- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bessie in Paris

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

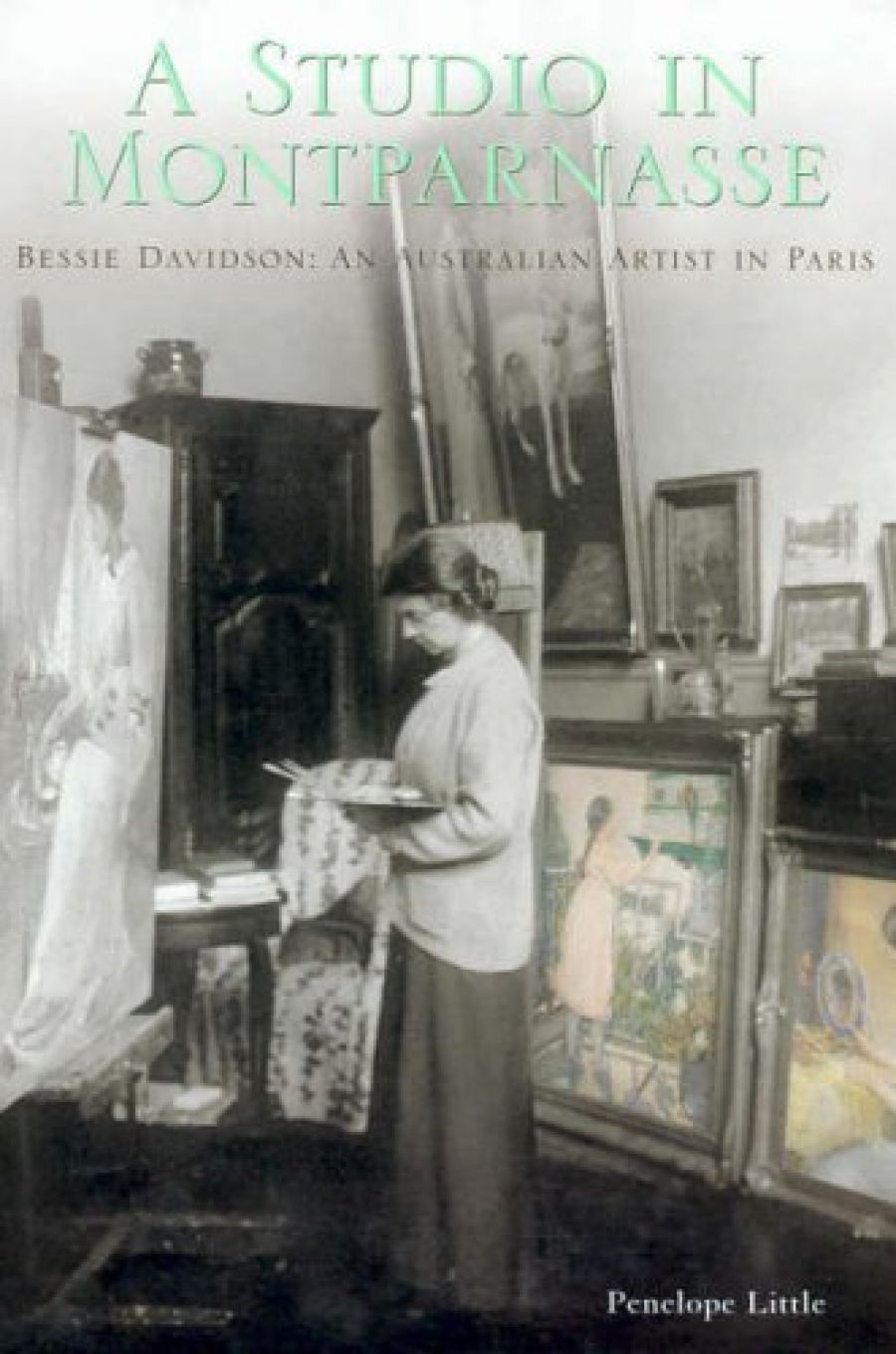

Australian expatriate artist Bessie Davidson was a woman who ripened with age. After decades of living in Paris and dressing somewhat dowdily ‘à l’anglaise’, she gained confidence with the liberation of France towards the end of World War II. In her sixties, she adopted a long black cape, a wide-brimmed fedora and a slender black cigarette-holder. Penelope Little’s A Studio in Montparnasse: Bessie Davidson: An Australian Artist in Paris similarly improves as it goes along, becoming increasingly engaging as the artist is brought to life and found to be in the midst not only of two world wars but also of bohemian interwar Paris.

