- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Crusaders and vandals

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If Melbourne’s claim to be the ‘world’s most liveable city’ can be taken seriously, it is largely because of its capacity for reinvention, the adaptability of its buildings and infrastructure to an expanding population, and changes in transport, communications, patterns of work, and the general lifestyle of its inhabitants.

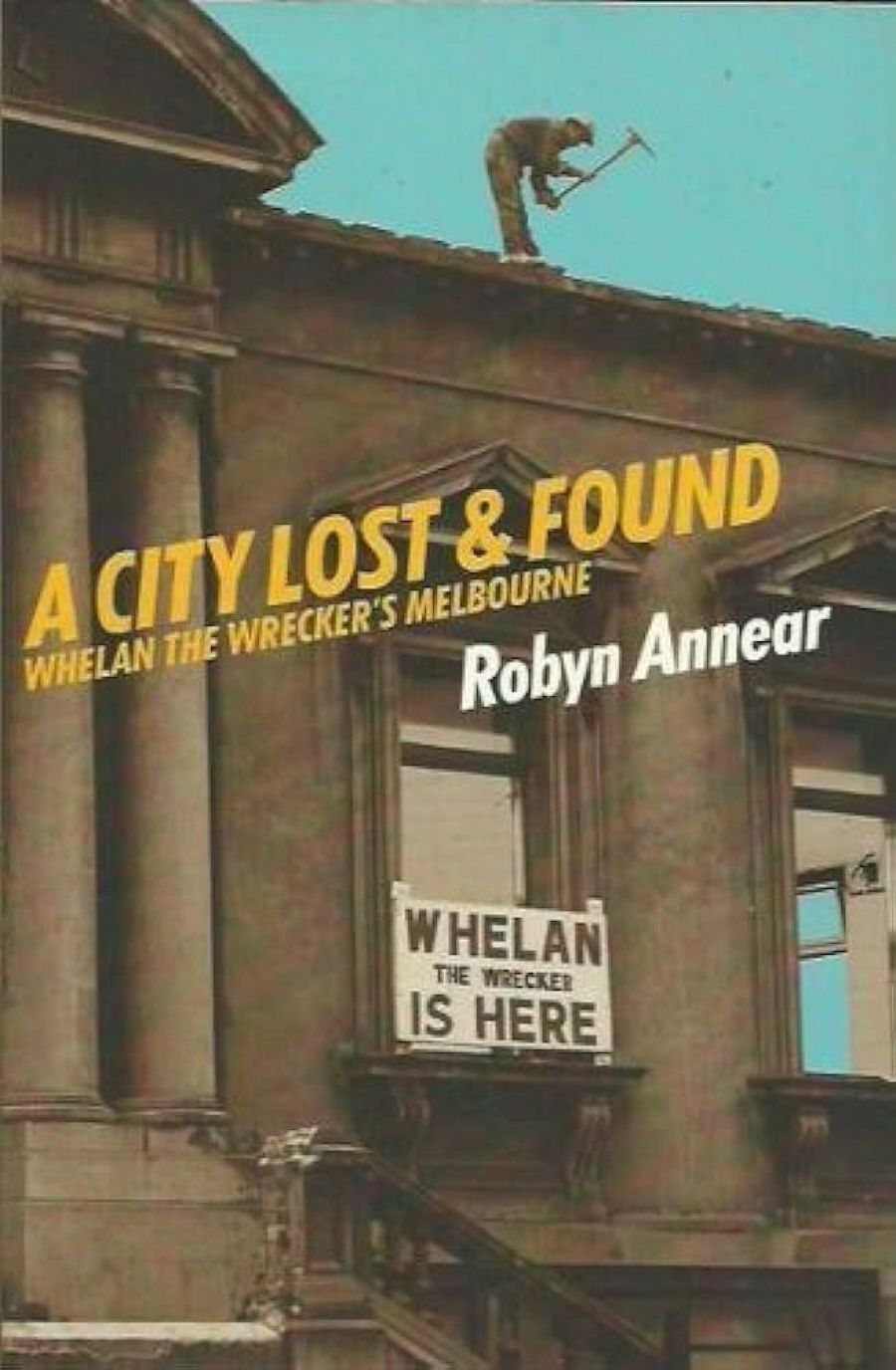

- Book 1 Title: A City Lost and Found

- Book 1 Subtitle: Whelan the Wrecker's Melbourne

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.95 pb, 310 pp, 1863953892

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Jim Whelan began as a timber merchant in booming 1880s Melbourne. As the over-elaborate finances of the boom began to crumble, whole suburbs emptied. Ruined developers walked away from unfinished projects. Whelan began paying for the privilege of salvaging reusable materials from the wreckage. That is the first important point, easily missed by those of us who have been programmed to see wreckers as vandals: demolition is dangerous and expensive work, and salvaging material from the site is often an essential part of the wrecker’s business plan. The best wreckers – and the Whelans were Melbourne’s best – have as deep a knowledge of materials and construction techniques as the finest architects. To pull something apart and reuse the pieces, you need first to understand how it was assembled.

Few of Melbourne’s major buildings have lasted more than a couple of generations, and the most obvious exceptions (the State Library, for example) have gone through multiple redevelopments. Commercial buildings are particularly vulnerable: in my search for 1890s photographer Charles Bristow Walker, I found a restaurant on the site of his Fitzroy studio, a petrol station on the site of his Carlton studio, and Nauru House where he had his city studio. Frustrating for the researcher, but not necessarily a bad thing for society at large: do you really want to live or work in an unrenovated nineteenth-century photographer’s studio? Trying to keep everything is as wrong-headed as throwing it all away.

The Melbourne University campus on the northern edge of the city became – after Whelan’s yard – the major refuge, or dumping ground, for cast-off statues and other fragments of dismantled buildings: the original commerce building had the façade of a demolished city bank slapped onto it; the nameless goddess from the Equitable Building occupies a grassy knoll near the Baillieu Library; Ogg’s Collins Street verandah graces the entrance to University House, and on the list goes. In the late 1990s the university administration was inspired by a ‘crusade’ (the scheme really was called that by its promoters) to restore the gothic splendour of its first buildings. In this case, demolition cleared the site