- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Readers of Kayang and Me should not be lulled by the beauty of its prose or by its seemingly easy location within the now-familiar genre of indigenous life story. This book dislodges its white readers from positions of quietude or certainty, and takes us into a world marked by irredeemable loss – our own as well as Noongars’. Among other things, Kayang and Me points to the crucial things that settler-colonisers have lost or forsaken in the mistaken pursuit of the bounties of colonisation, and it calls for nothing less than a radical remaking of the Australian nation-state. Significantly, it installs writing and reading as practices through which the past, present and future might come to be differently known and newly imagined. The white reader is shown to be implicated in the story she holds in her hands, in its vision of another future as well as in its tragic present and past.

- Book 1 Title: Kayang and Me

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP, $29.95 pb, 270 pp

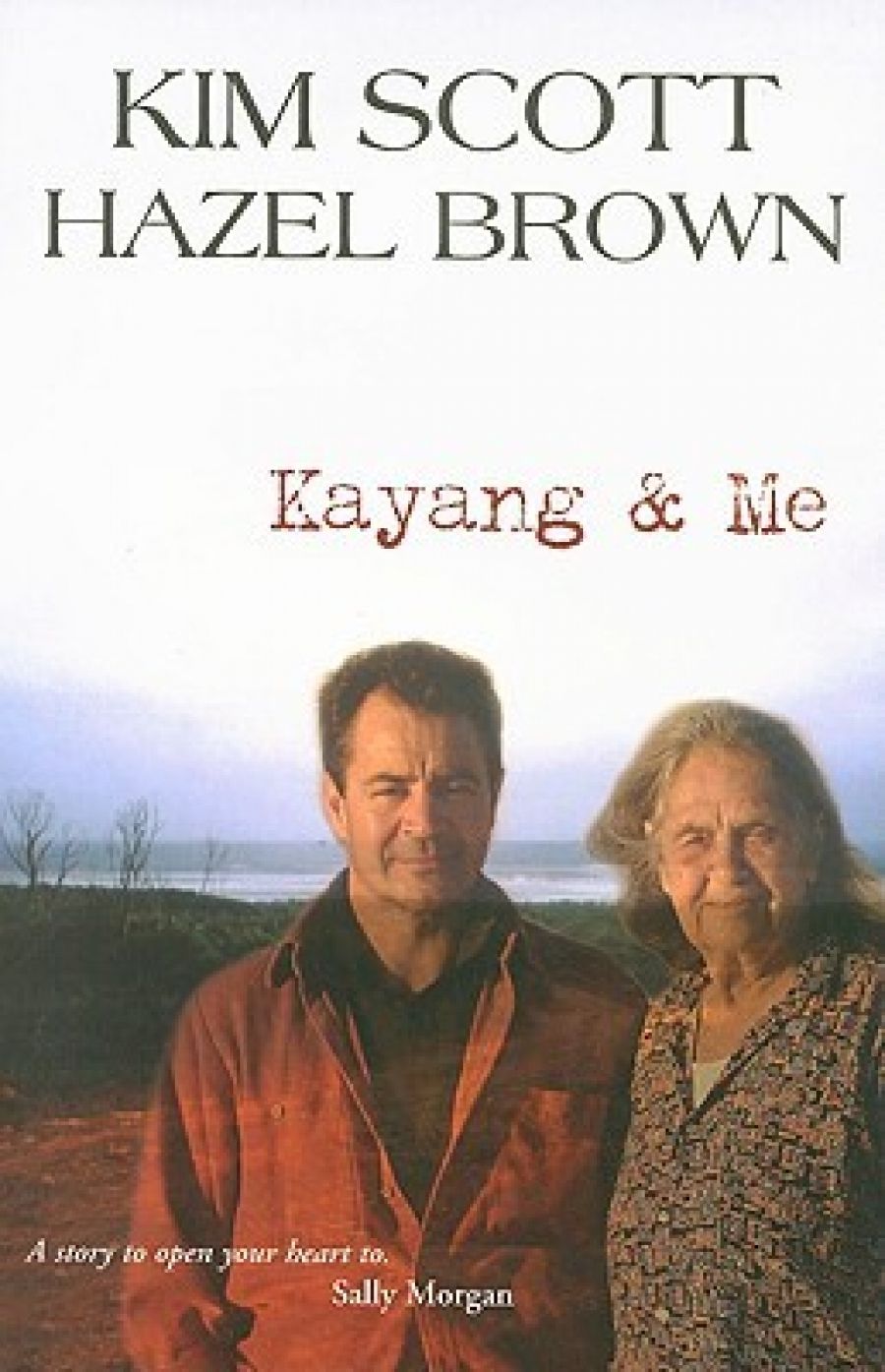

Kayang and Me tells the history of the colonisation of the south coast regions of Western Australia, in particular around the small town of Ravensthorpe, fifty kilometres inland, and the old port of Hopetoun. This history is recounted within the folds of another story – the encounter between Miles Franklin Award-winning novelist Kim Scott and Hazel Brown, a Noongar senior elder whom Scott calls Kayang, translated variously as ‘aunty’, ‘grandmother’ and ‘elder’. The book maps Scott and Brown’s coming to know each other across a distance produced by the violences of colonisation that have torn Noongar communities apart, forcing some people into towns and wadjela (white) lives, isolated from other Noongars, while others live as Noongars. Throughout the telling of the troubled story of colonisation, questions are raised about one’s place: who can call himself Noongar? Who goes by the name wadjela, and who by wadjela Noongar? Scott’s own life has followed a path across this troubled history as he found his way back to the Noongar family from which he is descended. Kayang and Me is then a book of return and of new possibilities, as well as a book of loss.

When Scott looks for the things that will bind him to Brown and her extended family, and that will thereby give him a place among these Noongars who have been so invaded and dispersed, he first turns to genealogy, ‘white man’s stuff’, as Brown puts it. With pen and paper beside me, I followed Scott in his search through the labyrinth of family, drawing lines of connection as they began to emerge in the story, trying to keep track of the lines that will ensure a place for him. In telling his initial quest in this way, in inviting a reader to make diagrams of lines of descent, Scott can reproduce in his reader some of the tensions of his quest. He sets the reader off in pursuit of a goal that at first seems necessary and impelling, but that turns out to be beside the point. Scott’s bond to this Noongar family turns out not to be fixed or describable by genealogical diagrams.

Although the lines intersect, describing familial relationships between Brown and Scott, the truth of their bond lies elsewhere: in an orientation towards other Noongars and to country, in a shared past and future. Brown shows Scott this through the traditional stories she tells him of the land and its spirits, through the history of the places she knows, by indicating where the land carries the indelible marks of earlier presences. Scott comes to know that ‘an old spirit rests in the land’ and that ‘its people are the catalyst of its reawakening’. This spirit’s awakening is an exciting possibility for Scott. Significantly, he does not speak of the spirit as if it belonged in a sweet story that can be listened to with easy pleasure by non-indigenous Australians: this spirit cannot be relegated to the realm of myth. It is a force, and its arousal from sleep will involve strategic, political interventions.

