- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

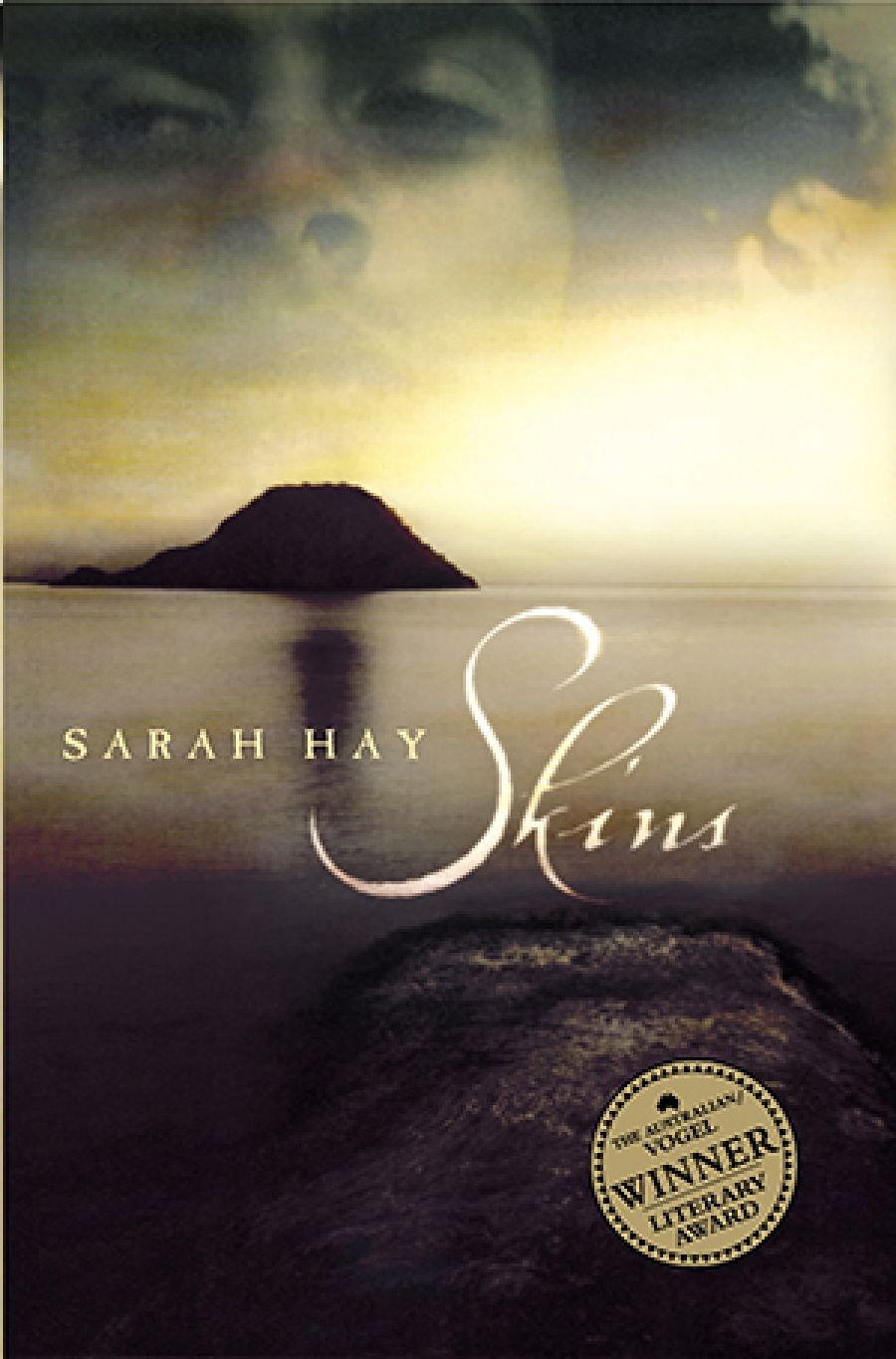

Set beyond the pale of white settlement, Sarah Hay’s Skins is a compelling and often violent story of an Englishwoman shipwrecked off the southern coast of Western Australia in 1835. Winner of the 2002 Australian/Vogel Literary Award, it is a powerful evocation of a time and place rarely featured in Australian literary fiction.

