- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Travel

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a tale of a farm boy who grew up in ‘the world of the rural poor, [which] remained what it had been for generations; a day’s walk in radius, a tight, well-trodden loop between home, field, church, and, finally, a crowded family grave plot’. It is the story of James Cook’s dramatic escape from that loop, told by another equally restless soul, American journalist Tony Horwitz, who spent eighteenth months travelling the Pacific in the wake of Cook’s three great voyages of discovery.

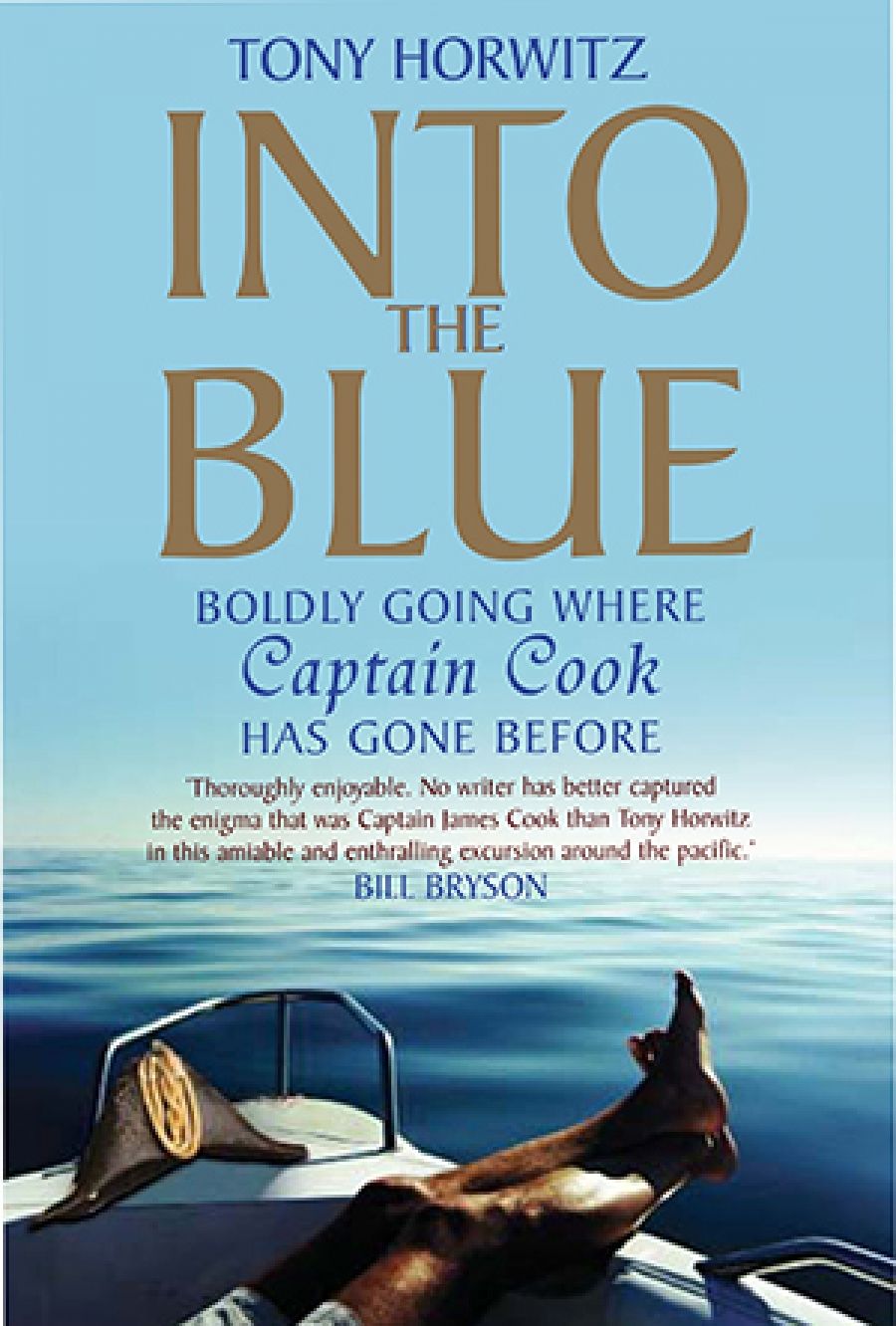

- Book 1 Title: Into the Blue

- Book 1 Subtitle: Boldly going where Captain Cook has gone before

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95pb, 480pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/into-the-blue-boldly-going-where-captain-cook-has-gone-before-tony-horwitz/book/9781741141634.html

Into the Blue is a rich mix of history and travelogue, sometimes too rich for easy digestion. It is long, for one thing, and the twists in mood and tone can be a little wearying. Although Horwitz could not track every part of Cook’s voyages, he visits many key sites, including Tahiti, eastern Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii. The book opens with verve and humour as Horwitz spends a week on the replica Endeavour. With a journalist’s ear for a telling phrase, and a vivid historical imagination, Horwitz goes on to match accounts of Cook’s travels with his own.

