- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

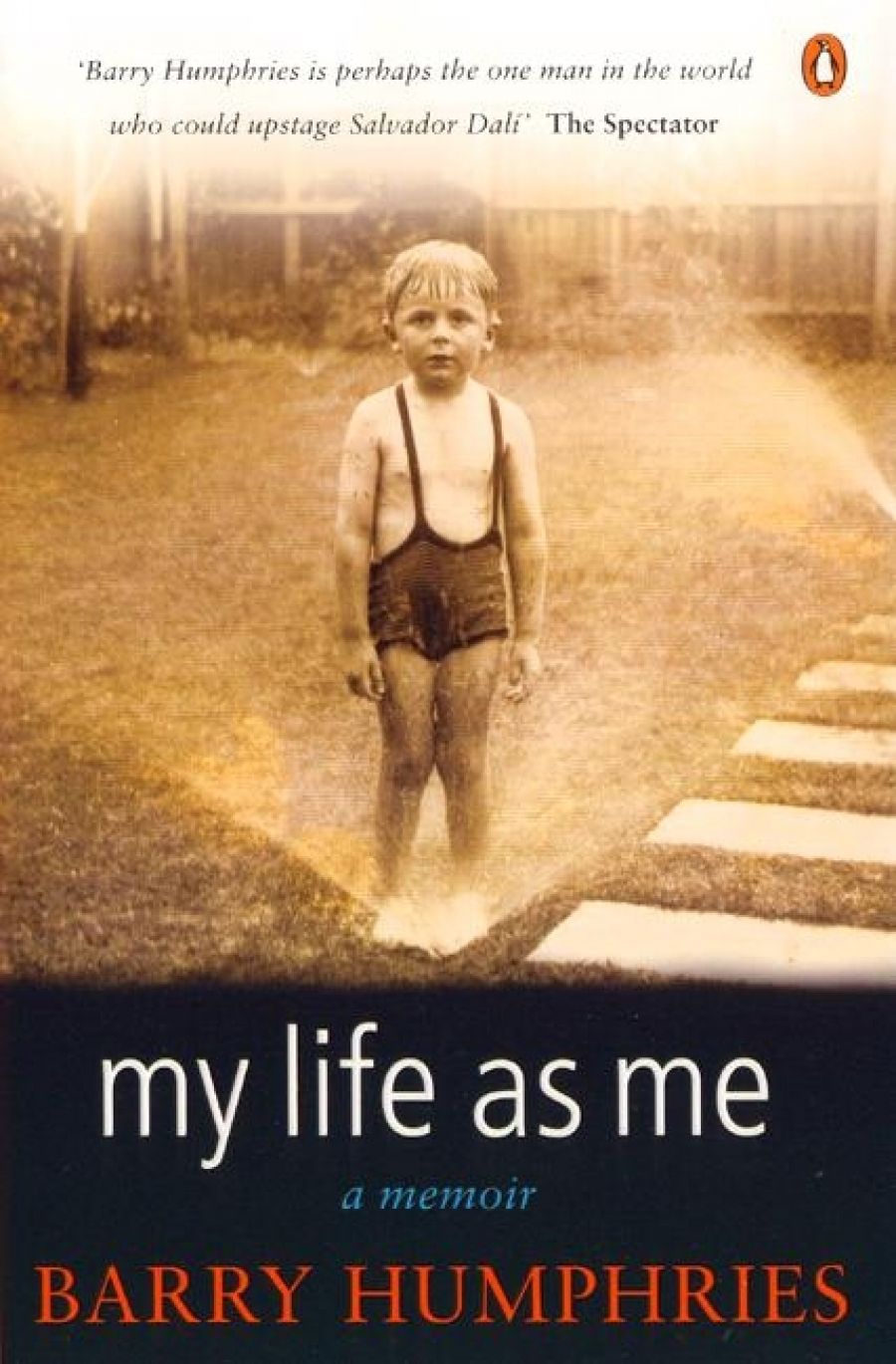

- Custom Article Title: Peter Rose reviews 'My Life As Me: A memoir' by Barry Humphries

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Barry Humphries published his first volume of autobiography, many readers were left wanting ‘More, please’ – avid as gladdie-waving victims during one of his shows; voracious as the greedy polymath himself ...

