- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Essential unity

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Early in Carolyn Leach-Paholski’s The Grasshopper Shoe, a maverick artisan named Wei argues that ‘all form strives to the enclosed and therefore piques our curiosity. What lies open or does not have a hidden side could be counted as formless. All that remains unjoined, the line which does not seek the satisfaction of unity in the circle, all this to aesthetics is dead.’ These words could be interpreted as the novel’s declaration of formal intent. Indeed, both of these début novels are concerned with beauty and perfection, in the sense that they seek to convey emotional and philosophical intensity through rich poetic language. The use of ornate metaphors and imagery in prose has its risks. It requires skill and a good deal of restraint to allow the narrative enough air to breathe so that the novel’s momentum is not stifled.

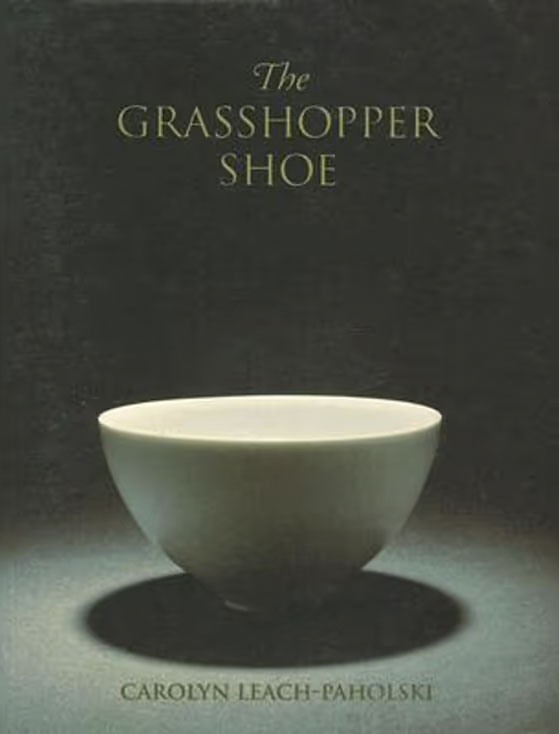

- Book 1 Title: The Grasshopper Shoe

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $29.95pb, 405pp, 1740561405

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: A New Map of the Universe

- Book 2 Biblio: University of Western Australia Press, $24.95pb, 248pp, 1920694552

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Leach-Paholski, who is an established poet, negotiates this potential difficulty with ease. The Grasshopper Shoe is an exceptionally well-written first novel. Set in nineteenth-century China, it is about the relationship between Hsiao Yen, a Chinese woman, and Lucien Battard, a French naturalist. Hsiao Yen, the only daughter of Xi, a wealthy porcelain collector, is born with six fingers on her right hand. As a result, her father shelters her from the superstition and cruelty such a deformity would attract in the outside world. She grows up behind the walls of her father’s estate, while Xi educates her in painting, geography, natural history and philosophy. She is sharp-witted and imaginative, keen to learn all she can. Her particular fascination lies in collecting and categorising objects: ‘She collected hair ornaments, tufts of dry grass, metal pins. She had mosses and bones. She had the scat of two types of lizard, fly dirt and the coughed pellet of an owl.’ Her motivation is aesthetic. She loves to look at her treasures and to arrange them, loving them for their inherent beauty no matter how broken or commonplace or dung-like they seem to others.

Lucien Battard is, by contrast, a devout Catholic, a naturalist and a scientific artist. He travels to China on a mission to single-handedly vanquish Darwin’s theory of evolution; Battard is determined to gather a collection of flora and fauna impressive enough in its diversity to prove the presence of God’s hand in nature. But his scientist’s instinct for physical proof as a stamp of legitimacy is in opposition to his absolute faith in God.

Leach-Paholski is interested in this clash between religious faith and scientific empiricism. As Battard and Hsiao Yen discover an affinity in their shared passion for the natural world, they enjoy long discussions during which Hsiao Yen questions Battard’s faith. She is puzzled and slightly repulsed by his belief in the dominion of man over beast and by his casual brutality when it comes to capturing and dissecting specimens for study. She challenges the idea that a god that can be so indifferent to human suffering could be considered benevolent. Battard clings to his faith, however, even though it undermines his credibility as a rational scientist.

