- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Filling a Niche

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For several years, I have bemoaned the dearth of substantial, challenging Australian novels for ‘middle years’ readers. During a recent stint working in a specialist children’s bookshop, I was frequently asked by parents of these readers – upper primary, lower secondary – for ‘books that will last longer than an afternoon’. I was hard-pressed to find many recent Australian titles that would fit the bill. Two new novels by first-time writers aiming both to entertain and challenge their audience with complex yet accessible stories, concepts and language go a small way towards filling this gap.

- Book 1 Title: Walking Naked

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $16.95 pb, 171 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

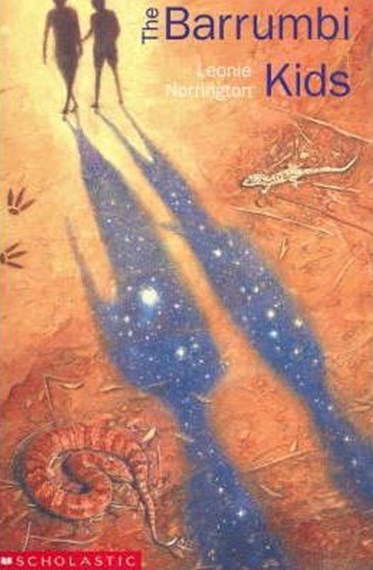

- Book 2 Title: The Barrumbi Kids

- Book 2 Biblio: Scholastic, $16.95 pb, 197 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

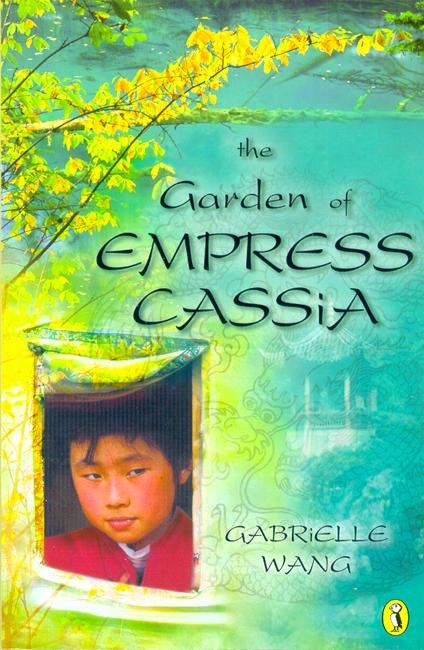

- Book 3 Title: The Garden of Empress Cassia

- Book 3 Biblio: Penguin, $14.95 pb, 98 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Set in a remote Northern Territory community, Leonie Norrington’s The Barrumbi Kids is a remarkably assured and accomplished first novel. It tells the story of a year in the lives of Tomias and Dale, and of their families and the Long Hole community. Dale, whose grandfather was the first white man to settle in Long Hole, and Aboriginal Tomias are in Year seven. It’s their last year before heading off to boarding school, and these boys are going to make the most of it. The novel is more or less a series of connected vignettes that take us through the seasons of the North. Through these stories – hunting wallaby and goanna, wagging school, battling grassfires, liberating chickens and sorting out the local bully – Norrington builds a wholly unsentimental, but incredibly vivid and affectionate, sense of place and community.

Norrington has a wonderful skill with language and characters, black and white, who speak a distinctive Aboriginal English that reflects their approach to life: pragmatic, unpolished and uniquely poetic. Language (Aboriginal) is incorporated into the text mostly without explanation – there’s a glossary at the end of the novel, but context nearly always renders the words meaningful. Here is Mavis, Tomias’s mother, explaining to Lizzie, Dale’s sister, how to deal with a crocodile:

‘If he come. Look at him hard. Make that face like you gonna kill him.’ Her face is fierce. ‘Not gammon – properly. Call him ginga. Ginga.’ She whispers the name under her breath like a chant. ‘Look at him hard. He listen you call his name, he’ll know you not frighten for him. You subbie?’

