- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: KALEIDOSCOPE

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Those Who Remain Will Always Remember is a fitting successor to Paperbark, the Muecke, Davis, Shoemaker, Mudrooroo anthology of a decade earlier. Though it is a regional publication, restricted to Aboriginal authors from Western Australia, it follows the same catholic principles of inclusion that made Paperbark a book of its time. Its editors Anne Brewster, Angeline O’Neill, and Rosemary van den Berg provide a kaleidoscopic image of Western Australian Aboriginal life in assembling writings which include critical essays, cultural-political statements, prose fiction, life histories, personal testimony, interviews, and poetry. Importantly, these disparate genres leave the reader with a sense of the editors’ unity of vision rather than ad hoc opportunism.

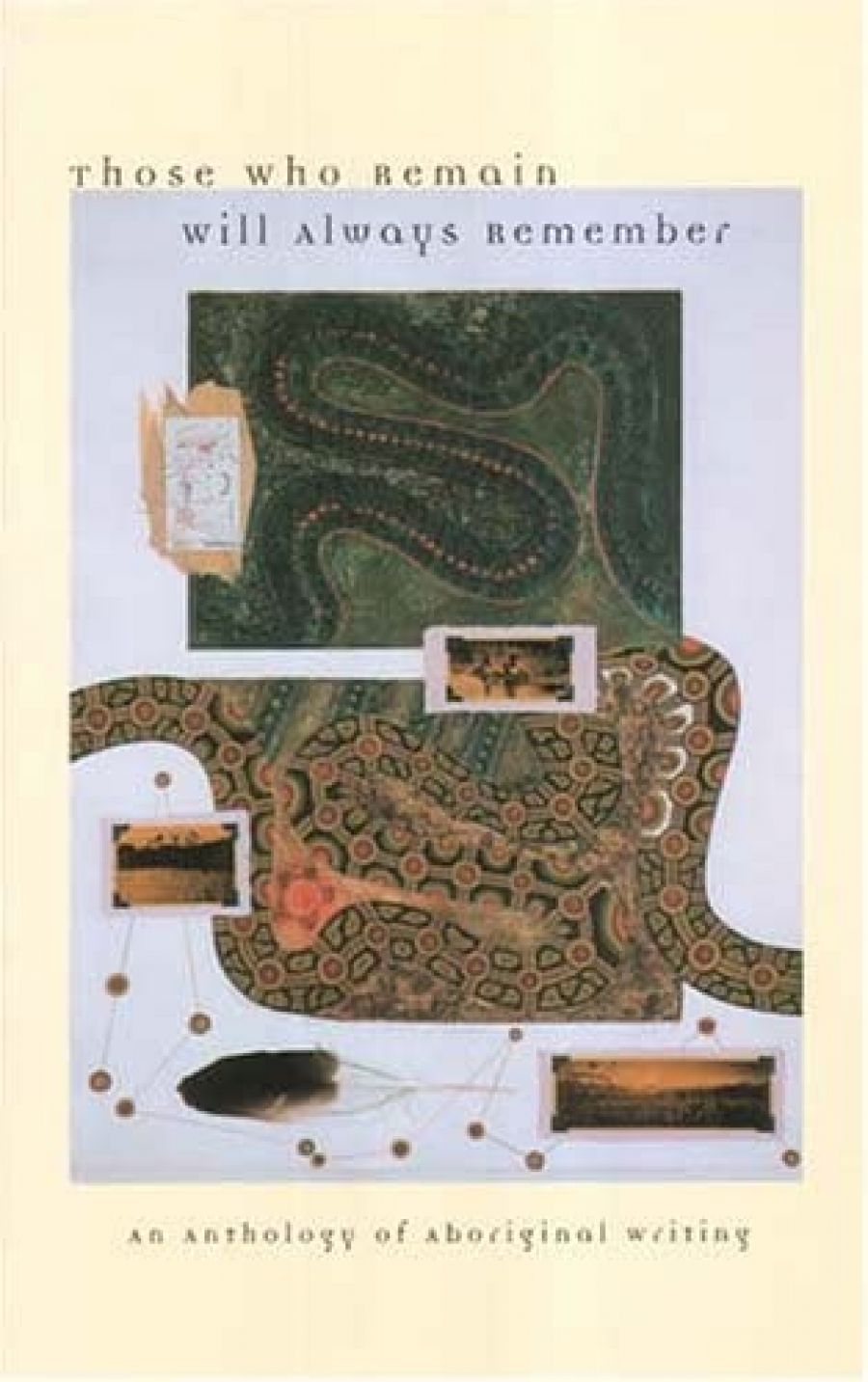

- Book 1 Title: Those Who Remain Will Always Remember

- Book 1 Subtitle: An anthology of Aboriginal writing

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP, $19.95 pb, 328 pp

The thoroughness with which the editors essayed their task is shown by the fact that around half of the contributors have never published before. But as well as this breadth of material, judgement is shown in the choice of individual writings. These range from Robert Eggington’s cogent but implacable analysis of cultural appropriation ‘Jangga Meenya Bomunggur (The Smell of the Whiteman is Killing Us)’, Rosemary van den Berg’s description of the hardships of a ‘mixedmarriage’, and Patricia Mamjun Torres’ atmospheric ghost story, ‘Bilyurr-Bilyuu Jarnu, The Red-Dress Woman’, a tale which unites traditional belief and the supernatural with childhood experience. Poetry, often a weak point, is excellent here: the anthology opens with Fred Penny’s sardonic ‘The Urbarigine’ and moves on to the pathos of Barbara Stanner and Lloyd Riley. A sub-genre which the book makes effective use of is what I would call ‘impressions’. These are very short prose pieces, of sometimes not more than a hundred words. Ever wondered what it’s like to be a squatter in a public park? Walk the line as an Aboriginal police aid? Farewell a man about to do time? Mary Champion, Helen Lockyer, and June Williams give exact descriptions of realities and psychological states which many of us never experience.

A noticeable feature of many of the poems and narratives is the voice of the author which comes through without affectation or vanity. This is evident in fifteen year old Chantelle Hanson’s ‘The Story of Joanne Grey’ which represents a teenager encountering grief, learning to trust friends and relatives and turning away from no-hopers. Lorna Little’s ‘The Miracle’ seems to offer conventional pietism, but this gives no hint of the cleverness and subtlety of a narrative which without effort moves from an exposition of Nyoongah families and the seasonal work of potato digging to a story about alcohol and misperception. The sudden twist in the ending of this tale, also notable in Kristy Jones’ ‘Welcome to the real world’, reminded me of the structure and affect of Barbara Baynton’s ‘The Chosen Vessel’.