- Book 1 Title: My Life As Me

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $45 hb, 384 pp, 0670888346

Infancy is never far from Humphries’s consciousness. Nor is Christowel Street, Canterbury, where he grew up in one of the many houses his master builder-father erected in Melbourne’s ‘nicer’ suburbs. The book itself opens on a beach. His father, moustached like Melvyn Douglas, strides towards him, whistling. It is a sparkling morning and ‘Sunny Sam’, as Barry was called, knows he is adored. Then his mother chips in, wishing that his father would stop whistling.

Louisa Humphries may be one of the more ambiguous figures in Australian autobiography – a kind of maternal miscreation – but she emerges as the real star of this book, Protestantishly censorious to the last, but rather more complex than before – more interesting. We want to learn more about this brittle, snobbish, friendless woman. One day someone will write the biographies of Ruth White and Louisa Humphries, helping us to understand why our two greatest satirists loathed their mothers so, and fretted about them all their lives. Louisa’s old sayings are there in abundance, perfectly phrased. ‘Must you play all that continental music, Barry? It wasn’t that long ago we were at war with those people.’ One ‘slightly uncalled for’ entertainment prompts the immortal: ‘Well, at least we can say that we’ve seen it.’ When the precociously artistic Barry paints a Roman Catholic convent, Louisa chastises him: ‘Why can’t you paint something nice?’ Always he seems to hear that cheerless voice saying, ‘Stop drawing attention to yourself’ and ‘Remember you’re out!’

Intriguingly, we learn that Louisa once had a brief career as a comic performer in amateur theatricals, and was considered very funny. Humphries’s adolescent relationship with his mother seems to have been more complicated than Dame Edna’s spectacles. It was she who bought him expensive overseas art magazines, gave him an account at a picture framer, and paid for his life-drawing classes. Seriously spoilt, Humphries was allowed to purchase any book he desired. And yet, so frigid was Louisa’s manner he could never be certain of her approval and always doubted that he was unconditionally loved. Only in a crisis was her position unmistakable. In a moving anecdote, Louisa, determined to prevent her son from tearing on to a busy road on his runaway bicycle, steps into his path and takes the full weight of the hurtling bicycle, thus sustaining a permanent leg injury. ‘It was as if she was trying to tell me something else – something more complicated and more personal.’

A trying and improbable son, Humphries seems to have been more despondent than his arch jokes would have us believe. In ‘tortured adolescence’, he would sit outside his house waiting for his real parents to turn up and collect him. He thinks of parents as people ‘who turned down the volume on one’s life’, and admits that ever since he has been convalescing from ‘the long illness of youth’. When Barry’s university pranks and prodigious drinking inflame his parents, he endures the ultimate maternal reproach: ‘What a pity, Barry. You used to be so nice.’

Still, it was this mixture of rejection and provocation that fed the young Dadaist. Disgusted by the torpor of Melbourne’s ‘Tudoid’ suburbs, he set out to affront the captive burghers on their trams, in a series of infamous stunts. When he lured his fellow students into theatre spaces at Melbourne University, he found the courage to perpetrate his ‘puny acts of psychopathology’. As long ago as 1956, he depicted Alexander Horace ‘Sandy’ Stone in a short story and promptly animated him (if that’s possible) in a revue. Of his finest creation’s début, Humphries notes: ‘I croaked the rambling interior monologue with the intention of driving the audience mad with fatigue.’