This chapter, where Lizzie does indeed stare down a crocodile about to attack her, is one of the most enthralling in the novel, and demonstrates Norrington’s ability to shift the focus between characters. While Dale and Tomias are the ‘main’ characters, certain scenes and events are told from the point of view of others in the community. It’s an unusual technique for a children’s novel, and it’s rare that shifting perspective works as effectively as it does here. Norrington is a gifted author, and The Barrumbi Kids makes an important contribution to Australian literature for young readers.

Gabrielle Wang’s fantasy novel, The Garden of the Empress Cassia, while not entirely successful, is still an impressive début. Mimi feels left out at school. She’s picked on and teased by the other kids, especially Gemma, leader of the cool group, about the smells from Mimi’s father’s traditional Chinese medicine practice. She wonders what life would have been like had she been born in China instead of being a ‘banana’: yellow on the outside, white on the inside. Mimi is only really happy when she’s drawing, but her father wants her to concentrate on her academic studies. When he goes away to be with his dying brother, Mimi has the opportunity to use the beautiful Empress Cassia pastels – and that’s when the magic begins. When people come to admire the beautiful drawings Mimi does on the footpath outside her house, she discovers that the worlds she draws take on a life of their own.

The Garden of the Empress Cassia has some significant flaws. The mechanics of the fantasy are glossed over too much for the novel to be entirely satisfying, and the ending is a little abrupt, with important issues around Gemma the bully left unresolved. Where it succeeds best is in the characterisation of Mimi and the depiction of her growing friendship with Josh, which nicely counterbalances the bullying and racism Mimi encounters. The fantasy of the magic pastels also affords Wang an opportunity to explore the healing powers of art, and the need to remain true to yourself and your gift. Young readers will find much to enjoy in the novel.

Young adult readers are well served by Australian authors, and one of the brightest new voices for this age group is Alyssa Brugman. Brugman’s first novel, Finding Grace, was an honour book in the 2002 Children’s Book Council of Australia awards, and has found favour with the young adult and adult market alike. Like Finding Grace, the great strength of Brugman’s second novel, Walking Naked, is the power and integrity of the narrator’s voice. Megan is second-in-command of the in-group; those girls found in most high schools who do well academically, charm the teachers and make the lives of the outsiders and nobodies in the school community sheer misery.

The novel opens with Megan horrified to find herself in afternoon detention, stuck there with the girl they call The Freak – which is in fact preferable to her actual name, Perdita Wiguiggan. The Freak is the in-group’s favourite target. They don’t actually know anything about her, of course, just the hearsay – she’s a witch, she smells, she’s crazy. In due course, entirely against her will, Megan finds herself not only getting to know, but almost getting to like, The Freak – or at least grudgingly to admire her. And so for Megan, hanging on to her position as second-in-command of the in-group by the skin of her perfectly orthodontised teeth, this is where the trouble really begins.

We’ve met girls like Megan and her cronies in a dozen Hollywood teen movies, where the mismatched relationships are usually romantic. In Walking Naked, Brugman taps the richer vein of complicated female friendships. Perdita, it turns out, is very smart, appealingly cynical and challenges Megan in unexpected ways, cocooned as she is by her loving parents and the in-group. Ultimately, as you would expect, Megan has to choose between Perdita and her other friends, and the consequences are devastating.

Brugman is a gifted novelist, but Walking Naked was spoiled for me by its ending, dealing with the consequences of Megan’s choice, that is too obviously signalled right at the book’s start. I knew what was going to happen, was distracted by how Brugman would get her characters there, and remained mostly unmoved by what should have been a deeply emotional reading experience. Teenage readers may not have this problem, as they read in different ways from adults. It’s possible, even likely, that young readers will be entirely engaged by the depiction of friendships and schoolyard politics; nevertheless, for this reader, the overt and premature flagging of the climax is an unfortunate flaw in an otherwise enjoyable read.

Comments powered by CComment