- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: From a small island, messages in a bottle floating out to sea. That was Gwen Harwood’s image for the poems she sent out during her early years in Tasmania, long before she had due recognition. Her letters, by contrast, knew their destination; they were treasured for decades by her friends, and they now make up the remarkable collection A Steady Storm of Correspondence ...

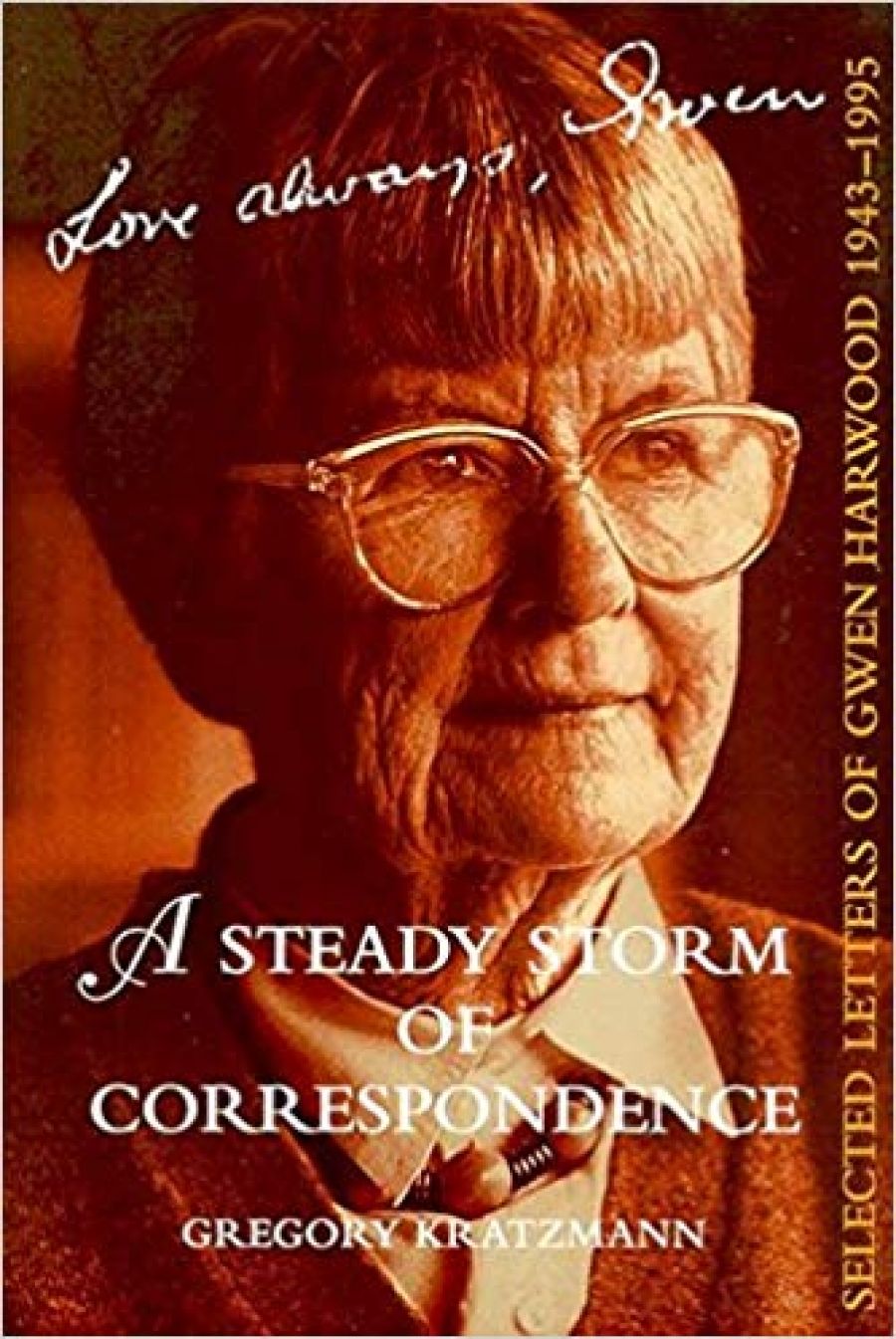

- Book 1 Title: A Steady Storm of Correspondence

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected Letters of Gwen Harwood 1943–1995

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $40 pb, 528 pp, 9780702232572

Through Riddell, Gwen met his friend Bill Harwood, an Arts graduate from Melbourne University. They were married in September 1945, just before Bill took up an appointment as a lecturer in the English Department at the University of Tasmania, where he spent the whole of his professional life. Because no letters to him were made available, Bill Harwood remains a remote figure. Some of his dry one-liners are quoted in scenes from family life; and their children are described with love and exasperation, pride and amusement. One letter sums up: ‘Children are better than the best poems, but poems are good too.’ The next, written as school holidays begin, savours the last day of solitude for writing before ‘the children start eating me alive’.

The lack of family letters does not mean lack of intimacy. Gwen Harwood’s friendships were remarkable in depth and closeness; to write letters was, for her, as natural and essential an act as to breathe. She had a collector’s eye for the absurd, and she made the most of the small ceremonies of Hobart life, sending to her mainland friends lethal accounts of parties given by the imperious wife of the vice-chancellor or the dismal proceedings of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. She also used the letter as others might use conversation: she wrote about music and poetry and religious faith and doubt; and she would often describe one friend to another. For their first fifteen years in Tasmania, the Harwoods had no telephone, and in the small circles of Hobart there were few to sustain Gwen’s need for intellectual companionship, or her sense of herself as a poet.