- Book 1 Title: Skins

- Book 1 Biblio: Skins Allen & Unwin, $21pb, 226pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/skins-sarah-hay/book/9781865088075.html

Hay, a former journalist, grounds her novel in research on the history and culture of early colonial Australia. Her central character, Dorothea Newell, was a real-life figure mentioned briefly in such sources as the Dictionary of Western Australians 1829–1850: Early Settlers and the Albany Court House records. Many of Hay’s other characters – including the crew of the Mountaineer (wrecked near Esperance) and the small group of men who trade seal skins – are also developed from fleeting historical references.

When the Mountaineer runs aground, Dorothea, her brother Jem, sister Mary and her husband Matthew find themselves abandoned on the remote and inhospitable Middle Island with no ready means of escape, and only a group of sealers for company. Food is scarce, although a few provisions are recovered from the ship, and the living conditions are extremely harsh. Three Aboriginal women live with the sealers and are treated as slaves, often subjected to vicious physical abuse. The newcomers are also under constant threat of violence, and struggle daily with cold, hunger and ill-health. Their future appears fragile and uncertain, until Dorothea forms a relationship with the group’s leader, Black Jack Anderson, an African-American adventurer with some education.

The great strength of Hay’s writing is its visceral quality: the detail with which she describes Dorothea kneading dough on roughly cured kangaroo skin; the misery of the cold kept at bay only by fire and piles of insect-ridden skins; and the blood-spattered brutality of hunting expeditions for baby seal skins. If the drama and palpability of these scenes can at times seem overwhelming, their power is to immerse the reader in the rawness of Dorothea’s experience. The action is intensified by the sense of isolation. The story is told primarily through Dorothea’s eyes, although sometimes interwoven with accounts from the perspective of the men in Anderson’s camp, themselves struggling for survival in harsh terrain.

The savagery of colonialism is a key theme. Recent studies by social historians, among them Anna Haebich and Henry Reynolds, alongside the work of many Indigenous artists and writers have markedly raised public awareness of the effects of colonial and postcolonial conditions on Indigenous people in this country. Yet the nineteenth century colonial imaginary remains a shadowy and contested space, open for reinvestigation and reconnection between the present and the past.

In this light, one of the most interesting aspects of Skins is Hay’s exploration of the extent to which Indigenous and settler history in Australia, post-1788, are destructively enmeshed. For most of Hay’s characters, self-determination of any kind seems almost impossible. The black women are instrumental to the survival of the whites, yet are treated as subhuman, releasing their own fury and grief in the clubbing of the seals. The white women, likewise, are under constant threat of violence, and frequent outbreaks of fighting and abuse occur among the men. ‘They are all savages,’ Dorothea comments at the outset of the story, referring to all the men on the island, sealers and crew. Yet part of her own journey in the novel involves a return to ‘savagery’. This occurs first through the fragmentation of her own ‘civilised’ appearance, beginning with the abandonment of her bonnet, and is followed by the sexual liaison she forms with Black Jack Anderson, which begins almost as a violation and develops into closeness. Finally, Dorothea embraces the ‘savage’ life, learning lessons about food and healing from the black women.

For me, the metaphor of Hay’s title, ‘Skins’, refers to the raw spoils of colonisation appropriated by the sealers, to the meeting of black and white skins both in intimacy and abuse, and to the narrow membrane of English culture shrouding the wildness of the West Australian landscape, often ruptured by violence. To some extent, Skins has its literary antecedents in the dark romanticism of previous Australian writers such as Barbara Baynton, Tasma or Marcus Clarke. Yet Hay goes further in certain keyways, for example in how she negotiates the first sexual encounter between Dorothea and Anderson, where the gesture of force is barely distinguishable from that of acceptance.

In depicting the daily struggle for survival, the everyday privations and the gruesome nature of the sealers’ trade, Hay has drawn impressively on her research and knowledge of the historical geography of the southwest coast. Skins is not a gentle story, but it succeeds in creating the small, desperate world of the group stranded on Middle Island, and in reconstructing the stories of people, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, whom history briefly recorded then forgot.

Comments powered by CComment