Humphries is at his most acute when discussing his art. We learn about the genesis, and gradual apotheosis, of Dame Edna Everage, with whom, he insists, he has nothing in common, ‘except perhaps my legs’. His distrust of and near-contempt for his audience are profound. If a show is to work, this heterogeneous mob of strangers must become ‘one animal’. They must act in unison, ‘obedient to the will of the author and the performer’. Anyone who saw Sandy Stone’s one-man show in the 1990s will attest to the almost religious submission in the stalls. Humphries’s mastery of audiences, his admonitory humiliation of latecomers, are legendary – an essential part, as he says, of ‘the infantilising of the audience’.

In the late 1950s, after early theatrical successes and the first of his three failed marriages, Humphries went to London, where Peter Cook was instrumental in promoting his satirical career, with mixed success. Barry McKenzie was unleashed in Private Eye, and eventually in two films. Humphries is frank about his compulsive drinking and ultimate hospitalisation. The physical toll of his bohemian life makes the richness and longevity of his career seem even more formidable.

But the book flags in the middle, as if dampened by the hazily recollected sordor of his life in the 1960s. Here, the deliberately haphazard structure of the memoir (‘a cubist, even a futurist, self-portrait’) becomes too aimless for its own good. Humphries may have set out to eschew name-dropping in More Please, but it is ubiquitous in the new book. Why not, perhaps, for the names are interesting ones, but we are reminded too often that Stephen Spender became his fourth father-in-law, and the facsimile of Stephen Sondheim’s card on his sixtieth birthday is surely otiose. Why did Humphries need to tell us that Dr Kissinger loved his Broadway show (not, perhaps, something to advertise)?

The book regains its former brio when Humphries, rejuvenated because firmly on the wagon, goes back on the road in the 1970s. There is a brilliant cameo of one of Dame Edna’s early accompanists, Iris Mason. Humphries is mordant about the political correctness he encounters in the United States, and open about the tedium of long tours and his susceptibility to women. (‘Whenever I was alone like this, my first thought was always, Who can I be alone with?’) Scores are brutally settled, but then, what are scores for? The one about Princess Michael of Kent is choice. Only rarely does prudence temper his wit (three early wives escape lightly). Generally, the fearless temerity of Humphries’s writing is remarkable. Some names are fudged, but Humphries goes further than most Australian writers would dare. How circumscribed, how self-censoring, most contemporary memoirists seem by comparison, silenced by what James Joyce called ‘the choir of the just’.

Humphries’s diction remains ornate and dandyish – ‘a gallimaufry of marvels’. Leaves are luteous, consorts osseous, sheets positively reasty. We do not expect mistakes from Barry Humphries, so it is surprising to find Reynaldo Hahn’s and Carl Sandburg’s names misspelt. But the writing is as fine as ever. A girl’s thigh is ‘brailled by the sea’s chill’, a cheap hotel vividly captured in ‘the condemned chocolate on the pillow’. Some of the anecdotes, such as the one about Sumner Locke Elliott’s sad exit from Martin Road, are too familiar by now, and there is an uncalled-for story about Kingsley Amis falling down drunk at the Garrick. Others enrich the book, such as the one about the Jewish tailor and the overcoat, which is worthy of Guy de Maupassant.

There is a long and acute passage about Patrick White, ‘[o]f all complicated men … the most complicated’. While acknowledging the greatness and nobility of White’s novels, Humphries regrets his increasing need for flattery and sycophancy, and despises the curmudgeonly dismissal of old friends. Typically, Humphries cannot resist mentioning what the young visiting orgiast purportedly found in White’s bedroom cupboard.

At the end, after half a century of egregious escapades and an unrivalled body of work, Humphries relaxes into a new tenderness and acceptance. Doffing his hat in lifts, he reminds himself of his late father, as he does when he cautions his two young sons with his parents’ discouraging platitudes. Has he become Sandy Stone, he wonders. Finally, in a moment of unexpected atonement, he reaches back through the years to address his ‘dear parents’, audible and inescapable still.

Comments powered by CComment