- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tyranny of the tape recorder

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As an unknown young artist, Margaret Olley gained instant fame as the subject of the enchanting portrait by William Dobell that won the Archibald Prize in 1948. With Olley’s Mona Lisa smile, the warm, summery colours of her dress and her extravagantly flower-laden hat, Dobell created an enduring image. An embarrassed Olley did not welcome the publicity. This was not the way she wanted to enter the world of art. ‘I also paint,’ she told reporters defensively. Today, her vibrant interiors and still lifes have made her famous in her own right.

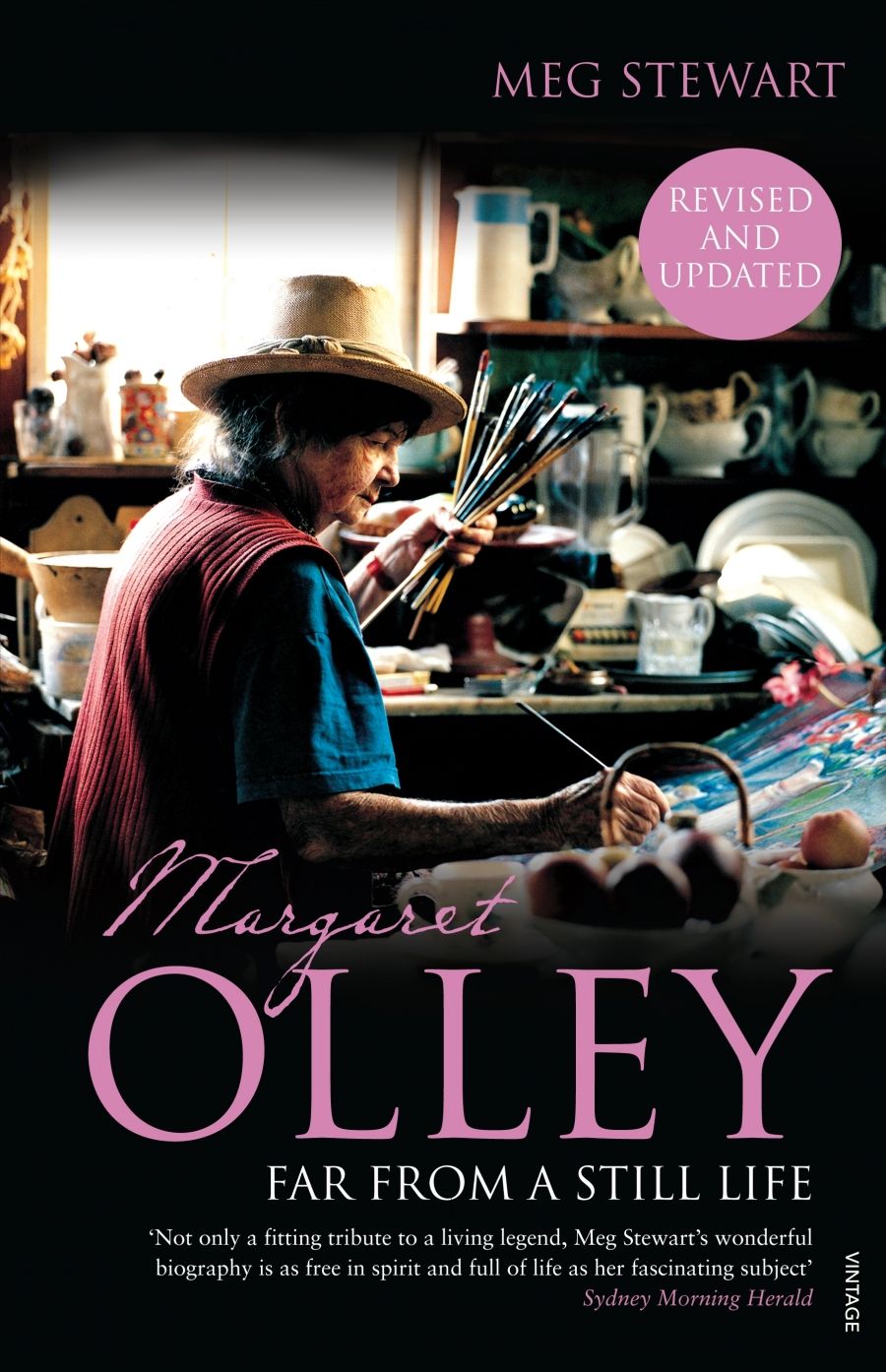

- Book 1 Title: Margaret Olley

- Book 1 Subtitle: Far from a still life

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $49.95 hb, 584 pp, 1740513142

