- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Bob Ellis is the quintessential Labour groupie, and Goodbye Babylon the latest instalment in the saga of his love affair with the ALP, which began with The Things We Did Last Summer, a slim and evocative volume, published twenty years ago. By contrast, Goodbye Babylon is a fat book; rather like Ellis himself, it is sprawling, dishevelled, undisciplined but likeable, witty, and gregarious. His prose, though prone to excess, can be rich and compelling.

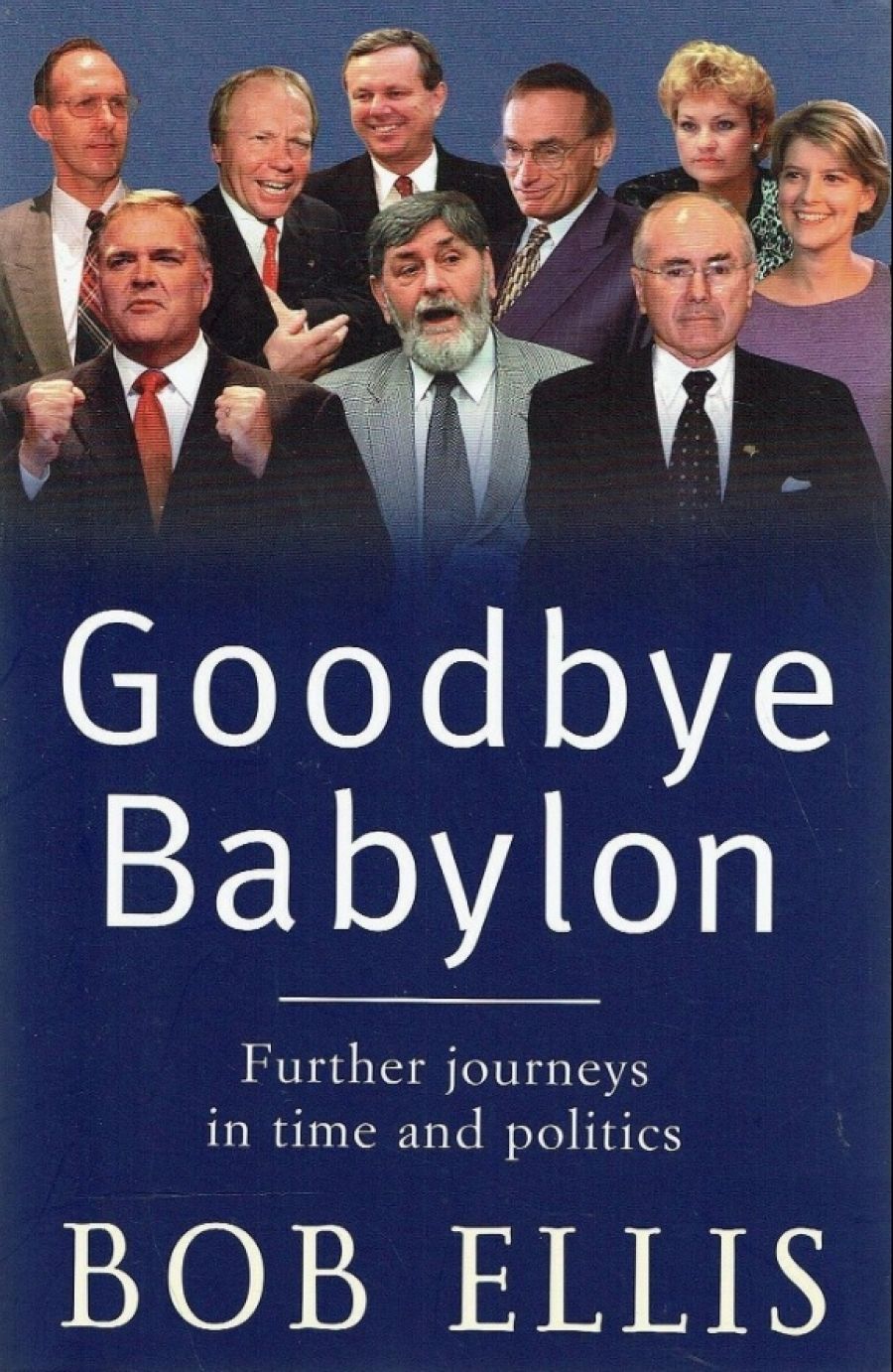

- Book 1 Title: Goodbye Babylon

- Book 1 Subtitle: Further journeys in time and politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Bob Ellis

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Qm4qz

The book’s main building blocks are notes and jottings apparently written at the time of the events. Although laced with hindsight, they give the narrative much of its immediacy and vividness. Since Ellis sees elections as the great dramas of the democratic process, fully half these entries deal with the thirteen election campaigns of the period. And, if this plethora of antipodean elections is insufficient, we get a savage, yet hilarious, study of dimpled chads, malfunctioning voting machines and butterfly ballots from the Florida farce that decided the US presidential election, plus a visit to Britain to report Tony Blair’s electoral triumph of 1997. Not that Ellis has much time for Britain’s wunderkind: ‘A shallow fast-moving fraud’ is one of the epithets applied to Britain’s Labour leader. Ellis provides us with a ringside seat for most of these elections, though, surprisingly, not one for his home state election in 1999, possibly because it was one of the few that failed to result in a change of government. But his remain ringside rather than inside views, for Ellis is a courtier, not a principal: one who scrambles for titbits at the king’s table; cadges taxi cab lifts with the mighty; uses his charm and gregariousness to infiltrate the discussions of princes; and scuttles into tally rooms and television studios in the wake of the great. What we get is little in the way of significant or authoritative new material; rather, a brilliant evocation of the mood and tempo of the times.

