- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bobby Burns is late

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Not since Henry Parkes has New South Wales had such a literary-minded premier as Bob Carr. Parkes published his own poems and wrote two earnest volumes of autobiography. Carr, so far, has tried his hand at a novel, a memoir and a diary, as well as writing lots of occasional pieces. Carr, like Parkes, was a journalist before becoming a professional politician. Parkes, too, dragged himself from humble beginnings to a position where he could use official letterhead to arrange meetings with those he admired. Carr has sought out writers such as Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal to autograph his copies of their books and to join him at dinner. Once established, Parkes’s main aim was to stay in power. It was his only source of income, so his manipulation of factions, policies and the electorate all focused on that end. Graham Freudenberg has said of Carr: ‘Labor politics is central to Bob’s identity … if you took the politics away from Bob there would be nothing much left.’ But unlike Carr, Parkes did not have the option of moving to federal politics (he died before 1901). After Federation, NSW politics was stripped of talent as its leaders, including Edmund Barton, William Lyne and George Reid, made the move. Reid, a long-serving and highly effective NSW premier, is one of only two state premiers ever to have succeeded in becoming prime minister, the other being Joe Lyons.

- Book 1 Title: What Australia Means to Me

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $9.95 pb, 76 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

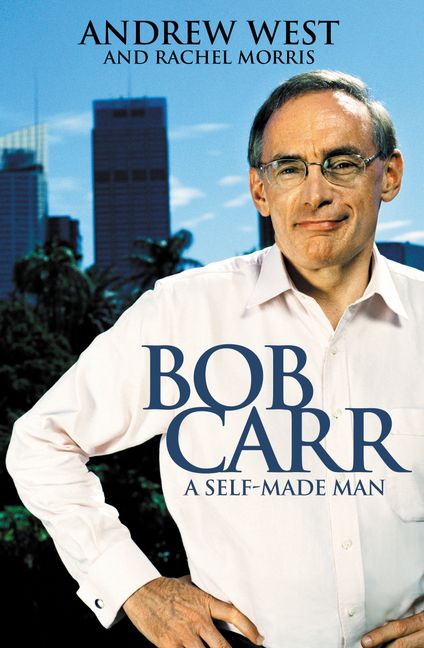

- Book 2 Title: Bob Carr

- Book 2 Subtitle: A self-made man

- Book 2 Biblio: HarperCollins, $35 pb, 431 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The authors of Bob Carr: A Self-Made Man are journalists, too, West with the Sun-Herald, Morris with the Daily Telegraph. Their book was researched and written over ten months, mostly in 2002. Carr himself gave more than twenty hours of interviews, and the authors conducted more than seventy interviews with ‘relatives, friends, former friends, colleagues, employers and enemies’. Some have undoubtedly been more frank than others. Laurie Brereton was so unforthcoming as to be useless, while Paul Keating declined to be interviewed at all. Carr’s life is clearly a work in progress.

Early chapters here are indebted to the memoir published in his Thoughtlines (2002), and later chapters are greatly enlivened by quotations from Carr’s diaries, reworked by Marilyn Dodkin for publication. Towards the end, a detailed plan of the steps needed to draft him to the leadership of the ALP is laid out, though this has received less attention than the revelation in the epilogue interview soon after his successful re-election as NSW premier last March that he still muses about Canberra.

Biographies of politicians in mid-career are an interesting gamble. The revelations contained in Blanche D’Alpuget’s biography of Bob Hawke did him no harm with the electorate, whereas Christine Wallace’s life of John Hewson turned many readers against him. Those who distrust Carr and believe him to be too opportunistic will find confirmation here. But the portrait of the working-class boy who has dragged himself up by his own determination and hard work could win sympathy.

The opening sentences capture the quintessential Carr. The nine-year old boy is pacing up and down outside his grandmother’s house in Maroubra waiting for the utility that is coming to move the Carrs into their own house. ‘Bobby Burns is late,’ he says in his clear, insistent manner. ‘He’s late.’ Impatience and anger are recurring themes throughout Carr’s life. But so are self-discipline, invoked by the image of the boy studying late into the night and schooling himself through numerous political disappointments, usually engineered by the disastrous Graeme Richardson, to keep slogging at the ultimate goal of power. When, in 1988, his arm is twisted to take over the leadership in NSW, he writes in his diary, according to West and Morris: ‘I felt a jolt in my stomach. What am I getting myself in for? It could destroy my career in four years’ time. It’s my fate.’ The Dodkin version of the diary is slightly different, however. ‘I feel a jolt in the stomach at what I’m letting myself in for. It will destroy my career in four years. Everything’s altered. It’s my fate, buffeted by a big salary, a car and a staff.’

So successfully has Carr created the image of himself as an intellectual that the facts of his childhood amid the sand hills of Matraville may come as a surprise. They show an able boy with some sensitivity and a great capacity for absorbing ideas and information growing up in a world bounded by his father’s experience as a railway engine driver, unionist and disaffected Catholic. Carr’s education was less than satisfying, but, as is pointed out several times, his belief in education is deeply personal. Although he spent four years at the University of New South Wales, it was at a time when the university was producing mainly engineers and scientists, people who were needed by the developing economy, but not destined to govern NSW. Carr’s bright contemporaries in the humanities and social sciences were, like him, absorbed mainly by the media, advertising and public relations, where they all lived on their wits.

Education is one of the policy areas that West and Morris think Carr could carry into federal politics; another is his concern for the environment. Some of his thoughts on both can be found in his little text What Australia Means to Me, written for the Australia Day Council, and illustrated by Alan Moir. After listing his heroes, sacred sites, Australia’s greatest achievements and books we should read, our history teacher sets out ‘Five Things to Get Right’. They include immigration policy, the place of history in Australian education, more respect for the public sector, a more demanding approach to citizenship and a more relaxed attitude to our national symbols: the flag, the anthem and Australia Day. His tone is still clear and insistent, but can we do it? Of course we can.

Comments powered by CComment