- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Remembering Vietnam

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For most Australians, certainly for those under the age of forty, ‘Vietnam’ is either an item on school curricula or a slightly off-the-beaten-path tourist destination. History or holiday. This may affront some, especially the small groups on either side of the 1960s cultural and political divide that cannot let go, but it is a sign of a generational shift and of the creation of the distance between ourselves and the event that is necessary for enhanced understanding and reconciliation between Australians and the Vietnamese.

- Book 1 Title: Australia’s Battlefields in Viet Nam

- Book 1 Subtitle: A traveller’s guide

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.95pb, 235pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

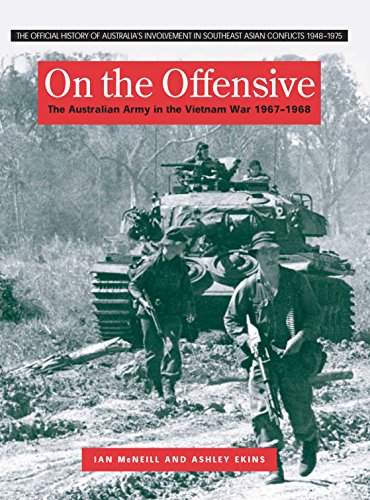

- Book 2 Title: On the Offensive

- Book 2 Subtitle: The Australian Army in the Vietnam War 1967–1968

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $80hb, 679pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Ian McNeill and Ashley Ekins’s thick and weighty tome, On the Offensive: The Australian Army in the Vietnam War 1967–1968, is another volume in the current official series dealing with Australian involvement in postwar South-East Asian conflicts under the overall direction of Peter Edwards. Substantially delayed by McNeill’s untimely death in 1998, what was to have been a single volume dealing with Australian operations on the ground from 1967 until the end of Australian involvement in 1971 has now been split into two, with a second volume (the final in the series) scheduled for publication late in 2004.

Official history is a maligned and misunderstood genre in an age that increasingly regards anything ‘official’ as automatically suspect. This volume, like the others in the series, is intended as a work of record and reference, and in this it is thoroughly successful. No official historian regards his or her work as the ‘final word’ on the subject (quite the contrary, in fact). As the great American historian Kent Roberts Greenfield observed of the massive US Army series on World War II, official histories are not intended as bedtime reading. They are neither popular works nor intended to close off discussion of a topic. Extensively documented, with excellent supporting maps and appendices, and lavishly illustrated, On the Offensive will be mined assiduously by other writers for years to come, even when, or perhaps especially when, they challenge its conclusions and assumptions.

The central concern of the volume is to show the difficulties encountered by the Australian Army in operating in Phuoc Tuy province with a force too small for the tasks allotted to it. One consequence of this was the decision to construct a barrier minefield, designed to reduce enemy access to parts of the province and to make the task force’s resources go further, but which in fact became a valuable source of ordnance for the enemy, who lifted several thousand Australian-laid mines and used them against Australian troops. The book culminates with the intense fighting brought on by the enemy’s Tet offensive in early 1968, and deals with well-known actions such as the fights for the Fire Support Bases Coral and Balmoral, and with less well-known, but no less fierce, actions such as Suoi Chau Pha. The volume does not shy away from incidents that cast an unfavourable light on its subject, such as the murder of a junior officer by one of his soldiers in December 1967, which has already earned it some small measure of controversy in the media.

DROPCAP

In recent years, increasing numbers of Vietnam-era veterans and general tourists have visited Vietnam to lay ghosts and gain a greater understanding of the war, the country and its people. Gary McKay, who served late in the Australian involvement as an infantry platoon commander and who has written of his experiences elsewhere, has produced a guide to the country for those who go seeking the Vietnam War, with a strong emphasis on sites of Australian significance.

The test of a book such as Australia’s Battlefields in Vietnam: A Traveller’s Guide is its utility to the battlefield tourist, whose needs vary. I haven’t ‘field tested’ this volume, so must judge it against the many works of its kind that have accompanied me across battlefields in Britain, western Europe, Turkey, South Korea and North America over the years.

The book divides the country into regions, provides some potted history of areas and activities, explains the significance of a site and then gives some detail about that site today: how to get there, what to look for, the extent to which the area has changed since the war (in some cases, clearly, development has been dramatic, a problem that the battlefield student frequently encounters on the old Western Front in France and Belgium, and that makes reconstructing an action in one’s mind doubly difficult).

So far, so good. The volume is compact, and would fit comfortably into the pocket of a field jacket, while being robust enough to withstand regular use. The advice on the various sites, their accessibility and the continuing danger from unretrieved ordnance, is helpful; the commentary is balanced and pays due attention to memorials and cemeteries erected by the Vietnamese government (although cemeteries for the dead of the old Republic of [South] Vietnam were largely destroyed by the victors after 1975).

The major shortcoming, for the non-veteran or the less assiduous student of the war, is the almost complete lack of maps accompanying the description of actions and commentary on the sites today. Good tactical maps are essential when viewing the ground, even, or especially, when the ground has changed since the war. The visitor wanting to understand the ebb and flow of a fight, and the role played by ground in determining the action, gets little help from this guide at precisely the point where they need it most. Even the discussion of static sites such as the barrier minefield or the Australian base at Nui Dat would be infinitely improved by the provision of the sorts of maps contained in McNeill and Ekins’s book, especially for those who never served there. Even sketch maps are better than no maps.

In Australia at least, the Vietnam War is now history, its veterans ageing, the post-1975 outflow of Vietnamese refugees and migrants successfully absorbed into the mainstream population and making their own contribution to the fashioning of modern Australia. As the passions of the time have cooled, the capacity to understand complex events and their consequences increases, whether for individuals or at the national level.

Comments powered by CComment