- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

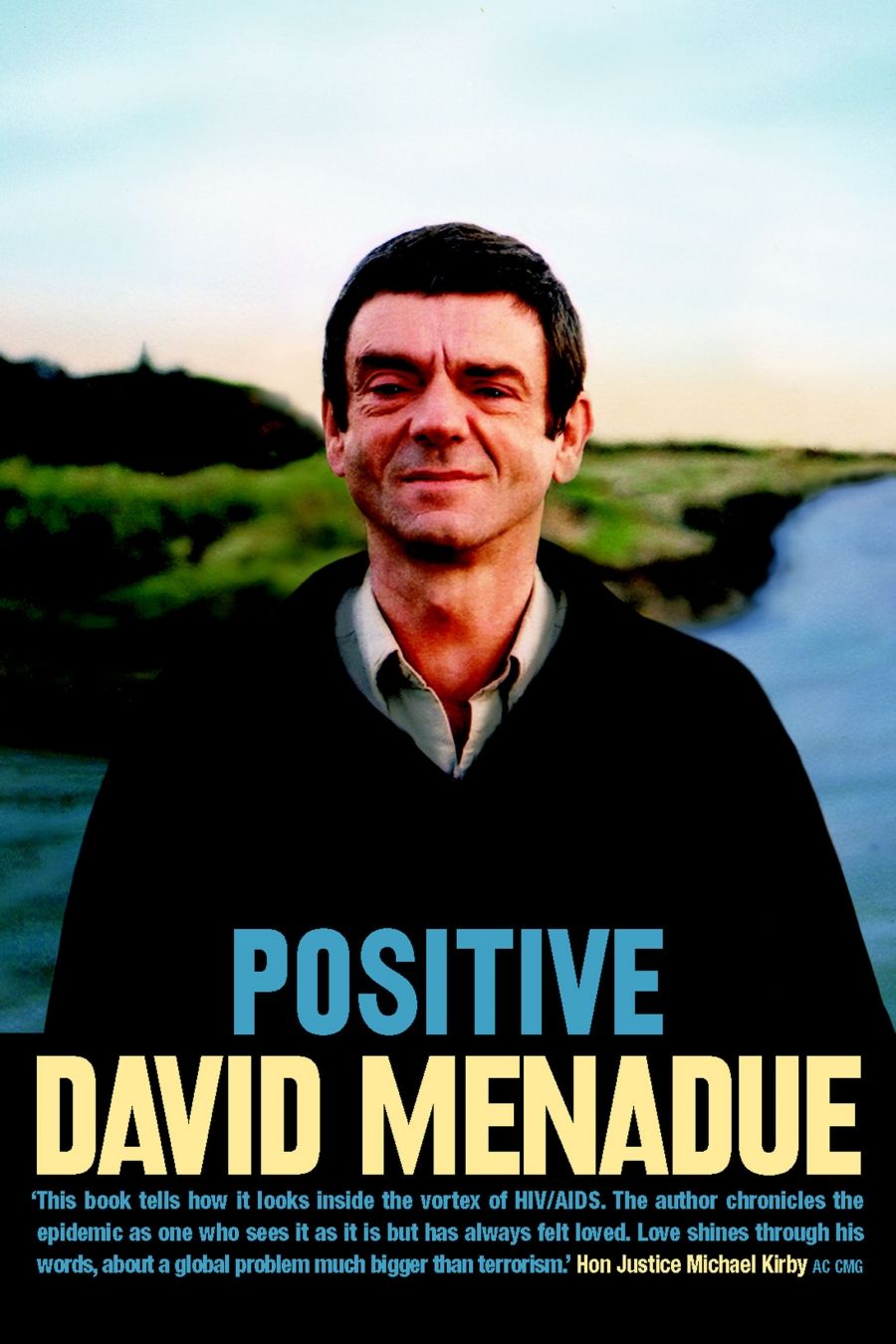

- Article Title: The Exceptional Optimist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the Australian world of HIV/AIDS, David Menadue is something of a legend. He tested positive to HIV in 1984, and first became ill with AIDS in 1989. This makes Menadue one of the longest-term survivors of an AIDS-defining illness in Victoria. As his doctors note, and as he reaffirms, not without a hint of justifiable pride, ‘this is a remarkable record … my survival is exceptional’. Equally exceptional is Menadue’s optimism. ‘I have always been an optimist,’ he writes, ‘and even in my darkest days with AIDS, I don’t think I ever gave up hope.’ This is how Menadue accounts for his longevity – a mix of optimism, hope and good fortune. The reader might also add courage.

