- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The author as shoehorn

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

We’re all interested in people; misanthropy is not trendy. Contemporary interest in people may be manifested by the success of reality television, the media coverage given to celebrities, and books such as these, which set out to investigate people and what makes them tick.

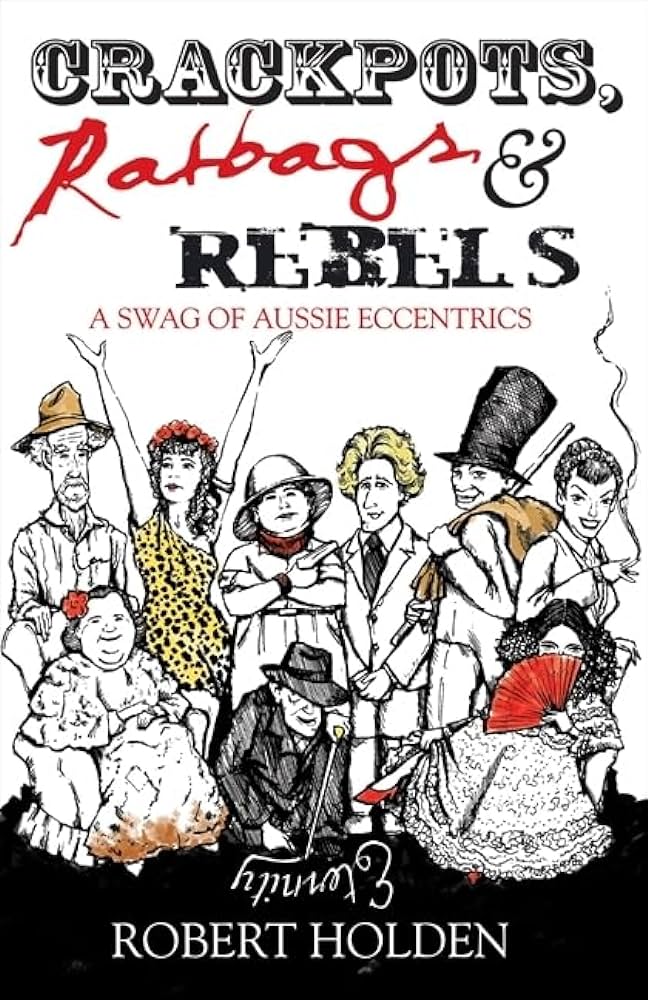

- Book 1 Title: Crackpots, Ratbags and Rebels

- Book 1 Subtitle: A swag of Aussie eccentrics

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $29.95 pb, 240 pp, 0733315410

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

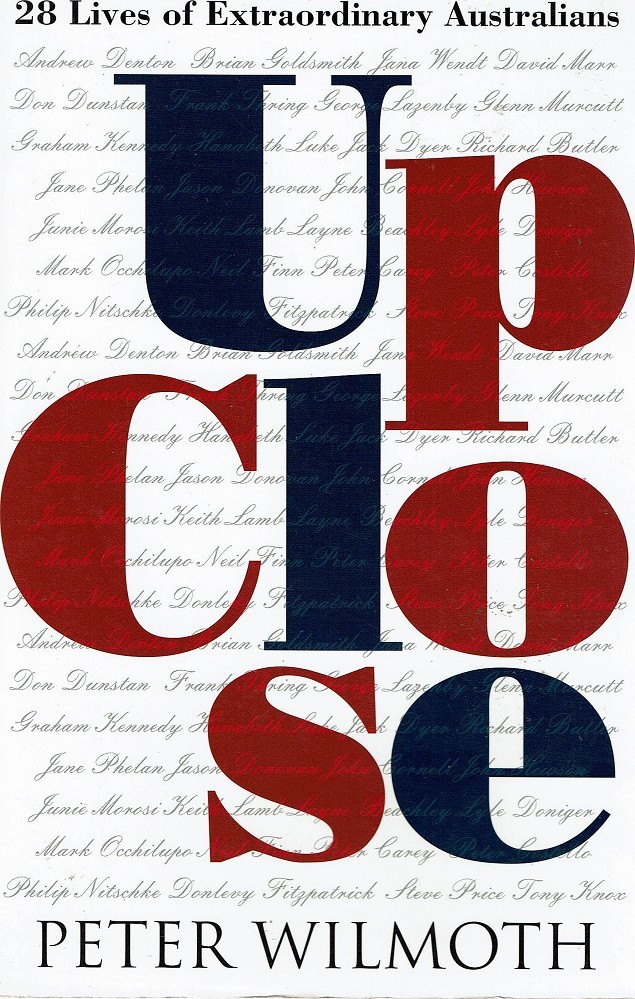

- Book 2 Title: Up Close

- Book 2 Subtitle: 28 lives of extraordinary Australians

- Book 2 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, $30 pb, 313 pp, 1405036575

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The disappointment of Crackpots, however, lies not in slips such as these but in its failure to engage imaginatively with the subjects of its condensed biographies. There are too many of them, and they are too sparsely researched. Holden observes them from the outside: he does not imagine why they were as they were or what their lives consisted of, because he is too ready to settle for the picturesque and the superficial at the expense of the stuff of humanity. He fails to engage with his rich material, cramming too much into too little space and giving insufficient thought to distinctions or connections that might have illuminated his claims. His unfortunate reference to ‘pettifogging research’ reinforces the impression that he hasn’t worked very hard at any of it.

