- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Setting Agendas

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The British exploration of the Pacific Ocean between 1764, when Byron sailed, and 1780, when Cook’s third circumnavigation concluded, and the colonisation of New South Wales from 1788 onwards, effectively set agendas in discovery and settlement which France and Spain had to emulate if they were to continue as Britain’s imperial rivals.

Spain’s effort to match the British agenda was spectacular, but short-lived. The expedition under the command of Alejandro Malaspina that it sent to explore in the Pacific and to report on the state of the Spanish empire (1789–94) was perhaps the best equipped of all the grand eighteenth-century voyages, but its commander fell victim to political intrigue on his return; and oblivion settled over its results. (Only now are its journals, artwork and collections being fully analysed and published.)

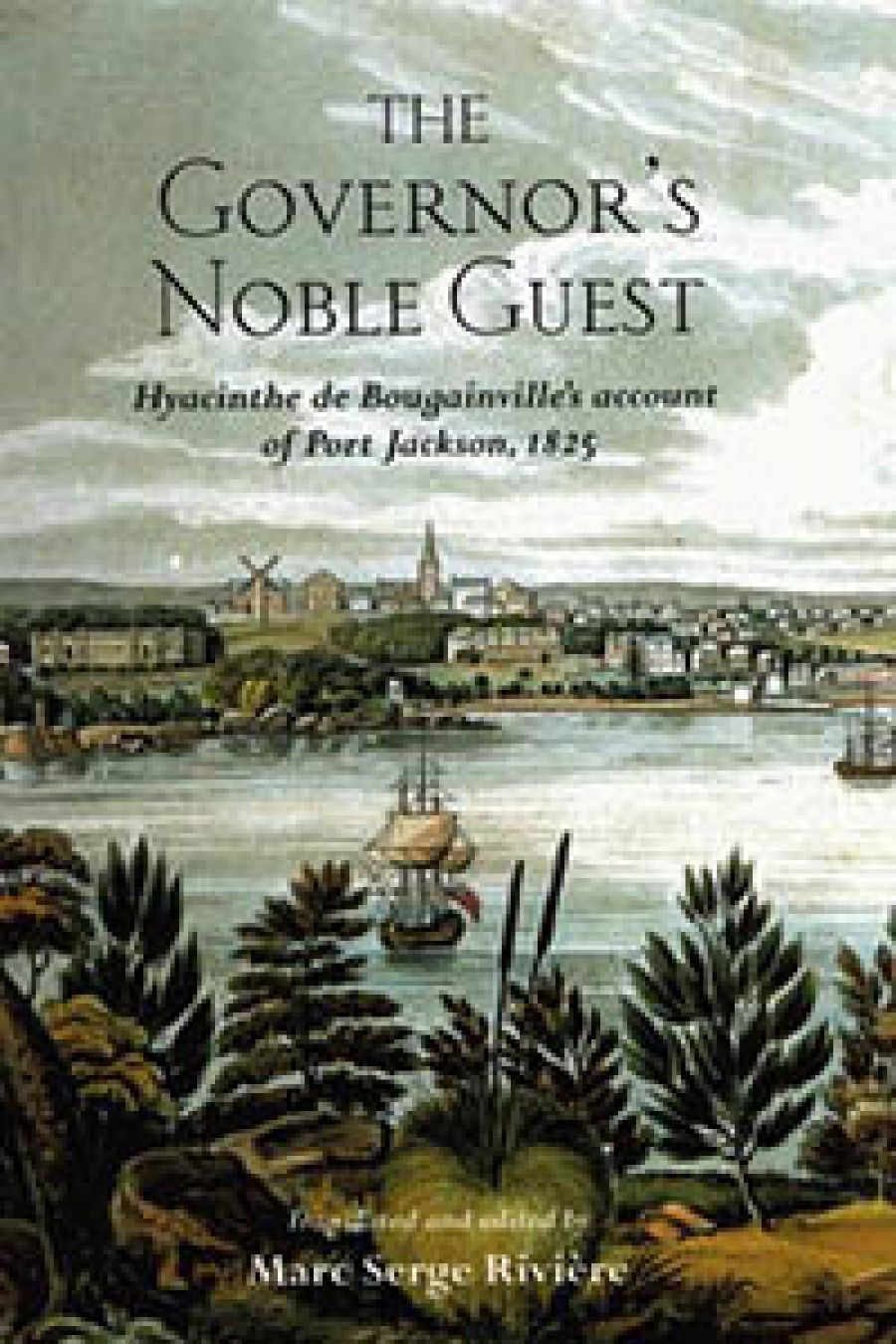

- Book 1 Title: The Governor’s Noble Guest

- Book 1 Subtitle: Hyacinthe de Bougainville’s account of Port Jackson, 1825

- Book 1 Readings Link: Miegunyah Press, $49.95 hb, 292 pp

On the other hand, before, in the intervals between, and after the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, the French made strenuous efforts to match the British. From the mid-1780s into the 1840s, various governments mounted a series of major expeditions intended to explore further in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, to gather scientific and ethnographic information; and – equally as important – to establish a French imperial presence in the southern hemisphere The nature of voyages of exploration underwent two significant shifts of emphasis in this period. First, the focus changed from the great oceanic sweeps designed to locate islands, coasts and places of refreshment, and to establish the general features of wind and current systems (Cook, Laperouse and to some extent Malaspina), to close coastal surveying (Vancouver: 1791–95; Baudin: 1800–04; Flinders: 1801–03).

