- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Biding Its Time

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Alex Skovron has always been a clever poet, sometimes playfully so, more often seriously so. Skovron, who was born in Poland in 1948 and came to Australia, via Israel, in 1958, is steeped in the European intellectual tradition, though he wears his erudition lightly. Like almost everyone else, Skovron is troubled by the twentieth century: it seems to hang over the horizon of this book. He is also concerned about the nineteenth. As he says in ‘The Centuries’: ‘It is necessary to remind oneself / that the nineteenth century has never really left us: / it has been here all along, biding its time.’

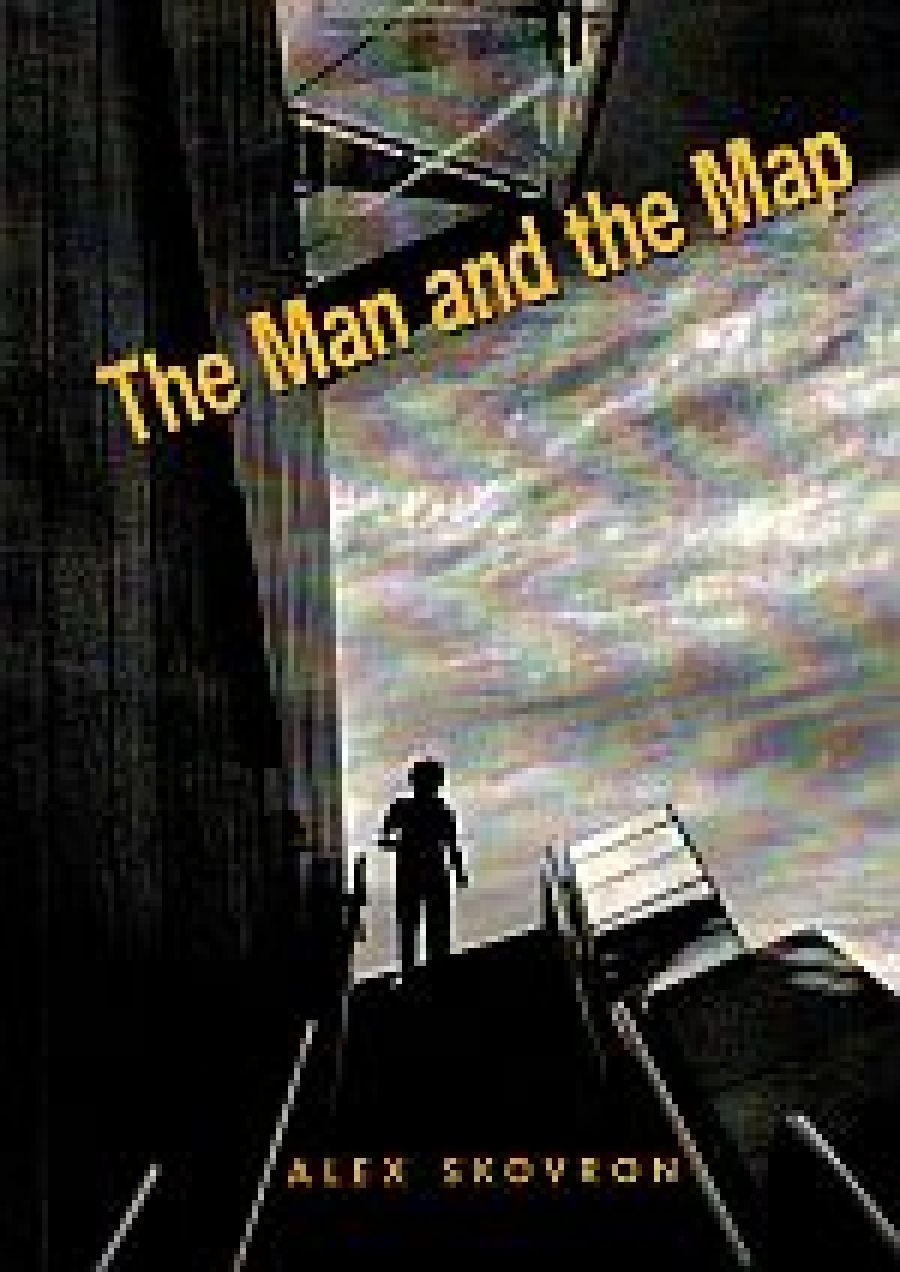

- Book 1 Title: The Man and the Map

- Book 1 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $21.95 pb, 135 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The tone is generally one of speculative bemusement. Why are things as they are? How is it so much of what we need to know is elusive? What are the deeper implications of all the things we take for granted? If this sounds ponderous, don’t be alarmed. Skovron rarely becomes too abstract or philosophical for his own good. His thought is tangible and rendered in visible symbols.

Perhaps the riskiest poem in this mode is ‘The Violinmaker, the Forest and the Clock’, which concludes Part I. Proceeding from the dictum ‘The universe makes no sense without music’, Skovron seems to suggest that the timeless meaning of music is to be found somewhere deep in the forest from which the violin’s wood was taken. ‘But we will not push beyond the forest, / the forest contains all we desire, / the city of time with its clocks and archways / can wait, continue, we are alone here: / we are alone with the murmuring forest — / we are complete, time is invisible.’

The universality of such an assertion foreshadows Part II. Here, Skovron is more explicitly concerned with philosophical and moral problems than in Part I, where he is content to imply them through his own autobiography. In ‘Vienna’, for instance, he investigates the paradox of how much good and evil have come out of that remarkable city. In five monologues from the viewpoints of Beethoven, Lenin, Freud, Hitler and Schoenberg, the poet investigates this mystery in some detail. Lenin, for instance, notes that: ‘the city cloys with its ancient glories, / the alleys are full of pimps and painters, / a war is coming, its stench is everywhere, / Europe will drown in the blood of artisans / impaling each other on colourful lances.’ Hitler has a different view: ‘The people will shout and the mountains cower / The nations will know a People’s power // A flood once carried the world away / I’ll show you Schicklgruber one day.’

In poems such as ‘The Guilt Factory’ and ‘The Man and the Map’, Skovron demonstrates a more Borgesian touch. The Guilt Factory is reminiscent, in dimensions and complexity, of Borges’s Library of Babel. They are both physical embodiments of human thought, feelings and complexity. ‘Nobody knows how far below the ground / the construction flows, how far into the sky / its elements incline — nobody has circled / the fac-tory from without, it is too vast.’

The title poem, ‘The Man and the Map’, is reminiscent of central European poets such as Miroslav Holub and Zbigniew Herbert. A man (an Everyman) is standing among ‘The dead flags / of a city square’, trying to read a map. A ‘larrikin breeze’ springs up, onto which he eventually releases the map, believing that he has found his directions. The narrator watches him observe the map’s flight, then sees the man ‘crumpled to a knee; immersed / in a howl I still can see’. Not a bad image for the human condition.

The ironic humour here is also a feature of many other poems in the second section. ‘A Marriage’ features a tormented husband who plays ‘the Emperor / without any clothes’. ‘Some Precepts of Postmodern Mourning’ is a light but not unloving satire of our current funeral rituals. ‘I Have Been Sitting’ is a Waiting for Godot-like take on our existence (‘waiting for a train / that will not arrive / from the opposite direction’). The book ends with a verse letter to the Jesuit poet Peter Steele, lightly comparing the latter’s ‘Roman’ religion to something less certain, ‘our native feel / for the absurd, our / love of paradox, our knowledge that there’s / nothing in the glass / beyond the glass that sees itself in us …’

The Man and the Map is a sort of intellectual report card, a statement from the student himself about where he has got to and what has brought him there. Skovron is an interesting and talented student of the human predicament.

Comments powered by CComment