Paradoxically, once you decide to label a number of people as eccentric, blithely packing them into the same category, you ignore the considerable differences between them, even when those differences are the original criteria for your choice of subjects. Having classified people too easily, Holden appears to seek only the characteristics that support his criteria, running the risk of not noticing other, possibly more significant, traits. Thus I find it disconcerting to see Alfred Deakin (a significant figure in our history) lined up alongside colourful personalities such as Billy Blue and Bea Miles. Holden’s disinclination to dig deep is nowhere better exemplified than in his treatment of Deakin, for whose story he appears to have consulted only John La Nauze – not a good choice when your chief interest lies in Australia’s second prime minister’s fascination with spiritualism. It would have paid Holden rich dividends to check John Rickard or Al Gabay, both of whom are more willing than La Nauze to examine Deakin’s spiritualist leanings. He might have obtained insights that would have enabled him to give a more sensitive and balanced portrait. But that, I suppose, would have gone against the grain of the collection, whose general mood is high-spirited and cavalier. Rather than arguing or persuading, Holden habitually asserts – with exasperating confidence – that his readers will agree with his assumptions and conclusions.

Part of the challenge of a book about people is to burrow inside one’s subjects, to show them in a new and preferably interesting light. Wilmoth describes himself, in the preface to Up Close, as ‘shoe-horning someone’s life onto a page, to a deadline’. This is no easy task, and a quick glance at the contents page did not raise my hopes. But there is much in Up Close that is fascinating, even for grumps and misanthropes. Wilmoth has the advantage over Holden in that he has been able to speak with, and listen to, his subjects; and he has the skill and perception to use this advantage. The studies largely depend on interviews; but Wilmoth is assiduous in chasing friends and associates in order to illuminate aspects of his subjects that prove difficult to draw out by interview alone. The result, at its best, gives us studies of scope and dimension. Sometimes he finds it impossible to achieve closeness with his subject, as with Frank Thring, so instead of a revelatory interview, he provides an hilarious account of a vintage eccentric refusing to play ball.

The collection spans the years from 1993 to 2004 but is not arranged chronologically. The effect is to make us feel as if we are peeking through a succession of unexpected and sometimes quirky windows in time: the immediacy of conversation is juxtaposed against the ironies of history. Junie Morosi, for instance, interviewed in 1996, has moved on from her perceived notoriety and reminisces about it equably. Andrew Denton speaks wistfully in 1997 of his desire one day to have a national interview programme. Peter Costello, six years later, is careful not to speak wistfully or otherwise of a different ambition.

This collection warns against stereotyping: famous people don’t necessarily have interesting things to say, but there is no reason to assume they won’t, either. Layne Beachley, who was adopted, speaks movingly and unsentimentally about her meeting with her biological mother. Entrepreneur Brian Goldsmith struggles with cancer, rock star Keith Lamb with schizophrenia. Gently, persistently, Wilmoth shoehorns away, persuading people to tell their tales, seeking what he describes as ‘the mask down, the unguarded comment’. More often than not, he succeeds. I won’t say I entirely changed my mind about media celebrities, but there’s more variety in this book than appears at first to be the case. There are perceptive accounts of survivors who have confronted the darkest, hardest things in life: Hanabeth Luke, who lived through the bombing at Bali; Lyle Doniger, who endured six years in Bangkok’s Klong Prem Prison; Tony Knox, who is trying to find his way past the death of his partner Mietta O’Donnell. And a lighter touch is evident too: John Hewson confesses to a sneaking admiration for Paul Keating, who made his life such hell (‘He set out to tag me and he tagged me reasonably well’); Noeline Brown describes Graham Kennedy’s nicotine addiction (‘it was as though Kennedy were smoking for the Olympics’); and Jack Dyer lauds the loyalty of Richmond fans (‘I said, “I think I’ve killed this feller”, and a Richmond man said, “Don’t worry about that, it’s only manslaughter. I’ll get you off for nothin’.”’)

One hazard with a book like this is taking people at their own estimation, which, understandably, is frequently high. Wilmoth suggests this danger in his preface (‘You work with the words that come out of the subject’s mouth’), but all the same he is at times perhaps less astringent, or even wry, than he might have been. I am not quite sure that all his subjects can indeed lay claim to being ‘extraordinary Australians’; and the prevailing flavour is a mite too bland for my taste. I guess libel must be a danger in this walk of life; too caustic a tang might warn off potential subjects. Perversely, I found myself rather admiring Frank Thring for making his inner self so inaccessible. Certain others might have profited from similar restraint.

Comments powered by CComment