The one obvious exception to this is the detailed insider’s view we get of the bizarre negotiations between Mike Rann and the maverick Liberal Peter Lewis, which brought resolution to the South Australian election of 2002. Here, Ellis is an insider because of his intimate relationship with Rann. Even with Beazley, you always sense that Ellis is a bit player and, with Bob Carr, for all their easy familiarity, the master/retainer status is always evident. The proverbial shiver runs down Ellis’s spine when Carr, questioned as to his greatest self-indulgence, replies without hesitation, ‘Bob Ellis’. With Rann, it appears much more like a friendly partnership, a joshing relationship manifested on their trip to Israel in 1999.

There is, of course, much else in these jottings besides elections. National ALP conferences find him scurrying around the corridors of Wrest Point Hotel in Hobart observing the big beasts plotting, debating and playing. He buzzes around the Constitutional Convention of February 1998, presided over by Barry Jones and Ian Sinclair ‘like two old moth-eaten MGM lions, their roars majestically catarrhal, avuncular and final’. He chatters with the Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul, ‘[for] ten years ... the world’s greatest thinker’, basks in the ‘golden glare’ of Gore Vidal, ‘a true prince of letters and a monarch of the table, though he dressed, it was widely agreed, far worse than me’. Vidal has a lovely parting line in response to an Ellis query as to what he thought about Australia. ‘A good place,’ replied Vidal. ‘You do look after your needy. That old crippled couple, the Whitlams, for instance, down to their last cup of caviar. And how you care for them.’

Ellis is a regular presence at celebrity funerals – those of Don Dunstan and Richard Wherrett in this volume – and death inspires some of his best writing. He gets Dunstan exactly right, recognising him as a seminal figure: ‘Nine years before Wran, seventeen years before Hawke ... twenty-four years before Keating’, Dunstan set much of the radical agenda for late twentieth-century Australia. Nor is Ellis distracted by the personal glitter. ‘This was no dilettante in pink shorts. This was twenty-six years of hard slog in the (party)…This was a man who changed his country, not single handedly but by years of persuasive discussion, and changed it with a persistent eloquent selflessness for the good.’ Dunstan could ask for no better epitaph.

These notes on Dunstan illustrate Ellis’s ability to capture perceptively the essence of a personality. Beazley, ‘huge and shaggy like some returning battle-scarred Aslan’, is generously but fairly portrayed – ‘the statesman, and the decent man, beneath the lousy ties and untucked shirts’– but his strategic flaws, his inability to make his own luck and his ‘Micawberish voluminousness’ are recognised. Nevertheless, in these depressing days, many perhaps share Ellis’s conclusion that he was the best prime minister we ever had.

Like all courtiers, Ellis is something of a sycophant, flattering the powerful in the ALP, apart perhaps from Simon Crean, for whom Ellis seems to have a marked distaste. The incumbent leaders are a handsome lot with film-star qualities. Rann is a mixture of ‘Mickey Rooney and Tommy Steele with a dash of Bugs Bunny’ and, surprisingly, is ‘possibly (the) best-looking Labour leader now working’; Peter Beattie, ‘both looking and sounding like Jack Thompson [is] our most magnetic leader’; Claire Martin, ‘beautiful, cultured, thoughtful, [is] a sort of Top End Margaret Throsby’. In this company, the best Jim Bacon can do is to remind Ellis of ‘the moustached moose-faces of great dead French comedians’. But over Steve Bracks he positively drools: ‘His Levantine complexion olive, smooth and flawless [is] like that of a fifties film star (Edmund Purdom, Tyrone Power).’ What on earth, thought I, will he do with Bob Carr? But Ellis is equal to the challenge. On page 252, we learn of Carr’s ‘lean, Clark Kentish frame’. Others get the same Hollywood treatment: Natasha Stott Despoja is ‘the icy Hitchcock blonde’; Pauline Hanson ‘the down-market Kim Novak in Vertigo’; Kerry O’Brien ‘tawnily handsome as ever as Steve McQueen’.

No such star treatment, of course, for the Liberals, although Peter Reith is handled with surprising sympathy, Ellis speculating that he ‘had put on the mask of the cruel, fast-yapping hydrophobic professional as a career choice and played it well but never believed in it’. But such charity is rare. From the prime minister, with his ‘pink-faced pre-pubescent smirk’, down to Tony Abbott – ‘what an all-out, full-on crumb he is, unceasingly’ – to Richard Alston, with ‘his plaster shop-dummy’s face and his droid’s blue eyes’, the tone is venomous.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of padding. Satirical passages – ‘The Book of Bush’ and ‘The Forged Diary of John Howard’ – seem like clever efforts from Honi Soit, and Ellis’s verse has a similar undergraduate smartiness. The book is stuffed with quotations: three pages from that most quoted of unpublished novels, Bob Carr’s Titanic Forces; two pages of testimonials certifying that Bob Ellis is not a drunk; and copious quotations from the author’s favourite writers, ranging from Herodotus through Shakespeare to Ellis. Ellis uses repetitive quotations from poetry as a rhetorical device to bolster his prose. W.B. Yeats is the chief victim. His refrain, ‘Down, down, hammer them down/Down to the tune of O’Donnell Abu’, is quoted at least eight times. The most shop-soiled of all Yeats’s lines, ‘All changed, changed utterly/A terrible beauty is born’, is perhaps justifiable in relation to September 11, but there is no excuse for its further repetition. And then there is that ‘rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouch(ing) towards Bethlehem to be born’. This we get three times, though on one occasion the bloody beast goes astray and heads for Barcaldine

Ellis’s prose requires none of this bolstering and stuffing. The effect is to raise the frequently heard plaint, ‘Why does he go on so?’

Comments powered by CComment