- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Isle of Gore

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I felts as if I had fallen into hell,’ reflects the Keeper of the President’s Clarinet of his visit to the city of Baha. The statement is almost redundant. The sun cannot penetrate the toxic pollution of this city; he has just passed a group of children betting on the imminent death of a fly-infested man; and he is there to kidnap an hermaphrodite child-prostitute. However, his words could be voiced by most inhabitants of the fictional land of Abaza; this novel is filled with such baroque, nightmare imagery.

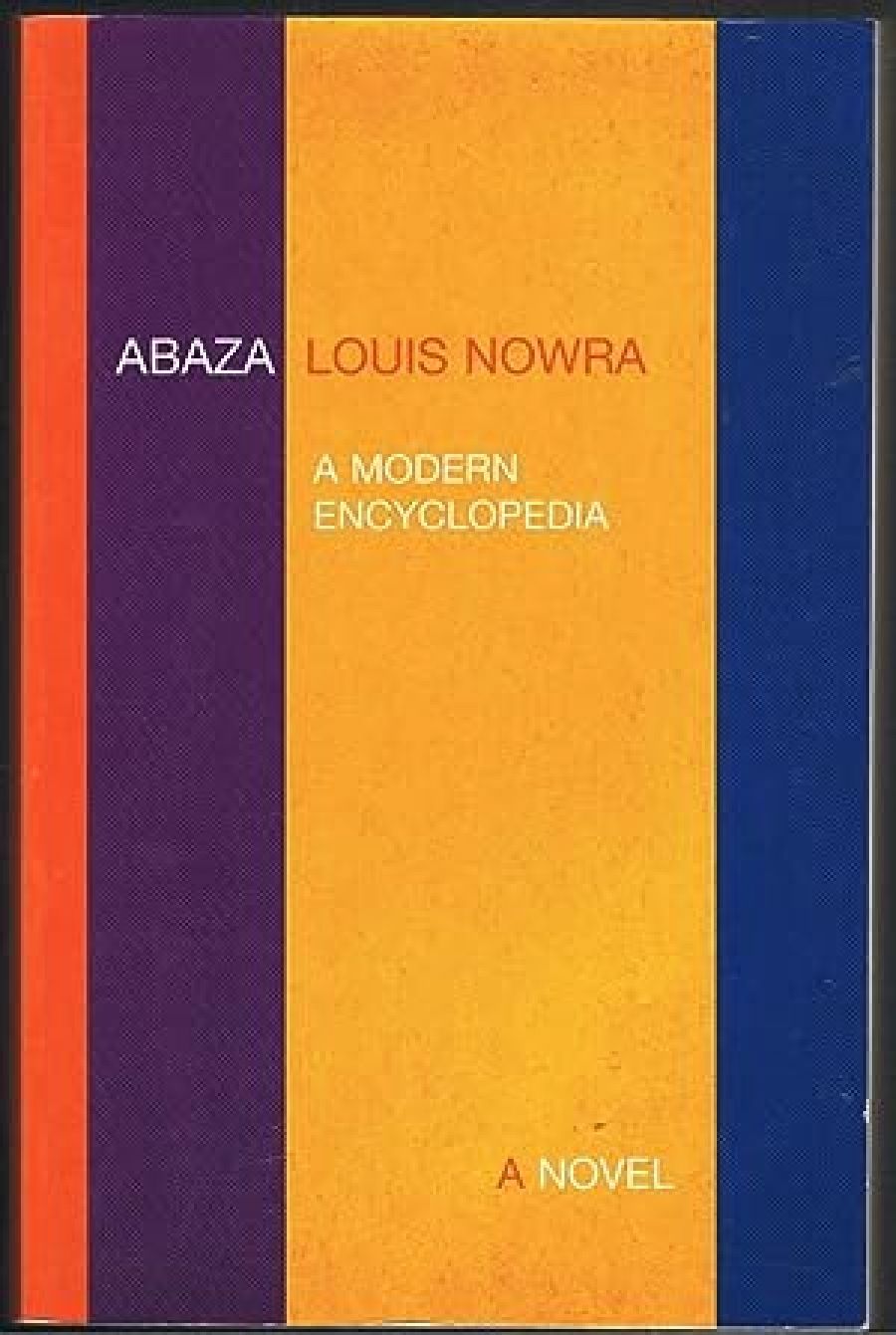

- Book 1 Title: Abaza

- Book 1 Subtitle: A modern encylopedia

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $21 pb, 475 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The subject of Nowra’s ‘encyclopedia’ is a small, war-torn Pacific Island nation. The monarchy has been overthrown by the military chief of staff, Nadu. Halfway through his presidency he reappears after a holiday looking mysteriously younger, and becomes known as the Eternal President. His murderous paranoia culminates in the interlude of ‘The Dreadful Hour’, his early-morning sessions of listing for execution people whom he imagines to be enemies, or simply doesn’t like. Nadu is eventually overthrown by the decadent President Sangana, whose obsession with jazz causes the exclamations of clarinettist Pee Wee Russell to become part of the national vocabulary. Sangana is in turn threatened by General Dugi, commander of a mob of drug-crazed children who rampage through the country carrying out obscene acts of violence. Key players in the history of the country include the tiny, hideous Aba – wit, cynic and political machinator – and Joni Velo, who rises from being Sangana’s water-server to his clarinet-keeper, and who becomes Aba’s toyboy.

