- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

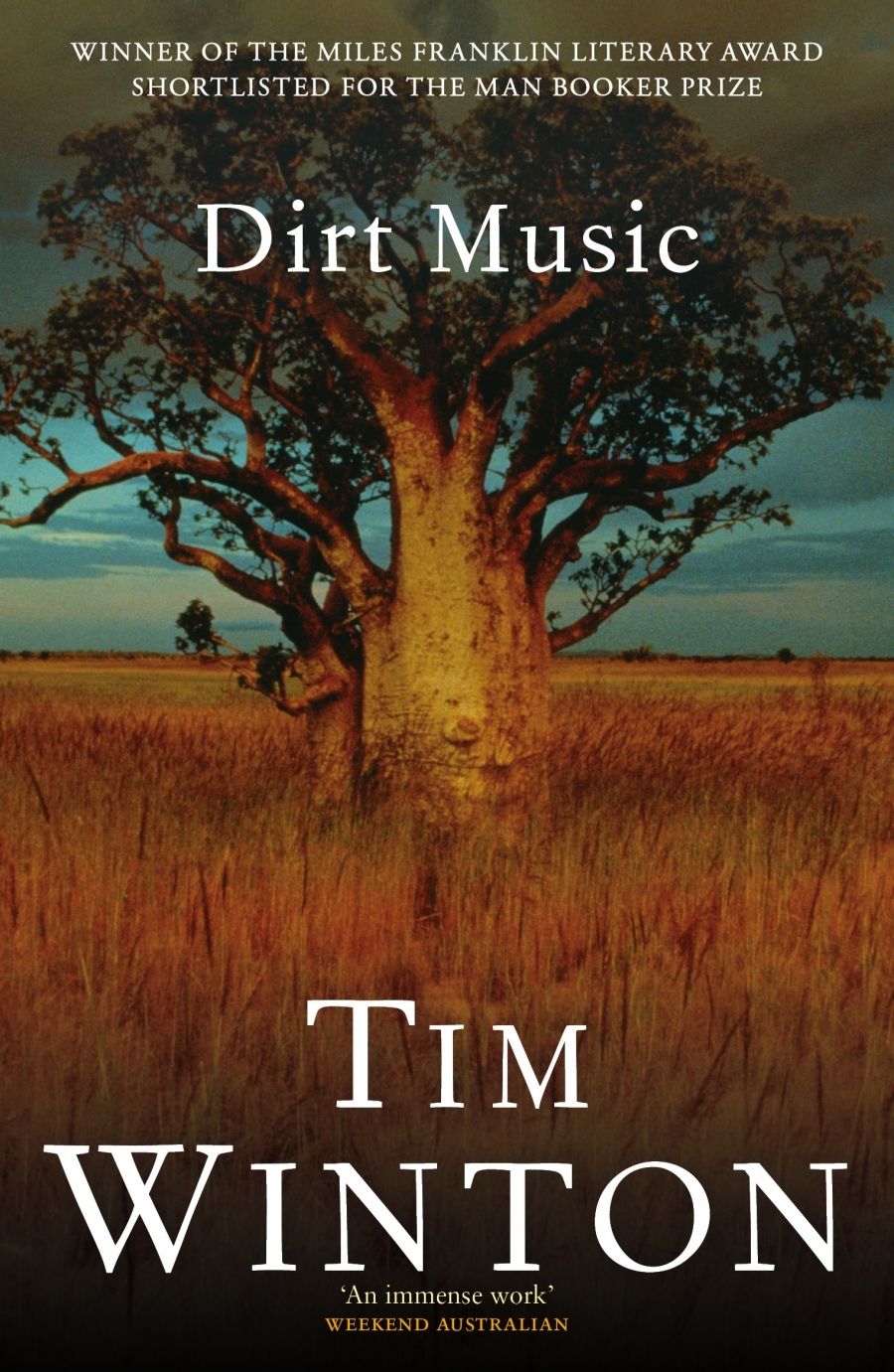

- Custom Article Title: Brian McFarlane reviews 'Dirt Music' by Tim Winton

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Talk about unlikely associations. My first response to the opening chapter of Tim Winton’s latest novel was how its sense of a life at a standstill, awaiting some new impulse, reminded me of Jane Austen’s Emma. Winton’s protagonist, Georgie Jutland, with a string of unsatisfactory relationships behind her ...

- Book 1 Title: Dirt Music

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $45 hb, 461 pp, 0330363239

And while invoking cinema, it is worth noting that the book’s narrative procedures seem to owe something to film. The converging courses of the two principals — Georgie and the local fish poacher, Luther Fox – are gradually unravelled through a series of short chapters, often no more than a page, that feel like bits from a cinematic montage of alternating lives. Further, the way each drifts between dream and reality (and Winton has remarkable skill in evoking the texture of dream, at once utterly real and impossible – see Georgie’s shipboard dream of her past on page 416) and, even more significantly, between present and past exhibits a fluidity that recalls the screen’s mobility in representations of time and place.

