- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Anything Goes

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Anything Goes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Adib Khan’s fourth novel mirrors many of the concerns of his second, Solitude of Illusions (1997). Like Khalid in that novel, Martin Godwin in Homecoming looks back over a life that could have been better lived and a moral trajectory that has long since been deflected by one key event. Martin reflects on what could have been different and is tortured by what he sees as his own hypocrisy and cowardice. These attitudes to the past have repercussions for the future as his relationship with his son, again like Khalid’s, is characterised by guilt and misunderstanding. More broadly – and this is a feature of all Khan’s novels – there is a crucial disconnection between the older generation’s way of doing things and the ways of the next. This structure of present guilt and past actions (and inaction) results in novels that shuttle, sometimes a little awkwardly, between flashbacks and the present.

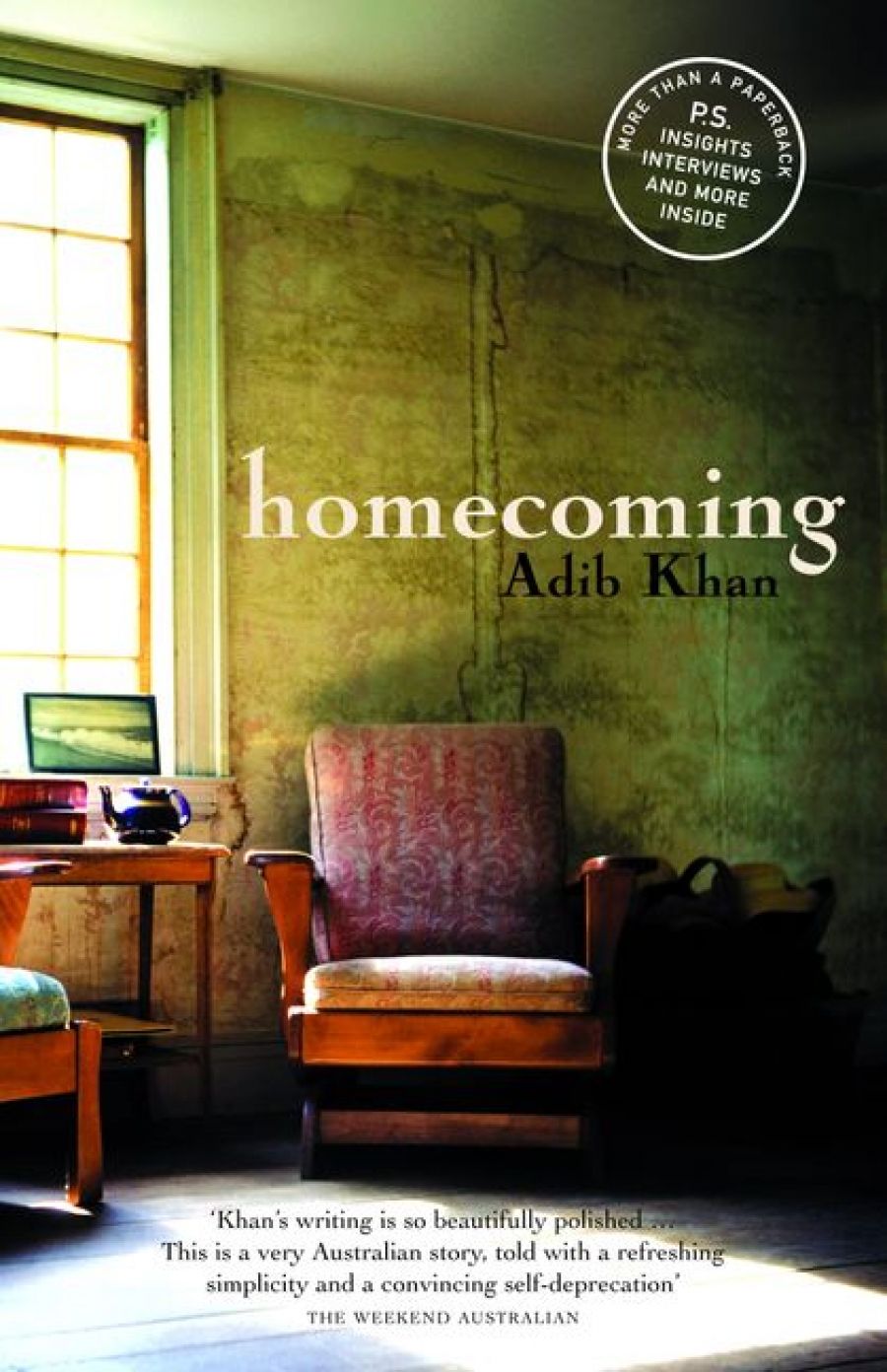

- Book 1 Title: Homecoming

- Book 1 Biblio: Flamingo, $29.95 pb, 255 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The setting is present-day Melbourne. Martin is a Vietnam veteran who has never reassimilated after the war. He is like a migrant in his own land. Although at the beginning of the novel he has married his pre-Vietnam girlfriend and had a son, Frank, Martin is alone, subsisting as a handyman, in trouble with the bank and in a difficult relationship with Frank. No fool, he does well in a range of university courses, but never completes a degree. He still has friends from his days in Vietnam, but these relationships are edgy and difficult, not the stuff of reminiscence or easy bonding.

In the novel’s present (marked by the use of the present tense), Martin faces a number of decisions, the foremost being how to react to Frank’s partner and whether he should follow Frank to Daylesford. The narrative often backtracks to his time in Vietnam and to subsequent events. It becomes clear that, apart from the general experience of warfare and killing, there is something specific at work in Martin’s memories, an issue that he has not even revealed to his psychiatrist.