Beyond this intellectual conflict, the novel evokes a host of interesting themes that are of contemporary relevance. There is a subtle analysis of differences in cultural perception, especially when it comes to spiritual beliefs and artistic representation. When Hsiao Yen initiates Battard into her childhood study of the songs of cicadas and crickets, their divergent beliefs meet in a common interest. His attitude is at first superior and aloof. He sees the collection of insects, graded by the tone of their song, as being the opposite of scientific research and thus a waste of time. Yet the diligence of Hsiao Yen’s aesthetic method, her attention to detail and her immense knowledge of the differences between various species seduce him. ‘The mechanics of Hsiao Yen’s labours,’ writes Leach-Paholski, ‘had the reality and fascination for him of a world mirrored, transposed, as a reflection has the attraction of truth subtly altered.’ He is soon absorbed in the task of recording the trills, chirps and hums of their tiny choir. Colour, pattern and sound become the guideposts for their endeavour, rather than the scientific categories of anatomy or physiology. Battard’s impulse to measure and analyse is synthesised with Hsiao Yen’s equally rigorous, but utterly different, methodology.

The philosophical oppositions in this impressive novel are never truly resolved. It goes on to open up several new thematic fronts, examining the nature of modernity and the role that psychoanalysis has played in reshaping perceptions of human nature. Yet the unity of the imagery, and its intellectual energy, give The Grasshopper Shoe the illusion of smoothness. The novel’s essence is represented in the symbolism of an incident that occurs just before Hsiao Yen leaves her father’s house to be married. Her dowry includes the Grasshopper Shoe, an exquisite and very valuable porcelain bowl. Xi and Hsiao Yen have caught a large carp and place it in the bowl as a talisman to accompany the bride on her journey. The fish is transported with clumps of pondweed, water snails and silt. This earthy grit and writhing life contained in a delicate, man-made object is analogous to Leach-Paholski’s achievement. Her novel does not shy away from the messy contradictions of the human condition – illness and convalescence; intellect and faith; love and grief – yet at all times she retains control, exhibiting an exceptional purity of form.

A New Map of the Universe, which was written by Annabel Smith as part of her PhD in creative writing at Edith Cowan University, is less consistent. It, too, strives to attain emotional and intellectual heft by employing extended metaphors. The main character, Grace, is a reluctant architect who is asked by her lover to design a house for him. This is a symbolic as well as a practical concern. The task of creating a space is emblematic of Grace’s struggle with feelings of inadequacy and her ambivalence about her past.

It begins with the first flickers of romance between Grace and Michael, who meet on a darkened balcony at a party. Michael is an anthropologist whose work involves collecting the myths about the constellations. He seduces Grace with a culturally varied array of stories about the stars. They embark on an intense love affair, which is interrupted when Michael departs for a study trip overseas.

Smith works hard to establish Grace’s character in two central narratives about her parents’ childhoods and how they came to meet. These set pieces are easily the strongest parts of the novel and are written with a sensitivity to time and place. They establish the emotional cornerstones for Grace’s character. She has grown up with none of the usual family anecdotes and ephemera. Her architect father died of a heart attack as they played together in the park when she was a small child. Her mother has never emerged from her grief, often treating Grace with savage cruelty.

Emotion is the force that propels this novel forward. The intensity of Grace’s unexpected union with Michael triggers a need to unearth the roots of her discontent and fear by examining the family stories that have been hidden from her. It is a shame then that Smith sometimes mistakes cliché for profundity, especially in the sections of the novel that depict Grace and Michael’s relationship. At key moments, the novel lapses into indulgent, quasi-mystical storytelling that infantilises Grace’s character. This seems ill-advised in a novel supposedly about a young woman’s emergence into a long overdue psychological maturity. The work would have possessed far more emotional power had Grace’s inner turmoil been conveyed with greater restraint.

Comments powered by CComment