- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Halfway through Matthew Flinders’ Cat, the protagonist admits that, when writing, he finds it ‘almost impossible to leave out what others might think of as superfluous detail. It was, he knew, self-indulgence.’ Is this a moment of self-directed irony on Bryce Courtenay’s part, or a case of the pot calling the kettle black? This novel brims with ‘superfluous detail’, and there is little attempt to curb the flow of information.

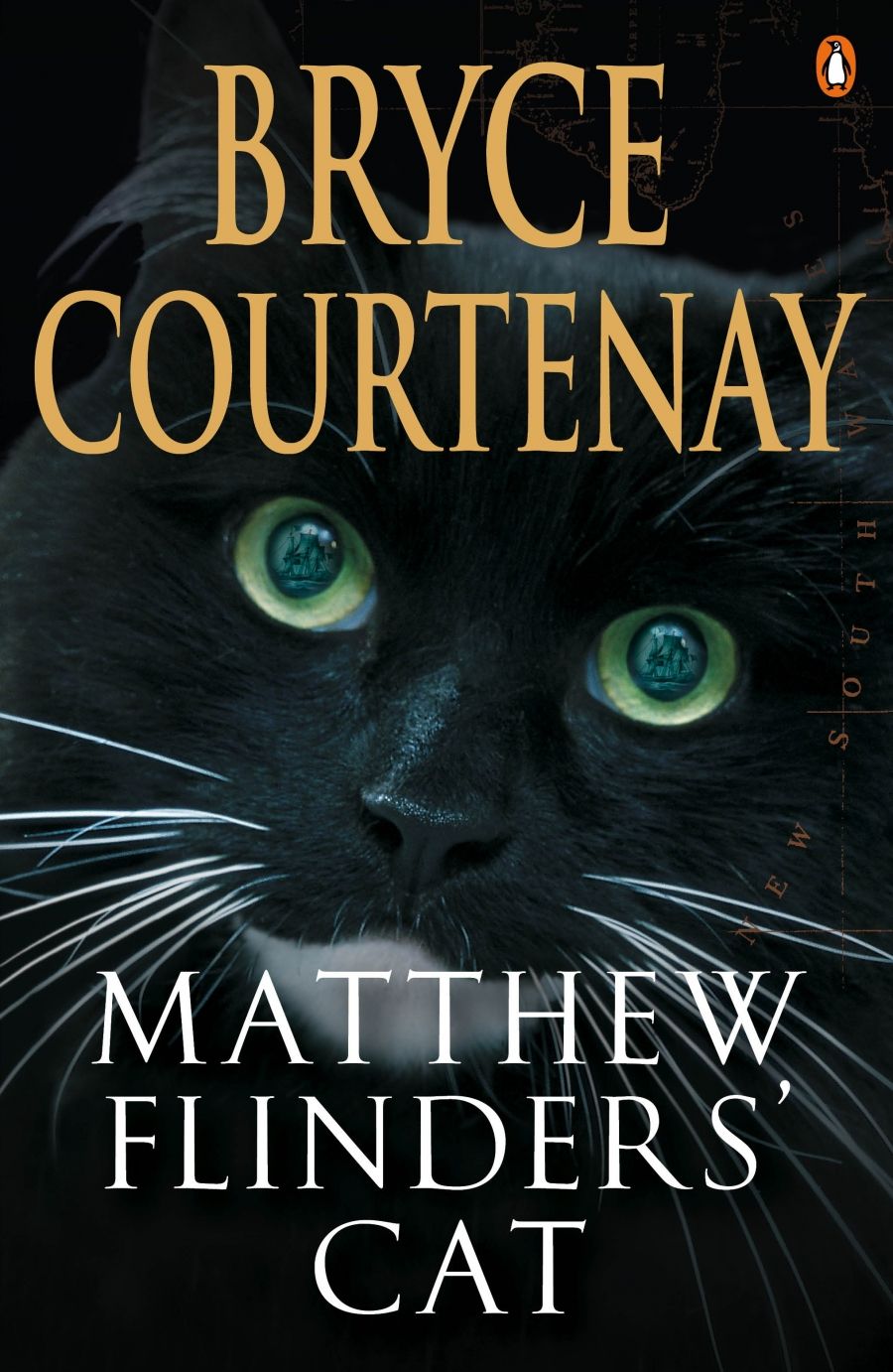

- Book 1 Title: Matthew Flinders’ Cat

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, 611pp, hb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/RzDN2