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Margaret Olley: Far from a Still Life, by Meg Stewart, chronicles the artist’s crowded times. Stewart is best known for her memoir of her mother, the Sydney painter Margaret Coen, published in 1985. Written in the first person, and titled Autobiography of My Mother, it evoked time and place with subtlety and skill; and gave Coen a voice and a point of view. In Margaret Olley, Stewart revisits the world of art in Sydney in which she herself grew up, as the daughter of Coen and the poet Douglas Stewart.

The biography opens with vivid glimpses of Olley’s North Queensland and of the 1930s Brisbane of her schooldays. Here, Stewart’s independent research works well, but her narrative becomes cluttered when Olley’s tape-recorded voice inexorably takes over. Just as Stewart’s book on her mother was a biography in disguise, this comes close to autobiography. In blurring the genre line, Stewart has given such large tracts of her text to Olley’s first-person voice that her own status as author is all but abdicated. Half a page or more in italics, signalling Olley’s words, may be followed by Stewart’s paraphrase or background information before Olley resumes her own story. Olley’s words sometimes outnumber Stewart’s by as much as six to one. Confusingly, quoted material from anyone other than Olley is not italicised. Biographies sometimes suffer from the tyranny of the footnote, but, as John Thompson has said, ‘the tyranny of the tape recorder’ is an equal risk. Although it should be an advantage that Olley has talked frankly and freely to her biographer, the result here is a largely unmediated flow, too long at 506 pages of text.

There is a good story – indeed, there are many stories – to be excavated here by the patient reader. These include the artist’s childhood, lovingly recalled, her discovery of herself as artist, her place in the Sydney art world, her travels in Europe, her love affairs, her alcoholism and her buoyant old age, in which her still-life paintings still hold their charm.

Olley recounts her close friendship – ‘almost a love affair’ – with Donald Friend. In 1953, in a time of despondency about failed affairs with other men, Friend wrote in his diary: ‘I must marry or burn. Burn up either with solitude, or with excesses of promiscuity that rise from loneliness.’ He thought of Olley as the one woman he could trust. Two years later, after an abortion, in a panic about her own life and lovers, Olley proposed marriage to Friend. He refused: ‘If Olley and I were of an age when passion is spent, we would be happy together, but as we both now are lively and sensual natures, such a marriage (in view of my own peculiarities) would be a pretence … I only wish this were not so.’ The friendship survived. Both Friend’s diaries and Olley’s recorded memories recount their time together at his Hill End house and during many companionable painting expeditions.

The impetus for this biography, Olley says, came from her discovery that Friend’s account of their relationship would appear in the third volume of his Diaries, published by the National Library in 2005, and reviewed in the October issue of ABR. She decided to give her own version, which includes a ‘fumbling’ sexual advance from Friend, which he did not record. His bitter old age, in the fourth volume, may give more reasons for Olley’s pre-emptive strike.

Olley stresses her need for independence. In a revealing passage, she says that her relationship with gallery manager and theatre director Sam Hughes was ‘absolutely perfect because he came and went all the time … I could never have dreamt of having someone underfoot all the time. Somebody underfoot is an abomination.’ She lived with Hughes in Paddington from about 1973 until his death in 1982.

In all Olley’s comings and goings, between Europe and Sydney, Brisbane and Bali, and her activities in the real estate market, the essential thread of her career as an artist sometimes gets lost. There are candid accounts of her drinking, her recourse to AA, and her recent bout of depression. It would be good to have more reflection from Stewart on the ways in which Olley’s talent and her need to paint have shaped her life, but her voice is drowned in Olley’s copious, genial flow.

Comments powered by CComment