- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Feistian Pair

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sydney, as everybody knows, is Australia’s world city, always has been. It offers the urban metonym – Opera House sails – which, together with Uluru, is Australia to the outside world. And it generates, or generated, a particular kind of intellectual, the Sydney larrikin, rogue male. These books claim to cover two such, Bobs Hughes and Ellis. How might we receive them?

- Book 1 Title: Hughes

- Book 1 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $19.95 pb, 180 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

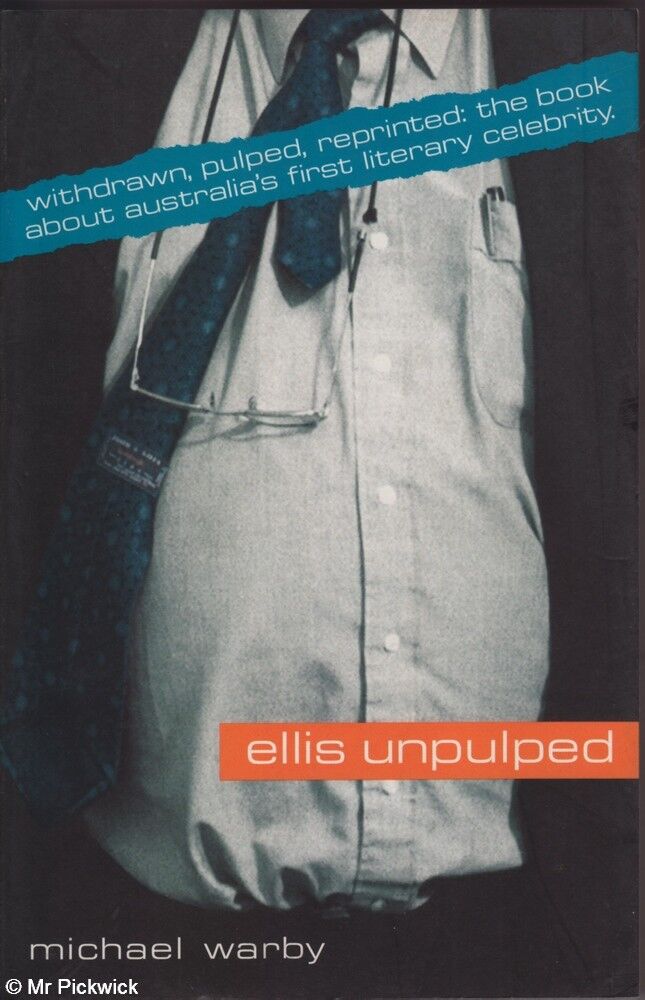

- Book 2 Title: Ellis Unpulped

- Book 2 Subtitle: Bob Ellis and the art of celebrity

- Book 2 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $19.95 pb, 209 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Riemer’s Hughes is ruminative. The text opens with an ink drawing by Hughes of the devil, and the essay is partly concerned with Hughes’s devils. The biographical substrate which most attracts Riemer is the Jesuit education to which Hughes was subjected, and which also encultured him. Riemer and Hughes were mates of a sort at the University of Sydney, refugees from vastly differing worlds, one fleeing by choice, the other transported by world-history. Riemer is a serious intellectual, of substantial culture; he reads the resonances of the underworld from Hughes’s education to Heaven and Hell in Western Art and The Fatal Shore, and puzzles over Hughes’s inability to find heaven in Sydney or Manhattan.

Hughes is nothing if not confident, especially in his prose style, perhaps most evident in The Shock of the New and American Visions, and on the screen rather than the page. This prodigious talent is anticipated in The Art of Australia. You can see it in Hughes’s sentence structure and cadences – at its best, punchy and direct. I find this approach attractive, especially in American Visions, where the direct voice is also open to contestation. Hughes rarely uses words like ‘perhaps’; Riemer, by comparison, does, partly because his essay is contemplative; Riemer is at his best, to my mind, when he is not mediating but talking to the camera direct.

Riemer traces Hughes’s stoush with the Antipodeans which, in retrospect, seems less than obvious; after all, one of Hughes’s favourites in American Visions turns out to be Edward Hopper. Hughes fled Australian suburbia, along with other expatriates, only, in his case, with an American terminus; this makes him the most modern among them. However, as Riemer understands, Hughes was bound to be disappointed; American modernism was already in decline when he arrived. Hughes’s fate is to remain ambivalent about Australia and America alike. He was to become the proverbial insider-outsider whose capacity to discern the contours of American history and culture eventually left him less equipped to make sense of Australia, as in Beyond the Fatal Shore.