The book contains some marvellous passages. At his best, Horwitz fits his own description of Cook: a worldly man with no pretensions to scholarship, yet a well-balanced instinct for people’s profound cultural differences on the one hand, and their common humanity on the other. The travels and historical accounts offer many opportunities for Horwitz to exercise his perceptive and sympathetic style. I particularly enjoyed the chapter on Cook’s home turf of north Yorkshire. Led a frustrating dance by the multitude of Cook’s supposed early houses (Melbourne’s spurious Cook’s cottage being one of a whole series), Horwitz reflects on the ardent qualities of memorialising this ‘plain, zealous man’. He has a series of telling encounters, including one with a local teenager who knows little about Cook but admires him because: ‘He got out of this place didn’t he? I plan to do the same as soon as I can.’ In the bleak rain, Horwitz feels a deep sympathy for both escapees. Yet he also finds admirers of Cook who are firm stay-at-homes, such as Reg, owner of a private museum devoted to Cook, whose life is as deeply rooted in his local town as Cook’s was lived with an eye always to new horizons:

While I was drawn to Cook’s restless adventuring and plunge into the unknown, Reg worshipped the man’s modesty, sense of duty, loyalty to home and country. Maybe it was good that we knew so little of Cook’s inner life. As it was, each of us could fill him up with our own longings and imagination.

Horwitz has done his homework. An admirer of Cook’s magisterial biographer J.C. Beaglehole, he is also familiar with more recent historical and anthropological excursions into Pacific history. He includes a good annotated bibliography and uses the journals of Banks and Cook in fresh ways. He is familiar with the work of Greg Dening, and with the debate between Marshall Sahlins and Gananath Obeyesekere on whether Cook was really seen in Hawaii as a god, or whether this assumption is part of an anthropological romanticisation of Pacific peoples and cultures. Horwitz, like Cook, is an astute observer, a sharp learner and a natural humanist.

All good material for a book; but is Horwitz a good travelling companion? Oddly enough, the weakest part of the book is the account of his own travels. Undoubtedly, it is impossible to reproduce the glamour and intensity of Cook’s first contact experiences, but must they be relived as farce? Horwitz’s own travels are firmly in the genre of Bill Bryson travel writing: arch, glum and befuddled all at once. The sheer dreariness of much of the travelling is remarkable. Horwitz and his companion, Roger, stumble their way through the Pacific, often in a blur of booze and vague disappointment, relieved by occasional moments of ‘authenticity’. They find Papeete a ‘shitbox’, and their farcical re-enactment of Cook’s landing, on a family beach near Papeete, is neither fun nor perceptive, merely boorish. As they wade ashore in ridiculous costumes, Roger comments on the resonance with Cook’s experience: ‘just what Cook saw … topless crumpet.’ Call me old-fashioned, but I found Roger a complete bore. In fact, it is sobering to consider that such Australians continue to exist. Did he really exclaim in a bug-infested guesthouse ‘it is like Gallipoli up here’? And did Horwitz, who has lived in Australia and is married to an Australian, have no option but to reproduce all the tedious Australian types in his book? Roger is an English immigrant who ‘came from pale, pinched working-class stock, but during twenty years in Sydney he’d leisured himself into a handsome, bronzed Aussie … tall and broad-shouldered, with sun-streaked blond curls, and blue eyes set in a perpetually tanned face’. The thump as Horwitz shifts from interesting, good-humoured writing to the bathos of travel resonates tiresomely throughout the whole book.

When Horwitz manages to shake off Roger, as he does in New Zealand, his present-day encounters take on the power of his own humanity and deep interest in Cook’s attempts to cross boundaries of language and culture. No less good humoured, but much more open to the difficult and intricate relations of a postcolonial nation, Horwitz is particularly compelling on Maori politics, and the complexity of Hawaiian identities. In all, Into the Blue is certainly worthy of a read by the sea over summer. Let’s hope that on his next trip Horwitz leaves Roger behind.

Comments powered by CComment