In the 1950s, with four small children to raise on a small income, Harwood could easily have been extinguished by domesticity. ‘Poor Gwen, your life is one long rush,’ her mother (never tactful) remarked. Not to be ‘poor Gwen’ took immense physical and emotional strength. Often she felt that she hated Hobart. ‘There’s something about getting up in the cold darkness and cutting school lunches that saps my living spirit. I often wish we had never come to this freezing island,’ she wrote in 1961. The mainland seemed a distant place from which came rejection slips: the little magazines, Meanjin in particular, were unwelcoming. They might keep a poem for a year and then return it. If they published, they might forget to pay, and the letters from editors gave only a meagre response: the thinnest gruel for someone who needed nourishment.

The first breakthrough came with a visit from Alec Hope. At first, it was a disappointment. Eager to talk about the new American poets, Harwood was irritated by Hope’s vagueness; she wondered what, if anything, he had read. ‘I had expected so much and had to be content with crumbs.’ But she had made a stronger impression than she knew. Back in Canberra, Hope wrote in warm appreciation, suggesting that she publish a volume of her poems. Tremulous with excitement, she sat down to write this news to Tony Riddell and found that she was trying to insert a sheet of paper into her sewing machine.

Even more important was James McAuley, who joined the English Department at the University of Tasmania in 1961. Initially, Gwen was wary: he had not shown much interest in her poems. But a firm and lasting friendship developed. ‘It is lovely having Jim in Hobart: he is like Wittgenstein in that he communicates something quite beyond what he says: his personal radiance can never be conveyed in words.’

McAuley and the younger poet Vivian Smith helped to reconcile Harwood to life in Hobart. Other important friendships thrived on the exchange of letters. Forty years on, it’s a shock to be reminded of what a small and closely intertwined group defined Australian poetry. Harwood’s friendship with Vincent Buckley produced some splendid letters. She was never sure that she completely understood ‘Irish Darling’ (her name for Buckley) and, in letters to other friends, she puzzled over the contradictions. Other poets, Chris Wallace- Crabbe (to whom Harwood wrote some exuberant letter-poems), Philip Martin, Tom Shapcott, and Norman Talbot became her much loved friends, as did Buckley.

One important group of letters centres on Harwood’s Bulletin hoax. Not as celebrated as the Ern Malley affair, it raised some of the same questions about literary judgment. In 1961, Harwood sent two sonnets to the Bulletin, using the pseudonym Walter Lehmann. Read as acrostics, they spelled out the messages: ‘So long Bulletin’ and ‘Fuck all editors’. As soon as the Bulletin editor published them, Buckley broke the story. In the ensuing publicity (‘Tas. Housewife in Hoax of the Year’), Harwood felt that her point was not understood. The poems were ‘poetical rubbish and show up the incompetence of anyone who publishes them’.

As well as Walter Lehmann, Harwood created W.W. Hagendoor (an anagram of her own name), Francis Geyer, Timothy Kline (Tiny Tim) and Miriam Stone. With the cooperation of friends on the mainland who provided postbox addresses, she introduced these shadowy personages, with their fake biographies, to unsuspecting editors. Although she enjoyed the mischief, it was bitter to discover that the phantoms’ poems were welcomed whereas those under her own name had been turned away. ‘I rankle at [Geyer’s] easy success of course – what’s he got that I haven’t except his name?’

To read four hundred Harwood letters within three or four days might sound like an endurance test. In fact, I found it pure pleasure. The letters reveal a many-sided personality. Harwood wrote brilliant comic set-pieces drawn from her daily round. She presents herself as a character: ‘little Gwennie’, a dear little housewife, an innocent abroad. She also touches the depths, in illness, in sharing the sadness of friends, and in the courage and grace with which she faced her own death. Her poetry was central to her being, but she sometimes rebelled against it. ‘It is to me a hateful talent. I cannot bury it. I would rather have been happy … I wish I could be cored like an apple.’

With the task of editing such densely allusive letters, Kratzmann has chosen to annotate lightly. This may be because full annotation would have meant a huge (and hugely expensive) volume. To place the reader, he has divided the letters into five time spans and preceded each sequence with a perceptive biographical essay. Even with this welcome contextual help, I would have liked more endnotes and, for future generations, some events and issues (the Orr case, for example) will need them. If any Australian poet deserves a Collected Letters, it’s Harwood; and Kratzmann, her chosen biographer, would be the ideal editor.

One poignant note in early and later letters is the wish to see Europe. Harwood loved maps (‘the names [of German cities] fill me with longing’). ‘I don’t think my spirit will reach its full stature until I have seen Italy,’ she wrote in 1957. And years later: ‘ONE DAY I WILL SEE THE TURNERS IN THE TATE AND MY BRAIN WILL EXPLODE.’ She never saw Italy, or the Turners. Her children grew up and left home: still she stayed in Tasmania, with occasional visits to the mainland. It seems a sad deprivation. But her poems and these letters show how she made her island world an everywhere.

Comments powered by CComment