- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A desert rover

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Here is an entry in one of A.D. Hope’s notebooks: it is from 1961: ‘Ingenious devices for letting in the light without allowing you to see out, such as modern techniques provide – e.g., glass brick walls, crinkle-glass, sanded glass and so on – remind me very much of most present-day forms of education.’ This is a representative passage from the notebooks. Lucid itself, it bears on elements of frustration or nullification in experience. As such, it testifies to Hope’s recurrent sense that human beings can easily mislocate their ingenuity, with results that are both memorable and regrettable. In a later notebook, in 1978, speaking of the labyrinth as a model of human life, he writes: ‘Looking back one sees that comparatively trivial blind choices have often determined one’s course and that the majority of people do end up in blind alleys.’ One might contest the generalisation, but will not easily forget the analogy.

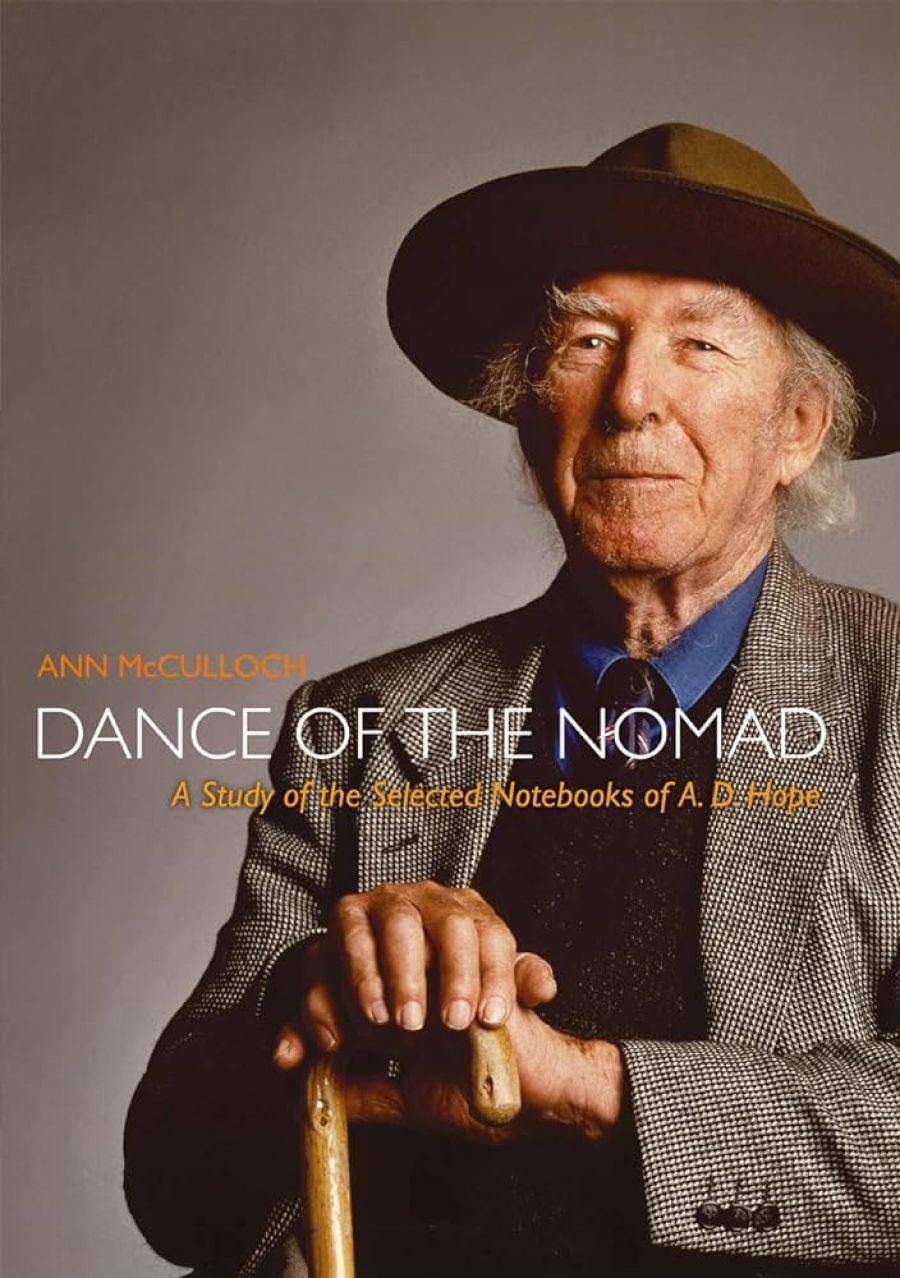

- Book 1 Title: Dance of the Nomad

- Book 1 Subtitle: A study of the selected notebooks of A.D. Hope

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $45 pb, 397 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

So the first thing I would notice in this selection from the notebooks is a vigour in Hope’s seeking out of comparisons. By some accounts, this habit of mind is highly appropriate for a poet – as in Aristotle’s ‘to be a master of metaphor is the greatest thing by far’. If so, Hope abundantly fulfilled his lifelong ambition to think and write ‘poetically’ – and not only in the poems. As the human hand, by courtesy of the opposable thumb, can move in more than one plane simultaneously, so the human mind moves in more than one ‘plane’ when it sees the point of a joke, or makes a metaphor, or asks a question. Much of Hope’s writing, whether in prose or in verse, can be seen as a flexing of that kind of mind.