In his acknowledgments, Courtenay thanks a researcher who has indeed, on the evidence, done much work. The novel is set among inner Sydney’s homeless, and its detail abundantly proves that research has been undertaken. If you like your fiction full of information about hospital casualty departments, Salvation Army detox, and rehabilitation programs, the layout of the Botanical Gardens, or the typical behaviour of alcoholics, drug addicts and the urban homeless, this is the book for you. But you must also be prepared for stereotypes, shallow characterisations, and mountains of sentiment. Gritty realism is not part of the package.

Billy O’Shannessy is not, we must understand, just any homeless drunk. He is a former barrister, a ‘highflyer’ whose drinking ruined his brilliant career and alienated his family. After his son’s suicide, he handed over his fabulous wealth to his uncaring wife and daughter and became ‘homeless by choice’, sleeping on a bench outside the State Library, near the statue of Matthew Flinders and his famous cat, Trim. The question as to whether his was a genuinely noble act of renunciation is never really examined, although I found it hard to accept that a man with ample means is justified in deliberately abandoning it all and becoming another burden on the city’s overstretched welfare services and charities.

This quibble is probably irrelevant. Ethical issues are glanced at from time to time, but, in essence, this is a fairy tale with a moral: if you stand up and face your demons, whether they be addiction or vicious paedophile rings, they will vanish into thin air. Moreover, apart from the hardened villains who are beyond redemption, if you scratch the surface of anyone – derelict, addict or High Court judge – you will always find a heart of gold. Floods of tears are a common occurrence as characters, one by one, confess their sins or confront their misery.

Billy, at fifty-six, is an alcoholic with all the typical features that Courtenay has discovered from his research. He is paranoid, he wakes up with a dry mouth, he eats little but craves sugar, he avoids responsibility, he had a distant and bad-tempered father, and so on. Even his distinctive quality – being an educated man from a rich family – is used to make the point that ‘the big nobs of society are just as vulnerable as the rest of us if the circumstances are right’, as his Salvation Army counsellor puts it. When Billy decides to go on the wagon, however, he seems to have little trouble staying off alcohol. We are constantly reminded that an addict never loses his addiction, and told of Billy’s craving as he goes about his new life, but there is no sense that he is in serious danger of succumbing.

The novel’s rather thin plot concerns a ten-year-old boy, Ryan, son of a heroin-addicted prostitute. Ryan befriends Billy. When Ryan’s mother dies, Billy manages to save him from the clutches of a paedophile ring, using his legal knowledge and contacts to help catch the villains (who are, of course, the vilest possible villains). The demons are faced and promptly dispatched, all within the last thirty pages of this 600-page novel. ‘Cool!’ as Ryan would say. On the way, of course, Billy learns many valuable lessons about taking responsibility for oneself and so on – all the twentieth century psychological orthodoxy concerning the addictive personality.

Having passed through his well-documented, but somehow symbolic, ordeals, Billy marries one of several ‘pleasant-looking’(but otherwise faceless) women ‘about his own age’ whom he has met during the course of the action, adopts Ryan, resumes his legal practice, and they all live, inevitably, happily ever after.

Just in case we doubt its authenticity, however, Courtenay finishes the novel with the death of a minor character from a heroin overdose. This is a masterly touch of pathos. She is a blues singer, the daughter of an indigenous man and an Irish woman. After her funeral, her father stands on Billy’s harbour-side balcony and sings Billie Holiday’s ‘Strange Fruit’. It is hard not to feel that this girl has been little more than a token sacrifice to realism.

The role in this story of Matthew Flinders and his cat is hard to explain. Billy has a long-standing sentimental attachment to Trim, which is what prompts Ryan to strike up a conversation with him in the first place. Billy recounts the story of Trim for Ryan throughout the novel, partly because the boy seems interested and partly as a form of literary therapy. Being an atheist, he rather ludicrously chooses Trim as his ‘higher power’ for the purposes of his AA programme. I admit, though, that any deep symbolic connection eludes me. There is a genial artlessness about this book that will no doubt endear it to many, while others will find its prolixity and sentimentality hard to swallow.

Comments powered by CComment