Was Hughes bound to turn sour? I don’t think so. Riemer discusses and agrees with Ian Britain’s anticipation of Hughes’s decline in Once an Australian. Britain’s essay was brilliant. But its sense of decline into nostalgia largely preempts American Visions, which I take to be his greatest achievement. American Visions is brilliant precisely as cultural sociology, where American art works as a way to read American society, culture, dreams and disappointments. This is partly because Hughes tropes the United States through puritanism and hedonism, through the romantic to the industrial and postmodern sublime. American Visions covers symbols but also things; it is also a story of modernity, modernism and technology, visual design, all of which is anticipated in The Shock of the New, with its opening image of French automotive modernity. In American Visions, the curiosity about technology holds the story together from Shaker furniture, to Jefferson’s gadgetry, to the Cord and Cadillac and B52. Art and technology, like culture and power, combine.

The turning point here is The Culture of Complaint, a work aligned even in its title with the kind of cultural criticism done best in America by Christopher Lasch. For Hughes has always been a Tory radical, one for whom the fixed positions of Left and Right, utopian critique or celebrative affirmation would never do. Riemer frames the difference of this position within the difficulty of its reception. This is powerfully insightful, especially when Riemer links The Fatal Shore and Jill Ker Conway’s The Road from Coorain. Both were books bound to attract outside readers more than locals, for they could too easily be construed by insiders as shitting in the nest. The critical resonances of The Fatal Shore were with Foucault’s Discipline and Punish and Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago as much as with Australian convict historiography. It was bound to be a hit, here and overseas. Riemer’s sense is that it was also fateful for Hughes, as it clarified the extent to which Australia could sustain neither art nor the divine. The European path was one where art emerged from the sacred. In the antipodes, our origins were worse than profane. America had both myths of foundation and of mission. In the antipodes we had neither; we were just here. Hughes was drawn to America, as many of us are, by modernity and modernism, innovation and movement, but these are also destructive forces. The later point of intersection, into the 1990s, became apparent in the American fantasy that Australia might be its last frontier.

Then Hughes crashed, and snapped. As Riemer reminds, the Australian response to all this was as dismaying as the unhappy events themselves. It was as though Hughes, for some, deserved it, just as some have claimed that America deserved it. Bob Ellis’s story is different. He has always been looking for trouble, and celebrity. Michael Warby tracks this path by genre: cinema, elections, journalism, musicals, the works. Where Hughes’s church began with the Jesuits and ended up in a fascination with the grotesque, Ellis ran from Adventism to the Labor Party, with apocalypse as the binding theme. Ellis follows the path of literary revolt not against modernity but against capitalism and its stooges, all those idiots outside the ALP. Warby is right to decry this kind of Labor tribalism; one of its numerous downsides is that it fuels positions like Warby’s, who seems to imagine that narcissistic Labor tribalists are the only ones among us concerned about economic rationalism or the politics of globalisation.

Ellis emerges from all this as larger than life; what else could you say about a man who, in 1973, put in no less than seven entries for the new Australian national anthem? I can’t help but wonder, all the same, who will read this book apart from the tribalists or others who chase Labor’s pulp faction. It is, for example, as charming to be reminded of the image of Nation Review – the ferret – as it is disarming to remember its endless feuding among drunken egos who should have kept their therapy private. On a more positive note, I guess, I laughed out loud twice, though there are easier ways to get your kicks than wading through endless stories concerning contrived eccentricity. The story of Abbott and Costello, at least, has yet to resurface as a series.

If Ellis emerges from these pages as Laborist illywhacker, Warby at least has sufficient judgment to wonder what this says about Australian political culture. He’s right, I think, that Labor has too readily been viewed by intellectuals as the home of culture and virtue in Australia. This is one reason why so many sat on their hands as the Hawke-Keating government opened the process of creative destruction that Howard merely took over. Bad Leftism, in turn, draws out right-wing cant; so that Warby seems too smug in the way in which, arguing against the silly positions of opponents, he can claim easy victory for his own positions.

Hughes famously quoted a local painter in 1966 to the effect that you can’t grow up in Australia until you leave the place. Montesquieu put this with less animus when he wrote, more simply, that travel expands the mind. These days, when intellectuals seek celebrity for dubious claims that they are homeless, the question of where to be is less obvious. If politics and culture disappoint, in Paris and Manhattan as well as in Wellington and Melbourne, this is nevertheless where we are, where we have to work from. There are worse places to be than the antipodes, for we get to be insiders and outsiders without asking. Life happens, we make it, in the interval.

Comments powered by CComment