Given what is well known about Vietnam – the rape, killing and plunder of civilians – this trauma will not surprise most readers. It is not structured into the narrative as a great mystery. But it is something that Martin needs to articulate, even if that moment of articulation will not involve his therapist. As a result, the narrative is not essentially plot-driven. Although some decisions do have to be made, this is not a plot driven by goals but rather by a constant shuttling between reminiscence and present responses to the past.

Homecoming is a significant novel in terms of its author’s trajectory. A novel of ideas with a fully Australian focus, it moves him from the niche of slightly magical-realist Indian tales into the mainstream. It is bold, often convincing and always readable. As a meditation, however, it doesn’t entirely convince. The relatively low-key plot is not a problem, but it does contribute to a sense that the solutions are a little pat. In the novel’s moral scheme, a trauma brought out into the open is a trauma dissipated. This, after all, is what Martin’s therapist is trying to do for him via the talking cure. At the end of the novel, Martin is seemingly ready to pick up the pieces of his fragmented life.

Early in the novel, we learn the following about Frank: ‘The young man appears to have no awareness of cultural boundaries, nor does he allow himself to be guided by tradition. Frank dabbles in whatever appeals to his craving for the exotic.’ He is open to Buddhism and the whole package of New Age solutions. Martin clearly disapproves. But for Martin, in turn, things get better when he relaxes, visits the ashram that Frank goes to and dabbles in the exotic. Anything goes, after all.

That makes a solution to years of guilt a little over-simplified. In any case, by the time we do learn about the central trauma, the thing that Martin can barely confront, the narrative has set us up to forgive him and to see that he is not remotely the culprit he thinks he is. The blame, it’s already clear, lies elsewhere. We have also learnt that whatever Martin did back then, he has made up for in his postwar atonement. The narrative dice are loaded in Martin’s favour. Most of the other characters, and eventually the readers, can see that Martin is simply not that bad a person.

The satisfaction of a too-rounded ending detracts from the novel’s ability to convince as a meditation on post-traumatic stress. It is hardly the first novel of ideas to make things seem simple on paper, however. Like Khan’s other novels, this one is expertly told. It marks an interesting new shift in his work.

Comments powered by CComment