Then, with coastlines largely charted, greater emphasis was placed on scientific reconnaissance and collection. With the modern scientific disciplines emergent at the turn of the nineteenth century, and with instruments growing in number and refinement, the explorers attended increasingly to zoology, botany, geology, hydrography, and meteorology. At the same time, there was also a greater emphasis on acquiring detailed knowledge of ethnology, anthropology, and human physiology, and physiognomy.

Yet it was naive to suppose that these national expeditions proceeded only in the cause of disinterested science - and in any case the evidence is clearly against it. There were distinct commercial motives behind Cook’s third voyage; Laperouse and Malaspina were each instructed to· report on the social, economic and strategic conditions of rival nations’ colonies; Baudin alluded darkly to a hidden, secret instruction.

It was different for Hyacinthe de Bougainville’s voyage (March 1824–June 1826). The French Minister of Marine pointed out to him that while peace presently prevailed, in the event of war breaking out, we must plan ahead to be in a position to pursue the best course for France. ‘If England were to become our enemy, the French navy may as a result of our forward planning enjoy considerable success ... we must have at our disposal precise information concerning the fortifications of the targeted positions.’

Accordingly, Bougainville reported that while Sydney was the ‘hub of the vast English territories in the southern hemisphere’, and Port Jackson ‘one of the safest [harbours] in the world, [which] could easily provide a haven for all the warships of Europe’, defences were ‘so weak that they are almost negligible’. On the other hand, he saw that ‘it would be easy to make it almost impregnable from the sea at little expense’. The reason for the British not having done so was clear to him: ‘They know that their fleet, which rules the seas, is the best protection for their colonies.’

The colony interested foreign officers for other reasons. Our historiography has bequeathed us images of dearth, depravity, and a ‘fatal shore’. But the simple fact is that the progress of the convict colony was practically unexampled in the history of European expansion. Spanish and French explorers came to it expecting to find a ramshackle outpost of empire, and found instead a thriving centre. Bougainville observed that Sydney ‘is an excellent port of call; the climate is healthy and supplies are abundant and of the highest quality, albeit somewhat expensive’. The British, he saw, had ‘transformed a country that was uncultivated and wild into a fertile and prosperous land’.

In The Governor’s Noble Guest, the editor reprints the bulk of Bougainville’s notebook entries for his time in New South Wales; and the relevant portion of his account of the voyage published in 1837, which incorporates the results of his wide reading about and reflections on the colony. Hence, we have only glimpses of the expedition’s scientific work, in the officers’ attention to the geology, botany, zoology and ethnography of New South Wales.

By the time of this, Bougainville’s second visit – he had been on Baudin’s expedition in 1802 – the convict colony had become prosperous. Especially indicative were the circumstances of those civil and military officers who had arrived between 1790 and 1810 and turned to farming. By the mid-1820s, these had acquired wealth sufficient to enable them to enjoy townhouses and to be building country seats. Prominent among those whom Bougainville and his officers were entertained by were the Macarthurs {Parramatta and Camden), the Blaxlands (Newington), John Jamison (Regentsville), John Oxley (Kirkham), John Piper (Henrietta Villa), Samuel Marsden (Memre Brook}, William Cox (Clarendon).

Bougainville’s notes tell us much about these people and the way of life they had created on the Cumberland Plain. Cox, for example, was manufacturing cloth and shoes, sugar and wine. Jamison was building a ‘small castle’, about which were ‘large fields covered with the debris of corn ears ... and lush fields of wheat’. D’ Arcy Wentworth had seven hundred horses, the Macarthurs ten thousand cattle. The garden at Government House, Parramatta, was abundant with citrus fruits. Bougainville’s portrait of Marsden with his Maori retinue is surprisingly favourable; and he describes a formal kangaroo hunt organised by the Macarthurs without irony.

Bougainville was also alert to the tensions between the Exclusives and the Emancipists, and to the growing clamour in the colony for a representative legislature and trial by jury. His descriptions are both interesting and informative.

The text is well-edited; and in its production and illustrations, this work exhibits that excellence we have come to associate with the Miegunyah Press.

Comments powered by CComment