not for something new but for something old. Removal of the twentieth-century brick extension to ‘Gothic North’ restored the façade, to general acclaim – until the full implications emerged. The original building contained no plumbing, a deliberate strategy on the part of the founders to stall the enrolment of female students. So an already overcrowded campus acquired the luxury of an unusable building. Not, perhaps, quite the outcome the architectural crusaders had in mind.

The villains of Annear’s tale are mostly architects. When news broke of the imminent demolition of St Patrick’s Hall (among other things, the meeting hall for Victoria’s first parliament in 1851), the site architects, panicking that their project might be blocked by heritage considerations, telephoned the wreckers and demanded that they ‘get in and do as much damage as you can before anyone wakes up’.

Architectural hubris marked both the beginning and the end of the 132-foot Equitable Building. Completed in 1896, it cost thousands of pounds (many millions in today’s money) and twelve lives: two men died at the quarry, three shipping the stone to Melbourne, and seven more (including a passer-by) at the building site itself. The base storeys and entrance portico alone contained 1700 tonnes of granite. The keystone of the majestic, four-storey entrance arch – rising twenty metres above the street – weighed fifteen tonnes. It was ‘built to last fifteen wars and ten centuries’, but outlived its usefulness within a few decades. By the 1950s the cavernous halls of the original building (the first floor was on a level with the third floor of its neighbours) had become ‘a terrible waste of space’. For once, the National Trust was onside: ‘Americanised Renaissance’, they sniffed, ‘interesting, but not worthy of preservation’. When the demolition was approved in 1960, the Melbourne City Council privately predicted ‘at least three fatalities’. There were several near misses, but the only serious injury to the Whelans was financial: after the sale of salvage from the site, they lost some £30,000 on the job; the building was so solid that it took almost as long to demolish as it had to construct.

The major frustration with this wonderful book is that it lacks references or any kind of reading list apart from the picture credits; so following up Annear’s stories demands inspired guesswork. The first edition of Bearbrass was frustrating in a similar way: it had no index because Annear didn’t see it as ‘that kind of book’. But of course it was – and the new edition is all the better for being indexed. Perhaps Annear didn’t see A City Lost and Found as that sort of book, either, despite having completed it under a State Library of Victoria fellowship; or perhaps the publisher was afraid of looking too ‘academic’ for a popular audience. Either way, let’s hope for a change of heart, and a second edition.

Comments powered by CComment