A framing ‘Editor’s Introduction’ is written by Theo Porter, Visiting Professor of Pacific History at the Cairns campus of James Cook University, who explains that the encyclopedia was compiled from a manuscript of assorted pieces of paper discovered in an Abazian bookstore. Porter took over the editorship of the encyclopedia after the bloody death of his colleague, Golee Umaba, an exiled Abazian poet. Porter explains that the entries in the encyclopedia were written by participants in the historical events and gives a short biography of each contributor. He also complains about the ‘slapdash’ nature of the work of his colleague – ‘not a trained historian’ – noting that he, Porter, was forced to correct inaccuracies and to add explanatory details.

Thus the introduction makes clear that this is a ‘modern’ encyclopedia: it foregrounds the formation and ownership of historical narratives. Not only is Abaza’s history one of war, but also the telling of this history becomes an object of dispute. The introduction notes that:

Until the twentieth century encyclopedias were predicated on the idea of an underlying system of knowledge ... But as we know now the control and dissemination of knowledge is a highly political act and ... tensions between inclusiveness and selectivity, order and disorder have often troubled encyclopedists.

Late in the novel, a character complains about intellectuals who ‘want to own the past’. The sometimes conflicting points of view of different contributors to this encyclopedia indeed underline the subjective nature of historical narratives. This polyphonic storytelling, more closely than a single, universalising narratorial voice, reflects the way an historical event engenders varying experiences.

An unusual reading experience arises from the encyclopedic form. The cross-references to different entries invite you to read in a choose-your-own-adventure fashion, but the appearance and eventual solution of several narrative mysteries suggest that a cover-to-cover reading is fruitful. The story emerges in a fragmentary fashion, like the composition of a jigsaw, a process that generates its own intrigue. However, the fact of the story forming from all directions does mean that narrative momentum arises relatively late in the book. Also, the different voices of each entry can be a little disorienting because their authorship is not stated until the end of each section. At first you read this fiction as you might a textbook: because you need more information, rather than because you’re interested in a plotline.

Nowra has fun with his writing, punning with names such as Homme on the Range (a resort for gay men) and giving latitude and longitude coordinates for Abaza, which in fact locate it almost on top of Cairns (perhaps suggesting, mischievously, that it exists only in the minds of the warring editors there?). There is some nice, po-faced silliness — an entry for ‘Aahu’ notes that it is ‘an intense pain resulting from having one’s skin punctured by a poisonous fish’ — and the lecturing, textbook style of some entries is comically interrupted by profane bursts of frustration from their authors. Well-placed potshots are taken at various elements of contemporary culture: ‘Koi’, for example, is a youth movement emphasising ‘stylish clothes, solo dancing, and a nonchalant attitude’, whose apex of success is dance-floor applause for some ‘new subtle and special foot movement’. However, these humorous notes are overwhelmed by the darkness of the book as a whole. Tegi, the Dream Kid is a violent cartoon revered by much of the Abazian population; in many ways, the novel mirrors it.

While the characters are colourful, their lack of emotional depth means that, like cartoon characters, they remain flat and distanced. Their rare expressions of more subtle feelings are dulled by the brittle, comic tone that dominates the novel. Further, they are all unpleasant – lecherous, violent or selfish to varying degrees – and they are all objects of satire. Because there are no sympathetic characters, it’s hard to care what happens to any of them.

But what is most striking about this fiction is its relentless violence. The attacks carried out by Dugi’s warriors almost become ridiculous in the ever-increasing inventiveness of their orgiastic violence. The matter-of-fact presentation of the violence exacerbates the cartoonish sense of its emotional inconsequentiality. Professor Eba, whose entries ‘have obviously been written with a pencil held between his toes’, sums up his plight after an attack by a machete-wielding child: ‘All my research was gone, my life as an academic was over and I had lost my arms.’ The constancy and extremity of this violence might be justified if it had a point, but it becomes pornographic in its gratuitousness. Its perpetrators escape and its victims suffer randomly. Perhaps the author meant to convey the indiscriminate nature of oppression, or to draw attention to our desensitisation to such acts. But with no endpoint to his horror, Nowra merely appears to revel in this subject matter.

In fact, the worldview conveyed by this novel is primarily nihilistic. Characters often voice such cynical aphorisms as ‘creation and destruction [are] the same impulse’, and ‘life is anything but good ... humans will always hurt other humans’. Of course, an encyclopedia is not supposed to convey a thesis but, rather, to organise information. Nowra certainly displays a model-maker’s pleasure, and skill, in constructing a microcosm. Yet this is actually a work of fiction, not a reference book, and we are entitled to wonder about its intent. Although Umaba claims that ‘history is defined by Love Won and Love Lost’, the novel validates Aba’s view that ‘History is merely the conflation of rumour, gossip, who copulated with whom, and who got a bullet in the head’.

Comments powered by CComment