- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

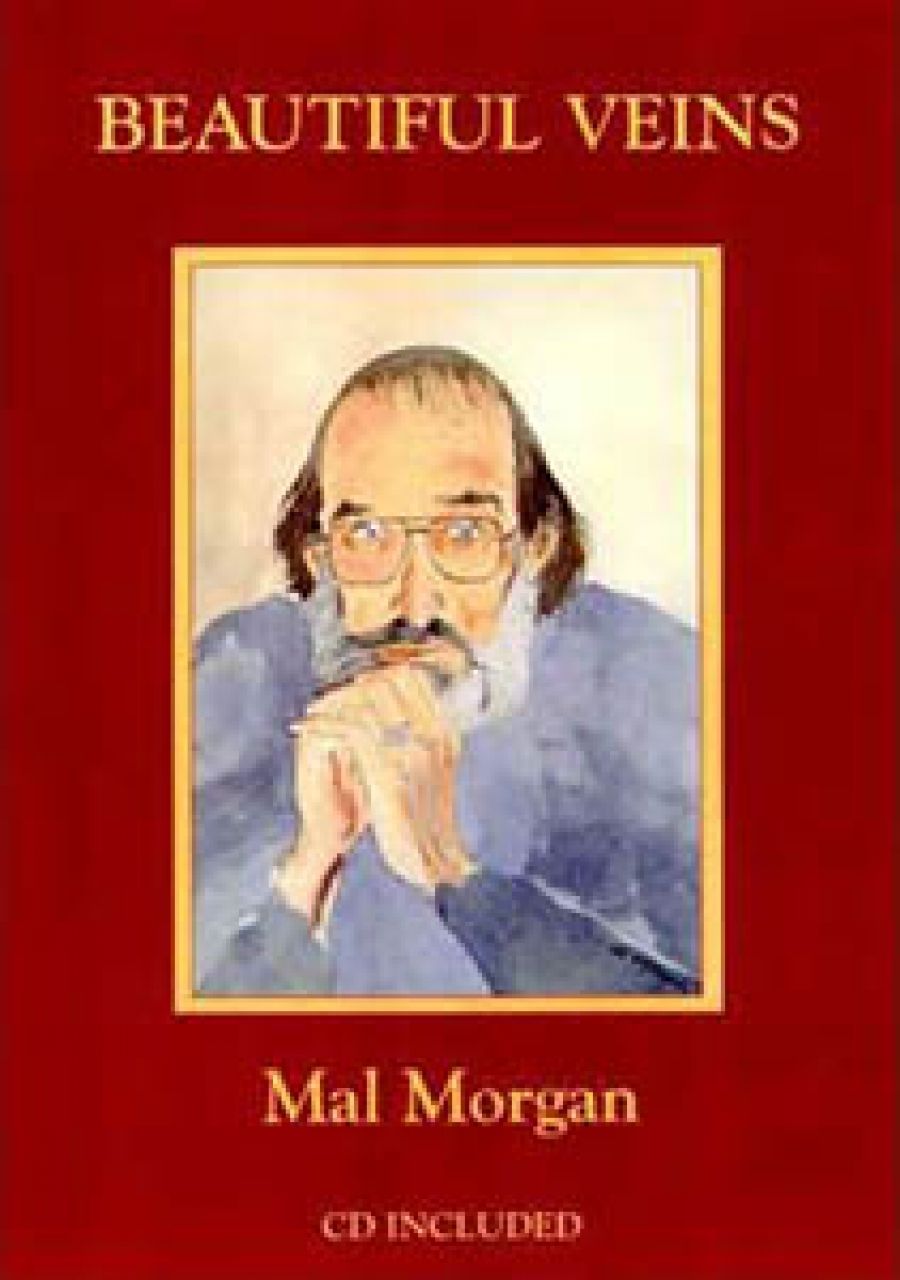

In a note to the reader, Mal Morgan tells us that this last, posthumous collection Beautiful Veins – it comes with a CD selected from this and other work – was written during the five months after his being diagnosed with lung cancer. They’re note-taking, note-jotting poems. A sense of someone hurriedly trying to account for and describe his response both to the diagnosis and to the radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatments which ensue is uppermost. Strong, disturbing, they’re often ‘I do this, I do that’ (Frank O’Hara’s phrase) confessional poems.

- Book 1 Title: Beautiful Veins

- Book 1 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $18.95 pb, 64 pp

- Book 2 Title: Fighting in the Shade

- Book 2 Biblio: Hale and Iremonger, $18.95 pb, 72 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Archives_and_Online_Exclusives/fighting in the shade.jpg

At one point, reflecting this urgency, he comments that, having only written nineteen poems ‘since it began’, he needs more to make a book. Sometimes uncomfortably, you’re never unaware that Morgan’s made a deliberate choice to write this disastrous moment of ill-health into a life-and-death poetic moment. What results are short narratives which talk well and read fast – whether scenes from the clinic, or observations about and thoughts directed to friends, or scribbled moments of deep anxiety in the middle of the night. ‘The dead have no choices,’ he says in ‘All On a Sunday Afternoon’, including the choice of sitting and meditating ‘the slow movements of a swan’. Beautiful Veins is a collection which can make the fast choices of hastily grabbing things at a point of crisis as well as the slow, meditative choices of looking at swans. Similarly, in another short poem, ‘No God’, he concludes:

… No god just the

poetry of things a work in progress

colossal and true enough.