‘The chief thing,’ he writes, ‘is to move easily and with assurance in one’s territory of language. Its range and extent do not matter, provided one has made it one’s own.’ It is easy to imagine W.H. Auden saying this, and the sentiment is no more lackadaisical in Hope than it would have been in Auden. To move with that ease, that assurance, is a master’s aspiration, not a loafer’s. In one philosophical tradition, much stress is laid on the mind’s dynamic ability at combining and distinguishing notions, with judgment being the crowning accomplishment. Hope writes as someone who is aware that ease and assurance of movement over the linguistic terrain is something to be attained only through constant, and sometimes elaborate, intellectual and imaginative exercise. The notebooks themselves are part of that exercise.

Still, he does want to give the palm to poetry. Thinking about Dryden’s reference to ‘the other harmony of prose’, Hope applauds this way of putting it, and acknowledges that ‘prose can be used and manipulated in many ways which the sharp metrical and syntactical form of verse will not allow. But if verse is more limited by its superior order it is capable, by virtue of that order, of a brilliance and an impact that prose will never reach.’ There would be those who would take issue with the requirement of a ‘sharp metrical and syntactical form’ in poetry, but Hope would never have bothered to give them the back of his hand. Personally courteous, on occasion courtly, he could on paper prod writers he found distasteful onto a plank into nowhere.

A mild example of this is his remarking, after a meeting with F.R. Leavis, that ‘Perhaps the most interesting thing … was the experience of confronting a mind operating only on a “literary” level – nothing above or below the world of books – a shape of the complete monomania that art always tends to become.’ Whatever of Leavis, Hope’s own bookishness was not confined to the makers of literature, or its commentators. A leafing through Dance of the Nomad would turn up reflections on cosmology, on the fortunes and the misfortunes of sexuality, on dreams and their possible roles, on the character of the senses, on ecology, on mythology, on psychology. I suspect that in the notebooks of many a writer some such interests would find at least passing expression, though often enough as wedges of information or of affirmation. In Hope’s case, they are usually there as stimuli for further reflection. In 1954, after quoting a passage in which Hazlitt is musing on the relationship between poetry and power, Hope says, ‘Superficially what nonsense this is; and how deeply and seriously true.’ In 1981, after quoting from Jung, he says, ‘I see now that I have probably misunderstood Jung. I had better get to know him.’ Not bad for a 74-year-old.

Hope wanted above all to be thought of as a poet, though he feared that his criticism might outlive his poetry – surely a needless fear nowadays, when Theory’s maw engulfs both enterprises indifferently, like so much krill. In 1977 he writes, ‘I dare say that if Jesus Christ were alive today the Who’s Who would list him as “Prophet and Carpenter”!’ Readers of Hope’s poetry will be aware of how vehemently, and memorably, he could assail those whom he regarded as inept critics, and he must have found a lot of enjoyment in wielding now the flail, and now the scalpel. But what may have nourished him most, apart from writing the poetry, was thinking about that practice. He reports, for instance:

There are nearly always three poems involved in the writing of one. There is the poem I first see in my mind often in considerable detail and with all its tone, metre, shape, and so on fairly well defined. There is the poem I actually write, often quite different and nearly always emerging with a different ‘tone’ from that I first saw for it. And then there is the ghost of another possible poem on the same subject which nearly always suggests itself at some stage of the writing. But the poem actually written stands in the way and makes it impossible to realize this third poem at all.

Why is it that poets so rarely use the device of ‘variations on a theme’ so usual with composers?

Apart from other considerations, this insight might flag for us the important element of improvisation, not only in the achieving of works of art, but in the conduct of human life at large. One need not be a devotee of chaos theory, or any other enthusiast of the random, to acknowledge that (in the words of a nineteenth-century agnostic wit), ‘as luck would have it, Providence was on our side’. In all such formulations, there is a degree of sapience lodged at the heart of the irony.

Hope was never one for the programmatic, though he always cared about coherence – and his being a carer, passionate somewhat after Yeats’s kind, emerges clearly from this selection of his notebooks, which is arranged, introduced and explained very usefully by Ann McCulloch, who has already shed light on Hope’s path. Having known him a little and admired him a lot, I am glad to have the benefit of this intelligently conceived volume. I am aware, too, that what we have here is also, in effect, an introduction to further rooms in his labyrinth.

As McCulloch makes clear, Hope delighted to think of himself as nomadic, as unbiddable by those who would have him settle into accustomed paths. Paradoxically, this aspiration may be just about the most common among modern poets of any ambition, and accordingly Hope can be seen as a desert rover who is keen nonetheless to stay keyed to those cruising satellites which will both endorse and orientate his impulses. I doubt whether he would have minded this complication, either: he knew perfectly well that there are strategies for the accommodation of irony, and he knew which Muse presided over the process.

Comments powered by CComment