- Book 1 Title: A Studio in Montparnasse

- Book 1 Subtitle: Bessie Davidson, an Australian artist in Paris

- Book 1 Biblio: Craftsman House, $60 hb, 223 pp

After plodding across several centuries of the artist’s Scottish ancestry, Little hits her stride when describing Davidson’s conservative Adelaide upbringing and her early tutelage under Rose McPherson (better known as Margaret Preston), with whom in 1910 Davidson first headed to Europe. Part of Little’s struggle to breathe life into her protagonist in those early years is due to the lack of surviving primary sources, particularly letters or published material. The challenge of dealing with poorly documented artists has been addressed recently by authors such as Drusilla Modjeska, who have provocatively (and with mixed success) woven fiction with non-fiction. As an art historian/biographer, Little has no such recourse. But she is at her best when she has dramatic events to work with, which she does from 1914, when Davidson registered as a volunteer nurse with the Red Cross and bravely ministered to the armies of wounded and typhoid sufferers.

Davidson’s actual voice makes a powerful entry into the book with the occupation of Paris during World War II, when she was forced to live in exile and under great hardship in various regional towns across France. At this point, the author is blessed with a series of striking letters from the artist to her Dutch friend Conrad Kickert, in which she describes her well-founded fear of finding herself in a German concentration camp, the near-impossibility of keeping warm without fuel through the bitter winters, her anxiety about friends with whom contact was impossible, and her dogged determination to keep painting in the face of everything. The letters make gripping reading; it was an effective device to insert them directly into the narrative. While the book begins slowly, by its conclusion the reader is completely won over by the bravery, warmth and determination of this remarkable woman.

Davidson is mentioned frequently in recent publications on the subject of Australian women artists, but mostly as a travelling companion to her better-known friend Margaret Preston. Never before has Davidson’s life and work been fleshed out in such detail. A Studio in Montparnasse is the first scholarly and comprehensive examination of both the art and life of this most intriguing woman.

But what of the paintings themselves? One of the book’s strengths is its ability to combine art history with biography. Little’s discussion of the works is lively and relevant, and avoids interrupting the biographical narrative. Davidson was a good, if not great, artist who produced a large body of spirited post-impressionist landscapes, interiors and still-life paintings. She is best remembered today for her intimate studies of women and children set in the bourgeois interiors of Parisian apartments, many of which are well reproduced in colour at the end of the book. Davidson exhibited widely in Paris with a range of independent bodies such as the Salon National des Beaux-Arts and the Salons d’Automne and des Indépendants. Despite her commitment to, and involvement in, the Parisian art world, however, one suspects that it was her dedication as a nurse during World War I that did most to earn her the prestigious Legion of Honour, the only Australian woman ever to achieve such a distinction.

The book raises a number of intriguing questions: what was the real nature of Davidson’s friendship with the enigmatic Marguerite Le Roy (‘Dauphine’), her patron and beloved companion, in whose tomb she was eventually buried (Little is confident the friendship was platonic, but other art historians remain unconvinced); was she directly involved with the French Resistance (the book concludes that she probably was, and the evidence, though slight, tends to support this); is the painting Le Livre Vert a portrait of Preston (very likely)? The book also provides invaluable information for future historians of Australian expatriate artists living in Paris during this period.

A Studio in Montparnasse has involved painstaking – and no doubt often exciting – research in both Australia and France. Despite the existence of several typographical errors and the smallness of some of the reproductions, it is a well-produced addition to the art lover’s library. Davidson was a passionate and determined woman whose love of France and its people, as well as her gender, have relegated her, until recently, to a mere footnote in Australian art history. This book does much to rectify the situation.

Comments powered by CComment