- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Floating UN

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

We read that 100,000 displaced persons will arrive in Australia in the next eighteen months. Is there no way that the people of Australia can have some control over these sweeping invitations to displaced persons. Surely there is no room in Australia for hordes of foreigners …’ reads a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald. Does it sound familiar? However, the date is 18 November 1948, a time when aggrieved readers were bombarding the papers, protesting against the influx of postwar refugees.

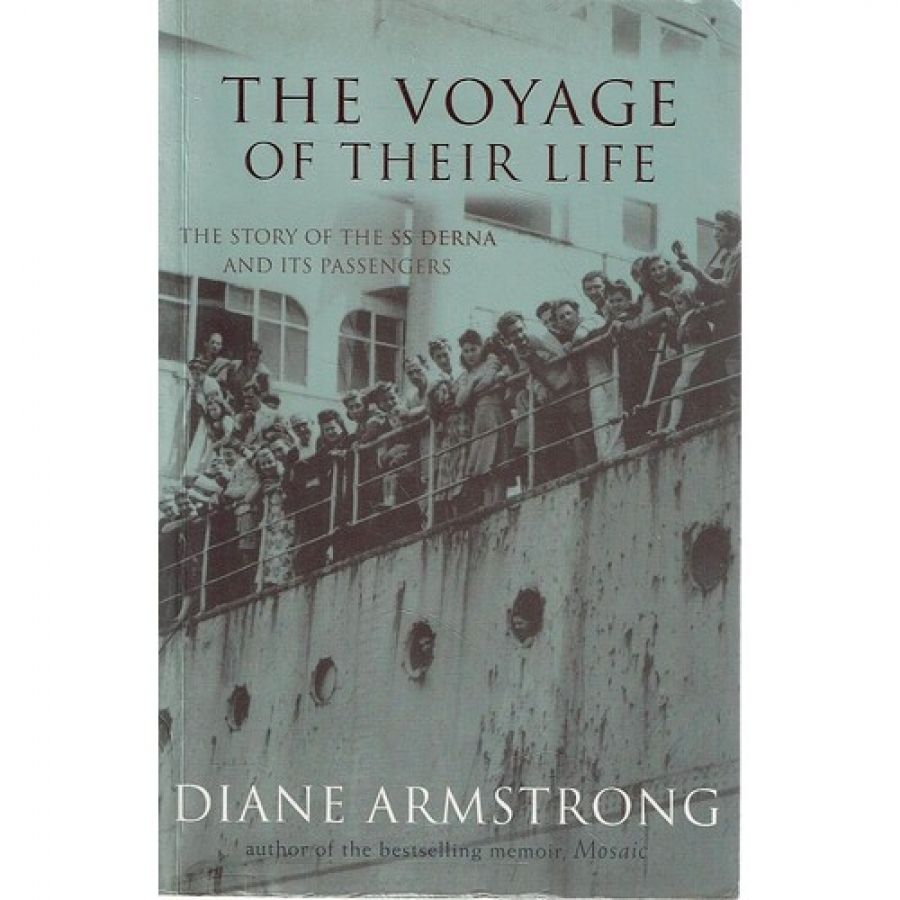

- Book 1 Title: The Voyage of Their Life

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Story of the SS Derna and Its Passengers

- Book 1 Biblio: Flamingo, $54.95hb, 483 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In preparation for the voyage, the elderly Derna was treated to an unconvincing facelift. The fresh coat of paint did nothing to remedy the structural and plumbing problems; there were no laundry facilities of any kind. The captain had grave doubts about the vessel’s seaworthiness. The crew appeared to be as difficult to keep together as the ship – a mix of Italian and Greek sailors whose relationship to one another could be gauged on a continuum ranging from resentment to loathing.

Into this rickety world came what amounted to ‘a floating United Nations’: Latvians, Estonians, Russians, Germans, French, Poles, Hungarians, Czechoslovakians, Greeks, Roma-nians. They came from concentration camps in Czechoslovakia, death camps in Poland, gulags in Siberia, forced labour camps in Latvia, and displaced persons camps in Germany and Austria. There were those for whom the Communists were saviours and those for whom they had been oppressors; those whom the Nazis had brutally tried to extinguish and those who had welcomed the Nazi forces. There were couples, singles, families with children ranging from infants to teenagers and a group of sixty-one Jewish orphans. As one of Armstrong’s subjects exclaims, on hearing about Armstrong’s project: ‘But how are you going to put all those stories together? That’s what I’d like to know!’

It is indeed a mammoth challenge that Armstrong has tackled. She has tracked down and interviewed many Derna passengers (an index of them runs to approximately 150 names). Not all of these people are treated in depth, but the book, in its early stages, might be a little taxing for the reader whose ability to file, cross-reference and relate to so many new names may not be up to the occasion. This difficulty fades as the book progresses and characters become familiar and absorbing. The second half of the book, in which the passengers look back on their post-Derna life from a perspective of fifty years, offers a satisfying overview that is almost novelistic in scope.

This section of the book can be, at times, almost unbearably moving. We meet Yvonne, a girl who was pushed into a gas chamber and then pushed out again because the normally efficient machinery of the death factory had, for once, broken down. Now she is a mature woman ‘whose spirit makes a profound impression, someone who speaks without self-pity and has rebuilt her life without bitterness’. Kitty, who was orphaned at thirteen in the Holocaust, comments: ‘Life is give and take, but I never expected it would give me so much after taking so much away.’ David, another Holocaust orphan, says: ‘When I look around the table at my family and I think how I came out here alone in 1948 with nothing, there’s a beautiful glow in my heart.’

Many of the stories echo this theme, although some survivors have not been able to find contentment. Armstrong notices that a number of children from the Derna have suffered from depression, drugs, eating disorders and alcoholism.

Armstrong gives everyone a hearing. It is ‘confronting’ for her to hear the Estonians and Latvians express their wish that the Germans had won, which of course would have meant her extinction, and yet she is able to see that, with their dread of Russian occupation, this alliance offered the only solution. Occasionally, however, this interviewer-neutrality is difficult to maintain, such as when Harold, an Estonian who served with the Wehrmacht, repeats the fabrication that the Jewish orphans faked their concentration camp tattoos for sympathy. An emotional Armstrong, who has just come from an interview with Fred, an orphan who had medical experiments performed on his unanaesthetised body at Auschwitz, realises sadly that ‘no matter what I say, I will not convince him. We hold onto the beliefs that support our perception of the world and our place in it, and facts are powerless against prejudice.’

That may indeed be true, but the facts and the lives laid out in this book shine so powerfully that they provide not just a documentation of the horrors to which mankind can descend, but a moving vision of the grace and resilience of the human spirit and its capacity to survive such atrocities.

Comments powered by CComment