Winton dubs the coastal fishing shanty town a ‘personality junkyard’ and articulates this characterisation at several levels. There are minor characters like Rachel, the former social sciences graduate (‘married to a bloody drug baron,’ she wisecracks) who warily befriends the dislocated Georgie after massaging her spine; and the fat-gutted Beaver, who has a vaguely criminal past, buys a Vietnamese wife, and runs the local video store. (Jim, surprisingly, is working his way through its run of Bette Davis classics.) These hint at how people, in varying degrees undone, have settled among the nouveau riche who have made a fortune out of crayfishing and are trying unsuccessfully to forget their crude origins. The place is evoked with both sensuous and social accuracy: it may seem welded by a community of purpose, but Winton does not sentimentalise its capacity for malice and cruelty, for sheer meanness of spirit.

But, on another level, Georgie, her current fisherman partner, Jim, and Lu Fox each incarnate an individual personality junkyard, and each is a product of a tattered past. They are what they are at least in part because of their rancorous and/or painful dealings with their parents, with a past that has junked a good deal of what might have been best in them. Georgie comes from a well-to-do Perth suburb and private school, the bloody-minded one among a quartet of daughters to an adulterous QC father and a frilly, ultra-feminine mother who has lived for shopping and dies during the book’s time span, leaving Georgie with a lot of unfinished emotional business. There’s also been a traumatic experience in a Saudi Arabian hospital with a woman consumed by cancer. Georgie, back in Australia with no strong ties, has moved in with the taciturn Jim and his two teenage sons, in whom the motif of strained parent–child relations is set to be continued, their mother having died of cancer.

Jim is looked up to in White Point. His word is law/lore about anything to do with the fishing trade; he seems, at first, a decent enough man, if too unyielding to relate in any supple, profound way with Georgie, or his kids. Discipline is what he offers them. But there is also a sense of threat in his taut reticence. His father, who has been ‘not merely a man’s man but a bastard’s bastard’, has been a vicious bully and Jim, in his own words, ‘was a spoiled, wild kid, untouchable because of the old man’s power. I could do anything I wanted in that town, and don’t think I didn’t try.’ Jim is possessed with a need to ‘make amends’. This may account in part for his insistence on taking Georgie to Broome: Lu Fox has cleared out in that direction, and Lu’s family is part of the past requiring Jim’s amendment.

As for strange, solitary poacher Lu, who swims up into Georgie’s disaffected consciousness, he has had a father die of asbestos poisoning, a mother skewered by a tree branch in a storm, and the rest of his family – brother, sister, and adored niece and nephew – violently killed. ‘The world is holy? Maybe so. But it has teeth too,’ he has discovered. He can still recall the ‘blessed’ quality of his life with his brother’s family, its terrible erasure and his subsequent resolve to: ‘Live in secret. Be a secret.’ His brief passionate encounters with Georgie shake up the badly mixed ingredients of these three lives and he heads north, hiding himself from the seekers he wants to find him.

These three interlocking lives are gradually revealed with extraordinary richness. The parallels are worked for contrast as well as for comparison. Winton is too subtle an author to spell out what we should be able to pick up for ourselves from the clues he gives us. Unless, that is, he wants to spell it out for a reason, as when Georgie tells Jim that he and Lu ‘have a lot in common […] People view you through some weird lens of luck. Very differently of course. And you live … well in the wake of some kind of disaster.’ But her drawing this comparison only unleashes Jim’s rage when he makes her see how wrong she has been. The parallels, telling as they are, insinuate themselves into the narrative less explicitly than this; the more explicit, as in Georgie’s comment, the less crucial.

The overall motif of people making amends for what they have done with their lives and what life has done to them, the possibility of their changing, runs a poignant course through this mesmerising account of three people whose past is catching up with them in unexpected ways. It is not at all solemn or portentous, and anyone who has read, say, Cloudstreet will know how deft a stylist Winton is. His tendency to the elliptic demands the reader’s closest attention; try to skim and you’ll miss something vital – like the meaning of the title. You may also miss moments of sly wit (such as the twelve-foot shark ‘ugly as an in-law’, or Georgie’s video-viewing which ‘drew the line at Meg Ryan’), or of the natural world doing its stuff with not uncharacteristic ferocity, along with equally startling moments of piercing emotional veracity. It is a wildly personal story, but it also seems like a drama that needs to be played out against and over a terrain as rigorous and baleful as Winton’s West.

Comments powered by CComment