- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bird's-eye view

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

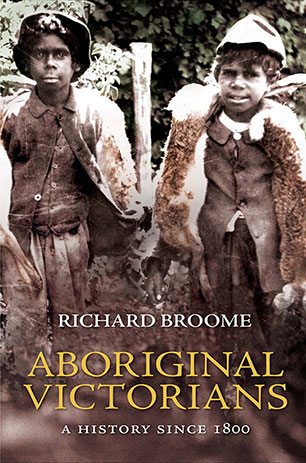

The sepia-toned photograph on the front cover of historian Richard Broome’s new book presents the reader with two young indigenous Australian boys, taken around 1900 at Ramahyuck, an ‘Aboriginal mission’. Bright-eyed, alert and pleased with themselves in white shirts, woollen vests, jackets and trousers, they appear to be wearing possum or kangaroo skin cloaks. A closer look, however, reveals that the furs draped thickly around their shoulders are not iconic cloaks, but their successful catch of tasty rabbits.

- Book 1 Title: Aboriginal Victorians

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history since 1800

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $39.95 pb, 467 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Sometimes Broome’s effort to achieve wider national coverage may cause the reader to feel that they are wading through a sea of facts. At other times, the reader gets pushed along in the exciting currents of sports heroism and other achievements. The diversity of indigenous experiences is clear: from families who managed independent lives, to those held too tightly under gaol-like mission surveillance, to families broken up and destroyed, to those who led hard-working lives, and those forced into hopelessness and mendicancy. While personal responsibility is not ignored, the reader gains a positive idea of the carefully held indigenous values of family, community, individual courage and persistence. Although at times I craved some literary lacework, Broome writes clearly and simply. His knowledge is excellent and his documentary foundations solid: the archival documents, the interviews and other sources appear in the footnotes. The sources appear so rich and diverse that obviously many more questions will be explored by future scholars in the field.

The ‘history wars’ are largely irrelevant to Broome’s purposes, though he opines matter-of-factly on genocide and willingly proffers informed estimates of population sizes and losses due to disease and violence. He is at pains to be balanced, attempting to provide readers with insights into indigenous practices of which he suspects they may disapprove. In even-handed fashion, he points out both the hard work of non-indigenous activists and the racist polemic and belief that arose repeatedly throughout the different epochs of Australian history.

Yet despite the ‘master narrative’ of general history, the ‘message’ is not altogether obvious, and nor does the story-telling seem to disguise any wider collegial conspiracies. The framework appears predictable enough – Wild Times, Transformations, Assimilationism, Renaissance – set in a chronological framework. However, this history is not just a creation of the white policymakers, the missionaries, protectors and other implementers of policy, but of the indigenous individuals, communities and families. Throughout, Broome acknowledges divisions between different indigenous families and communities, and makes refreshing attempts to curb utopian projections. While he does not shy away from land ownership and other such ‘political’ issues, the tone is always measured and its conclusions are conservative.

While well enough informed by anthropological insights, Broome leaves no spare room for cross-cultural complexities, interpretative conflicts or dilemmas. While he acknowledges that his colleague Inga Clendinnen ‘inspired me to try harder when I write’, the work appears little influenced by the ethnographical probings of Greg Dening or Clendinnen. Broome’s perspective is humanist, in the sense that he knows people are both alike and different, with diverse cultures and living agendas. He is less fascinated by the cultural exotic than he is in writing indigenous Australians onto the undulating playing field of a common humanity.

While any general history can in theory be more extensive, their value lies in prompting us to consider new ways to think about future efforts. Despite the book’s fascinating illustrations of people, evidence of material culture and landscape is not of equal interest to Broome as written sources. Nor is there much attention to international influences or borrowings. Although a reserve and a man are called ‘Jim Crow’, Broome does not explore the links of this phenomenon with events taking place in the US. While some reference is made to avoiding the mendicancy engendered by the British poor-house, the Victorian hodge-podge of state policies may have been better understood in relation to events in other Australian colonies and other settler societies in the Pacific and the northern hemisphere. Without such lenses, the underpinnings of Victorian initiatives are left looking very particular, if not downright peculiar.

Within the post-1800 frame of Broome’s intense gaze on ‘Victoria’, however, he has produced an admirable work of original research in plain English. Towards the end of Aboriginal Victorians, Broome refers to the painted ‘layerings’ of cultural practice observed on cave art. Going along with an indigenous man’s analysis from the Northern Territory, he likens these paintings to the layers of history that Victorian Aborigines can still retrieve from what is mistakenly seen as a ‘lost’ or ‘washed away’ past. In this book, via primarily text-based research, we can only follow the layerings as far back as 1800. Albeit a valuable and even extensive beginning, such a ‘history’ creates a truncated past.

Even with the benefits of oral history, the challenge of piecing together post-contact history is difficult in itself, so historians rarely attempt to add any analysis of pre-contact times. While Geoffrey Blainey’s Triumph of the Nomads (1975) was an exception, the task has generally been left to the archaeologists and prehistorians. After the ‘history wars’, historians may be too nervous to undertake the speculations imperative for prehistory work. Yet, with an increasing interest in ‘deep time’, in human–land relationships throughout climatic changes, it may indeed be time for historians to attempt to extend their histories to the times before 1788, before 1800. After all, historians have a talent for intelligibly synthesising knowledge across a range of disciplines, and for piecing the facts and theories together into memorable narratives that can shift national agendas.

In making indigenous Victorians the central characters of this new book, Broome has to an extent already changed the agenda. The reader gains strong insights into how they managed to survive their everyday, multiple-generational sufferings of poverty, ill health and racism. We also learn of their less successful struggles to carry their worse losses: the family break-ups, the lost children, the prohibited marriages, their high imprisonment rate, quashed political initiatives, and struggles over alcohol and violence. They suffered severe curbing, if not actual prohibitions, against taking up economic and educational opportunities. Amid discouragements, many energetic political campaigns have seen successful outcomes, and a language, dance and cultural revival continues, dramatised in spaces such as the Melbourne Museum’s Bunjilaka exhibition and the indigenous languages courses now taught in schools. Victorian Aboriginal people survived throughout tens of thousands of years of history, strengthened by their special connection with country and family. Today, Victorian Aborigines still celebrate their modern culture and its creativity, and value the profound continuities that extend into the multiple layerings of a deep history of land, people and time.

Comments powered by CComment