These might include, in the first instance, ‘a moratorium, a time of exclusion’ during which Noongar and white societies live apart, enabling the consolidation of Noongar heritages. Scott and Brown are not meaning, however, a ‘nostalgic retreat into land or to some simple pre-colonial past’. The heritage of which they speak includes the powers of innovation and adaptation, cooperation and creativity, and of the kind of knowledge that comes from long and deep relationship to place. They do mean, though, an expansion of the Noongar world ‘so that there is one world, not two’, and therefore a revisioning of the Australian nation-state as ‘grafted onto Indigenous roots’. After such a consolidation and then expansion of the Noongar world, ‘exchange and interaction from relatively equal positions should be possible’, they suggest.

While Kayang and Me describes hope and regeneration, it shows also that some losses are irrecoverable. Kayang and Me describes the massacre, around 1880, of more than thirty people at Cocanarup, four miles from Ravensthorpe. This massacre was a reprisal for the death by spearing of a white settler, John Dunn, who had raped a thirteen-year-old girl. This killing was on such a scale that the area between Gnowangerup and Esperance has become like a ghost country. So many people were killed, and so many of those not killed fled from the area, that few Noongars now remain. There is talk of a mass grave where the bodies of the slain men, women and children were buried by the settlers; when family members return to the site of the massacre they find ‘bits and pieces’: bones, remnants of cloth, some brass buttons. There is evidence of bodies disinterred by wild dogs.

These are stories of horror, reminiscent of those accounts of eerie towns and rural areas in Poland whose entire populations of Jews were removed, and mostly murdered, during World War II, and where all that remains of them is a ghostly presence. While the relevance of the term genocide to describe the Australian scene of colonisation is being contested among white commentators, there are clear associations between the impulses underlying these two obscenities. Kayang and Me uncovers some of these impulses, as they are found for instance in the explicit intentions of A.O. Neville to ‘breed out’ Aboriginality, or in the practices of doctors in the south coast area in the late 1950s who refused to treat Noongar babies. As Brown says: ‘You’d think … they wanted to get rid of all the Aboriginal people. Genocide in Gnowangerup. Go down there to Gnowangerup cemetery, and there’s a row of little graves.’ These and their contemporary versions are crimes that have produced incalculable loss, and yet some white Australians persist in trying to calculate the loss, numbering the dead, deciding whether or not these numbers add up to war, to genocide. Against this, Kayang and Me shows that indigenous loss is unknowable, unspeakable, but that efforts must be made to imagine it. This is the kind of necessary impossibility that clever writing such as Kayang and Me approaches in its efforts newly to envisage this country’s past, present and future.

Comments powered by CComment