue is irritating to use. All but two of the plates have neither titles nor dates, simply catalogue numbers, so that one is constantly flicking back and forth to the checklist to see when and where a painting or drawing was made. The two exceptions refer to Booth’s paintings in the Metropolitan and the Guggenheim in New York, neither of which was included in the show – a pity.

Lastly, the author of a retrospective catalogue who makes two mistakes in one name should pause for self-reflection. I take it that by ‘Casper David Frederick’ Mr Lindsay is referring to the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich. Somebody should have caught that one in the slips.

Comments powered by CComment