- Book 1 Title: Positive

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $22.95 pb, 243 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

I worked with Menadue as a fellow board member of the Victorian AIDS Council (VAC) in 1998. During my term, I gained some insight into the fraught politics of Australian AIDS organisations. While new combination treatments had significantly curtailed mortality rates and markedly improved the lives of survivors like Menadue, the internal political and organisational battles continued to rage. In perhaps the least engaging chapter of this book, Menadue recounts the machinations of an earlier split within the VAC. To appreciate how consuming such divisions were, suspect that you have to know the players. Politics is always overdetermined, but throw in matters of personal health and survival, and you have the ingredients for bitter infighting.

When I knew him, Menadue, already a veteran of AIDS politics, conducted himself with an equanimity that others lacked. This composure is reproduced in the book. In surveying the personal, professional and political spheres of HIV/AIDS, Menadue is measured and thoughtful, without losing his distinctive voice. Something of a moderate, Menadue appreciates the integrity of direct political action and radical AIDS activism, whilst worrying about their productiveness. Never a political separatist, he writes of his distress and shame at the National AIDS Conference in 1992, when a number of HIV-positive speakers directed their anger at non-positive professionals. These were the bleakest of years – AIDS deaths in Australia peaked in 1993. For some activists, anger appeared the only recourse. Menadue, however, took a different approach: ‘I could never find it in myself to blame someone for my situation and kick out at the governments or AIDS Councils for failing to stop the carnage.’

There is a hint of another world and time in this sentence, when individuals accepted responsibility for their own fate, good or ill, without forgetting the worth of others. At heart, Menadue is a country boy. He was reared in rural Victoria and imbued with the values of Methodism and of a close-knit community. I say this with respect, having come from a similar background. Indeed, I imagine that many gay men of my generation will identify with some aspect of Positive, for this book is not simply an AIDS memoir; it is a chronicle of an era.

It is unwise in these pluralist days to speak of an archetype, but there is much in Menadue’s life story that embodies the recent remaking of male homosexual identity, at least in Anglo-Australian culture. A shy and bullied country boy, sexually uninterested in the opposite sex, finds himself at odds with a 1960s masculinity that put a premium on sporting prowess and heterosexuality. Through his intelligence and the expansion of postwar tertiary education, he migrates to the city where a freshly minted world of sexual and social opportunities beckons.

There he finds peers, in Menadue’s case the ‘Golden Nine’, and experiences the first surges of sexual and personal liberation. Posted back to the country as a high school teacher in 1974, he lasts two years before returning, ‘restless to explore my sexuality in the more tolerant and relatively anonymous city’. By now, the old camp world and the early gay liberation groups are superseded by a social scene of gay bars, nightclubs and sex venues, and it becomes increasingly possible for men like Menadue to live an openly gay life in inner-city enclaves.

This story has been told a number of times, not least by historians, but there is nothing better than the individual life to enliven the backcloth of history. Menadue is a charming storyteller, self-reflective and free of cant. He charts his uneven acceptance of his own homosexuality; the compartmentalisation of his life between work, family and sexuality; the exploration of sex in casual and fleeting encounters; and his ambivalence about romantic entanglements. Through his involvement in gay and trade union activism in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and with the good fortune of gay-friendly employment, Menadue grows in confidence.

The political conflicts of the period are woven into this personal narrative. Gay men and lesbians disagree over drag and the objectification of the male body as political cooperation crumbles. Left activists bridle against the commercialisation of gay life as the gap between activism and gay social life widens. Crops of radical homosexuals revisit these issues, especially on university campuses, but they had a particular bite in the pre-AIDS years. Menadue writes: ‘I couldn’t go for a night out at a disco without wondering if I was participating in a commercial/capitalist world with sexist, and misogynistic qualities.’

And then the tragedy of AIDS engulfs gay men. It’s hard to describe the terror of those early years. Menadue does this best when describing ‘the highly paranoid and bizarre thoughts’ that he suffered during a serious AIDS illness. But elsewhere it is as if Menadue’s equanimity will not allow him to plumb the despair of that first decade of AIDS. Maybe such forward momentum has been another factor in Menadue’s survival. Or as he puts it himself when describing the trauma of the early 1990s: ‘The only way I learned to cope was to move on and not dwell on the calamity of another death or the sadness of yet another funeral.’

The advent of protease inhibitors in 1996 has drastically altered the HIV/AIDS terrain. Even so, Menadue notes the toll that survivor guilt and continuing uncertainty have taken on his psychological well-being. Surveying the recent increases in infection and the fetishism of bare-backing, Menadue maintains that positive people ‘have to insist on safe sex and protect the other people’. Along with courage and optimism, this sort of personal integrity enlivens Positive.

It is a paradox that the most evocative representations of illness and death are often aesthetic. Perhaps beauty makes the unbearable tolerable. Positive, although engagingly written, is not a poetic book, but it is an important testimony of one man’s survival of a latter-day plague.

Comments powered by CComment