- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fragrance of contemplation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

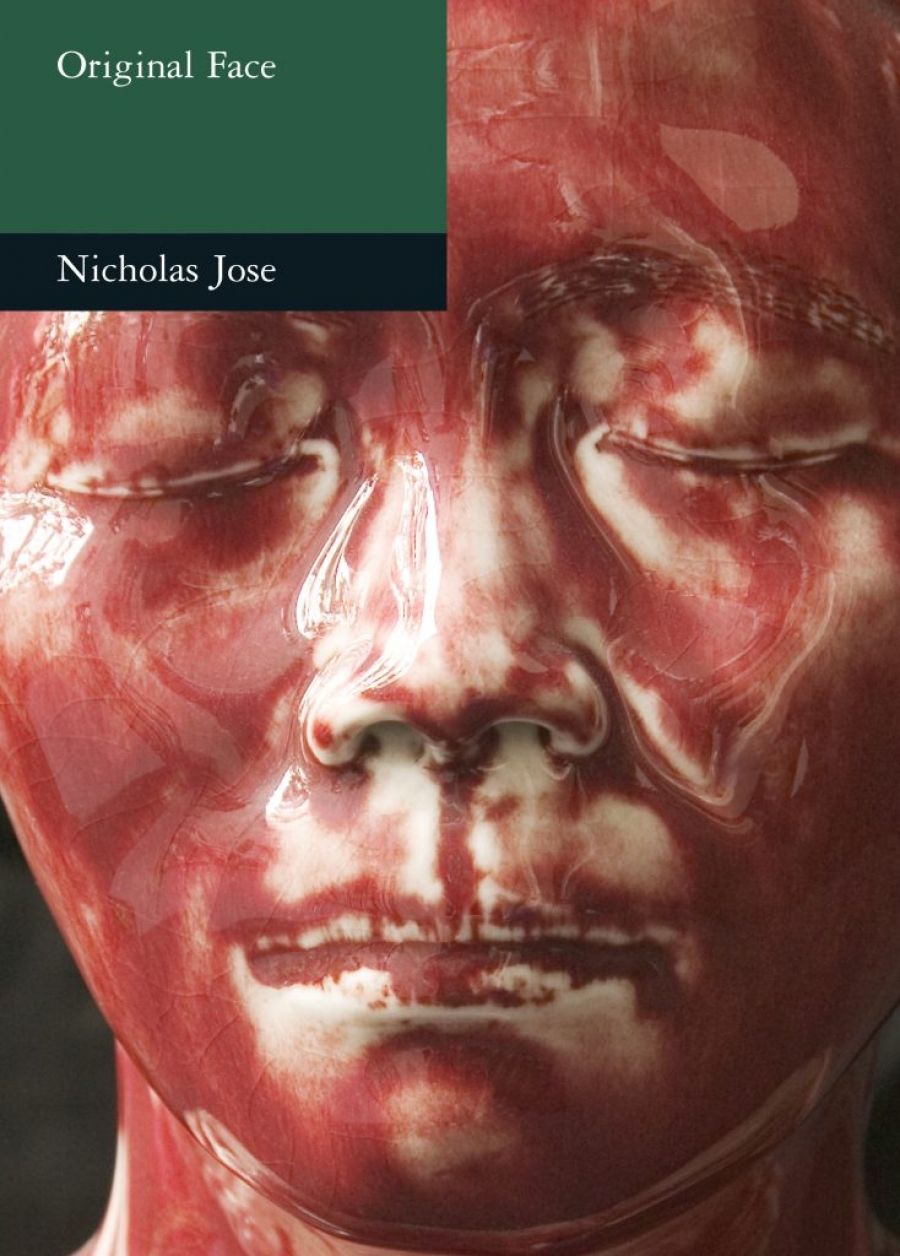

Nicholas Jose’s new novel, Original Face, begins violently. On the first page, a man is – expertly, and with a small knife – skinned alive, his face removed. We are in Sydney and the assassin’s name is Daozi, which in Chinese means knife. Jose’s seventh work of fiction traces the sometimes-brittle nature of identity as it plays with an ancient Chinese riddle: ‘Before your father and mother were born, what was your original face?’ It’s a confidently crafted pastiche; a kind of film-noir literature with a tender twist of Buddhist philosophy.

