- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The hybrid state

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

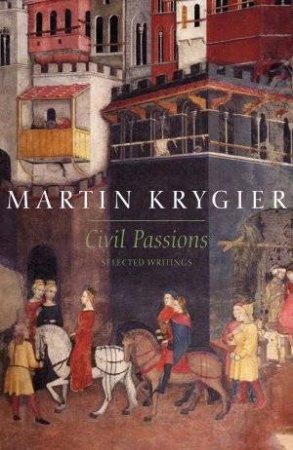

Martin Krygier’s deft, discursive prose could persuade anyone except an ironclad ideologue that it is exhilarating as well as healthy to examine one’s prejudices and complacencies. Krygier is also a writer possessed of a frank openness that gives credence to the idea that you can judge a book by its cover. I suspect he’d also enjoy the piquancy of maxim busting. The cover of Civil Passions is a particularly beautiful one: a detail of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s 1338–40 fresco, the Allegory of Good Government. Its Giottoesque precision and its colour – those luminous Sienese pinks and reds – would be reason enough to use it. But there is a deeper fitness to the choice, and it has to do with what Krygier describes as his destined mode of being: one of hybridity.

- Book 1 Title: Civil Passions

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected Writings

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $34.95 pb, 303 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Martin Krygier is a professor of law with a generalist’s enthusiasms. Born in Australia, he is the child of Polish Jews. His interests range across – and beyond – politics, law, psychology, history and philosophy. He is as at home analysing the strained dichotomies of Australia’s ‘history wars’ as he is examining Polish post-communism. None of the essays in Civil Passions has any obvious truck with late medieval Christian art, and Siena doesn’t rate a mention; but the annexing of one perfected art to Krygier’s pursuit of its equivalent in another sphere and time seems perfectly natural and apposite. It suggests a European presumption that Western art is part of his bailiwick, a presumption that sits comfortably with the unforced conviction that his is an Australian bailiwick. This man, by his own say-so, can watch cricket for days, and days, without being bored. If he can also muse at length about the nature and provenance of Hungarian pessimism, then that’s a bonus of the hybrid state. A bonus for all of us.

He remarks early in the book that hybrids, like himself, have a vantage point, simultaneously inside and outside the culture in which they were raised. Robert Dessaix has often made a related point about the paradoxical advantage of being antipodean: in our geographical remoteness, we Australians feel obliged to know not just ourselves but the rest of the world – even if they don’t know us.

It is a surreal experience to read these essays, or indeed Dessaix, at this time, when the rhetorical frames of national and international politics are becoming more and more reductive, squeezing us into smaller and smaller spaces. It seems even more absurd to be reading such expansive exercises, written by such an intellectually Rabelaisian Australian, at a time when our pygmy pundits seem to think they can define our national being, even if only negatively – by pillorying what is ‘unAustralian’. But that’s dead-end thinking, and it is one of the signal virtues of Civil Passions that it doesn’t indulge in dead ends. That does not mean that Krygier goes in for utopias, either: he is bracingly realist, and disarmingly honest.

There is much to be realist and honest about. The essays in this collection are an index of the author’s occupations and preoccupations over twenty years. They are all written for a general public – written not down but out, as Krygier puts it, acknowledging his debt to George Orwell. Principally, they advance his complex and persuasive case for a civil society. From the outset, he outlines what he means by a civil society by alluding to the heroic endeavours of Adam Michnik, Polish writer, historian, newspaper editor and adviser to Solidarity. Michnik is a prophetic figure for Krygier and for his case, embodied proof that civil society need not be bland society. Krygier writes:

… civility does not require some anaemic politeness, where everyone avoids saying what they mean. Civil debate can be, and often needs to be, heated, impassioned, angry. It can be bruising. But short of war, a serious business not lightly to be embarked upon, a society is blessed when passions are contained within civil limits. And it makes sense to be passionate about that very containment.

The figure of Michnik as Krygier presents him is a huge one, ‘a force of nature, huge in passions and appetites, withering in his opinions, acerbic, brilliant’. It is evident that ‘containment’, for such a man, was no small matter. And in communist Poland, with no political or social context to support him, ‘containing’ passion in order to initiate structures that would serve the general good, was a noble choice. Krygier: ‘That choice is as noble as it is rare. But it can also get you killed. And it pays to be brave. We are not all brave, and a society in which we have to be brave to be civil is a hard one to survive.’

His preference, and the burden of much of the book, is for the creation of the kind of civil society conceived as a floor, a foundation for peoples’ lives, not the high ceiling of their aspiration. He invokes Ernest Gellner, from his book Conditions of Liberty: Civil Society and Its Rivals (1994):

The price of liberty may once have been eternal vigilance: the splendid thing about Civil Society is that even the absent-minded, or those preoccupied with their private concerns or for any other reason ill-suited to the exercise of eternal and intimidating vigilance, can look forward to enjoying their liberty.

Even in the essays not specifically concerned with civil society, there is a thread running through that argues for the conditions that would enable it to thrive. Krygier is eloquent and incisive about language, about rhetoric (an adept himself, he understands its use, and abuse). He is also extremely interesting on the subject of that much-abused notion, the rule of law. Here, his professional legal experience and scholarship help make his case for a rule of law that, as he puts it, focuses on ends rather than means; a rule of law that ‘counts’ with people, that is clear, not contradictory, and able to be known and understood by those to whom it applies. The rule of law, he claims, is not the good society. It’s a minimal condition. But it’s not the only game in town.

Imagine this: instead of our prevailing political static about law and order, terrorism and Telstra, we have an ongoing (and televised) Senate hearing in which Martin Krygier is debating Geoffrey Robertson about the rule of law. The bells don’t have to be rung to elicit a quorum and – an even wilder fantasy – the civility, the decorum of the debate, and some ounces of its intellectual weight, in time migrate across to the other place and parliament becomes again what it might be.

Communism fell. So many things are possible.

Part of the pleasure – and edification – of Civil Passions lies in the way it combines advocacy for a civil society with a personal history in which conviction, nimbleness, loyalty and wry self-deprecation all play a part. Martin Krygier is the son of Richard Krygier, founder and publisher of Quadrant magazine. Like his father, he has been a passionate anti-communist. A decade ago, such a history and lineage would have given many people, myself included, the impression that they could confidently map his mind, anticipate his reactions – dismiss him ‘by category’, as he puts it. It’s too easy to say that was a mistake. But it is not difficult to take heart from the way Krygier implicates himself in a related tribalism – and then steps beyond it. It’s part of the serious ‘lightness of being’ of the book that he can castigate polemical mind sets, convict himself, and then point to a resolution, a new way which includes comedy as well as tragedy in its progress. Michnik, again, is a guide here, in his refusal to divide the world into ‘angels and maggots’. And like Michnik, Krygier is psychologically subtle in his rejection of reflex polarising:

… if the substance over which we debate is more complex than commonly admitted in our public debates, so too might be the reasons people have for their views. At least one does well to start with that presumption, rather than join one or other of the packs in which Australian polemicists like to hunt.

This is not an argument for relativism or boundless liberalism: it is a prescription for understanding, leading to that elusive state, reconciliation.

There is much else here, about Poland, communism and post-communism, about gypsies, about being that unlikely amalgam, a conservative liberal socialist. There are stinging critiques (of Cassandra Pybus on James McAuley, and of Keith Windschuttle’s The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, for example). The book in itself is a chapter in Australia’s intellectual history (and as such warrants an index). The joy of it is that it is written with such a light, ironic touch, and that its zest confounds Krygier’s own pessimism.

Comments powered by CComment