Here again, Morgan’s death experience is interpreted as an urge towards a poetry at once both spontaneously transient as well as ‘colossal’ enough.

To a degree, of course, the reader has little room to move in response. How do you discuss the pathos of this situation? (Anyone who has lived with someone terminally ill knows the full force of this question.) In poetic terms, how do you know that these are not just any but good reports on extreme experience? How, for instance, do you turn over in your own mind Morgan’s question, in ‘Cheder Painting 1930s’, ‘… why / at death should this night be different / from all other nights?’ The immediacy, the sense of willed reportage, are so intense that such freedom of response starts to seem irrelevant, even tasteless. ‘I have to write this down,’ Morgan notated in a hauntingly sad, insomniac 3 a.m. poem entitled ‘Unreal’: the reader is given no choice but to read what’s said at an ultimate level of face-value. For Morgan, the threatened and terrifying moment of dying was imposed on him as a moment with no ‘in-between’ or level of intersection.

In the poem ‘Death in Shining Armour’, for instance, it’s the moment where the radio or the CD is on and ‘You just don’t / hear it stop’ or where one day you’re in someone’s kitchen and then, as he puts it, ‘you’re not.’ Neither the reader nor the poet can summon much reflective space in this matter of directly accounting for an experience as negative as fighting off cancer. He is, as he puts it in ‘The Witness’, ‘pain’s witness’ and as such ‘I am / not my cancer not my body.’

It’s exactly this mixture of undiluted anxiety and an upfront matter-of-fact descriptiveness which so disturbs in this collection. There is, I guess, almost a genre of poems which deal with the country which is, in Plath’s phrase, ‘as far away as health’ – David Campbell, Gwen Harwood, Jennifer Rankin, and Philip Hodgins all wrote unforgettable poems about the experience of cancer. Each poet who has this appalling theme dumped on him or her has inevitably to deal with what Susan Sontag long ago called the ‘scandalous’ nature of cancer as a subject for poetry: it seems, she says, ‘unimaginable to aestheticise the disease’. These are the words which Hodgins used as an epigraph to his poem ‘Ich Bin Allein’ – one of the most stark, emotionally powerful poems in our language. Each of these writers had to deal with what can and cannot be said about this ‘unimaginable’ intrusion into, and reconstruction of, the self. Each had to test to the limits the constraints of pathos, of poetic formality and aesthetic response. It’s here, in this no-man’s land between everyday health and illness-driven anxiety that the late Mal Morgan’s up-front poems cut through.

To talk of experiences which break through traditional aesthetic modalities is, by no means, irrelevant to Peter Kocan’s latest collection. A writer who established his work as ‘reportage’ on extreme experience, Fighting in the Shade is a book largely about how (as he puts it in the final poem dedicated to Les Murray and Hal Colebatch) ‘to hold the line’. The line he refers to is (literally) Hadrian’s Wall – historic limit of a declining empire of civilised classical values – as much as it is also the regularised, neo-formalist line in which he chooses to write nearly all the poems in this new collection. Simple diction, cast in rhyming five-foot quatrains, is the staple of Fighting in the Shade. The very title, a reference to doomed Spartans at the battle of Thermopylae, implies a number of rather beleaguered classical aims.

Where these are addressed directly and where, accordingly, a degree of irony is allowed into his affable, regular verse forms, they make for interesting poetry. ‘Mentioned in Passing’, a poem about overhearing a conversation about a violent death, ‘Signs’, ‘Cowper’, a poem about ‘the abyss of the insane’ beneath everyday coherence, ‘Trapped’, an eerie poem about soldiers stuck in an armoured car in a city where their side have already evacuated, ‘On the Laying of Wreaths…’ a peculiar but challenging poem about the hypocrisy of celebrating the Port Arthur dead: these pieces let the formal, somewhat ‘Housemanesque’ (a title for one of the poems) clarity of the language give way just enough and just at the right places to create moments in experience and insight.

The paradox is that Kocan’s formal means mostly don’t give him enough room for complex and energetic poetry. They lack precisely what the ‘classical’ and traditional verse he admires abundantly has: polyphony, more than one voice, up-to-date music, a freedom to take risks. Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, even Tennyson and Hardy at their best, did not write verse where syllables slot into place like ratchets into cogs. Try Milton’s ‘At a Solemn Musick’, for example. The beleaguered, thin, technical values, the narrow, despairing themes (‘And so we will continue till the day/ We find it [i.e. a new Holocaust] towering upon us here’) grow as much from within the poetry as from any social or ‘politically correct’ oppression from without. At their weakest, the pieces end up sounding trite, rather than epigrammatic. Their traditional, self-consciously simple manner comes across all too often as an overly controlling ‘sign’ in exactly the way a cultural critic would revel in explaining: it stands for – and too often, too generally – civilisation, common sense, the threatened art of poetry. But can it? Can anything be so simple, so transparent?

Kocan’s new poems trade restraint and smallness in relation to what he sees as an ‘era (gone) from bad to worse’; but given the ‘enemies’ all too apparent in the book, the poetry often lacks, dare one say it, anger. If Morgan’s last poems run the risk of only being deeply courageous evidence of a crisis of compulsion – challenging a non-poetic ‘unimaginable’ fact – Kocan’s securely held line seems too dwarfed, too heritaged to matter that much.

Comments powered by CComment