Allan Knapp writes of the empowerment he experiences as a boxer overcoming fear and winning a fight against a tough opponent. But this resonates with his portrayal of himself as a small boy, the victim of ferocious bullying by one of his sisters. Another perspective on rude masculinity is provided by Rosemary van den Berg’s mischievously titled ‘The Royal Show’, the story of a visit to the Show by a group of young Nyoongar women. The noise of the boxing tent attracts their attention: a drum is being beaten and insults and challenges are being traded back and forth between a spruiker and men in the crowd of onlookers. Some of the tent boxers are Aboriginal and when they see the girls they begin to flirt with them, shadow boxing vigorously and grinning. Too late the fighters realise that the girls’ appreciative giggling owes more to the view provided by the baggy legs on their boxing trunks rather than their athleticism.

What do you make of someone who writes, ‘I honestly believe today that those religious people were right; what a stupid child, and into a stupid man he grew.’ Alf Taylor’s description of himself is explained when we realise that he was one of the Stolen Generation, and his autobiographical narrative is marked by the bleak but resilient humour of the survivor: ‘Whatever challenge I am confronted with in life I give it my whole. Even waking up now, in the mornings, if I’m not pissed or stoned I greet the day full on.’

These are just a few examples of the depth of this collection and if I had to choose the strongest piece it would be Pat Dudgeon’s ‘Four Kilometres’, the story of an Aboriginal man and his dog jogging at night. Initially his thoughts are on his dog and the New Age devotees who covet Aboriginal spirituality. But as he jogs on, the layers of self peel back and he begins to consider his own position as a middle-aged bureaucrat in the Aboriginal industry (his own words). All this is interspersed with encounters with families and teenagers as he runs. Dudgeon’s story is one of the most effective and complex presentations of contemporary Aboriginality I’ve come across.

If I fault the editors on any point it would be the introduction. Instead of a clear and simple exposition of the collected material, and some advice on how it might be read, the editors provide a foreword which a non-academic would find hardgoing. Occasionally they fall into the jargon of the academic grubber, as in

This realisation represents a complex nexus; it is at this point that the false consciousness of the colonised disperses and the recognition that (post/neo)colonial power can be challenged is born; it also constitutes a moment of mourning; the point at which an awareness of loss is intensified.

Reading Those Who Remain Will Always Remember is a pleasure not a reconciliatory duty, and the introduction should have reflected this. But irrespective of this criticism Brewster, O’Neill, and van den Berg have coordinated an important text; the extent to which an anthology works can usually be attributed to the editors and in this case the trust shown in them by the Western Australian Aboriginal community has been amply repaid.

Comments powered by CComment