- Book 1 Title: Original Face

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $27.95pb, 308pp, 1920882138

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Lewis Lin, originally from Beijing, is a taxi driver, a ‘refugee of Tiananmen’, and is innocently caught in the detail of the crime when a sleek black car nearly runs him off the road. For the first half of the book, his ‘silver floating swan’ of a cab brings one central character to the next, stirring Lewis tighter into the mixing bowl of the plot. He’s often a step ahead of the police, though answers for him are less about justice than something more ambiguous; old memories are awakened.

Reg, his first passenger, is from the former Yugoslavia, and carries a kind of politically induced fearfulness with which the inquisitive Lewis can empathise: ‘a fear of power when it was backed up by a brute force blind to fairness of justice.’ Jasmine is a pretty, possibly duplicitous woman from Hangzhau, near Shanghai; ‘indeed a southern beauty’, thinks Lewis. Her recent arrival in Australia has something to do with a shared past with the murdered man. For help she goes to Bernie, a once successful, almost washed-up, cinematographer.

Like a camera lens, the language subtly adjusts with the third-person omniscient narrator’s gaze, to align with each character (which is most rewarding, later, when we’re introduced to the hazy floral world of a prominent painter). The cinematic imagery, though, is first sharpened through Bernie’s eyes: ‘Looking through the lens he saw only what needed to be seen. The jacaranda from next door, for example, billowing across the balcony in a cloudy scatter of mauve as he opened the shutters and stepped out into the day.’ In another scene, the villain points his knife and is caught, suddenly, in the careful description of light and shadow, his image slanting along the footpath.

Short chapters, too, enhance the cinematic aesthetic and create the effect of a swipe cut as we move between scenes. And the language swerves again, to the scent of a flower, something orange, a prickly seat, then, on the next page, a mango.

Eventually, a delightfully sweet pair of cops is on the case: ‘Ginger – for the bloodnut hair – Rogers’, a kind-hearted, slow-witted vegetarian, who tries his best to keep up with Shelley Swert, his fit, intuitive tae kwon do-obsessed partner (or sidekick). They meet at the Chinese restaurant ‘The Golden Dragon’ to shuffle clues that lead them to an immigration racket, and to keep them from the power-hungry chief Ronnie Silverton.

Did I mention the zither player? Just when the novel is about to flutter into something quite stylised, Jose shows great skill in maintaining the colour and humour, without straying from serious themes and tones. The sifting of clues ¾ the markers of the thriller or film-noir genre ¾ becomes a metaphor for the slipperiness of identity and how it hinges on the smallest moments: glances, even. You get a sense that the novel could go on forever unravelling the case, making new connections, following new leads, the characters opening and closing doors to themselves.

Jose’s well-received third novel, Avenue of Eternal Peace (1989), was set just before the Tiananmen Square massacre. You’ll notice that, sixteen years later, he’s listening for the shock waves. One of the darker characters, Ah Mo, has found that his early passion for justice has spiralled into something confusing. Lewis, perhaps, has not forgotten things so successfully, either. Jose is observing the life of the Chinese Australian, and the customs and obligations that colour a new life in Sydney.

Hints of sentiment – an unlikely coincidence or two, and some flowery sentences – will be forgiven by most readers because Jose is always in control of the genre-play. I’m still deciding whether the dénouement fell short of the high expectations set up by what came before it, though, towards the end, when many of the characters come together for a meal late in the book, the images and colours and names – Garlic Shoot, Jasmine, Shelley, Ginger – pique the senses, and there’s a uniquely therapeutic sensation of the characters eating their way through the novel, so that they themselves can move on. Original Face is a delicious read, with a fragrance of contemplation that follows the reader around after the book has been closed.

Comments powered by CComment