- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unsound Practice

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When I was still a jot at uni, a medical student friend stumbled late out of her latest lecture and reassured me. And then she assured me, ‘It was horrible! We had slide after slide of some dead smoker’s lungs. And they were disgusting! I’m gonna be sick! Give me a cigarette!’ That’s when I first understood that ‘smoking’ was not ever going to be a straightforward subject.

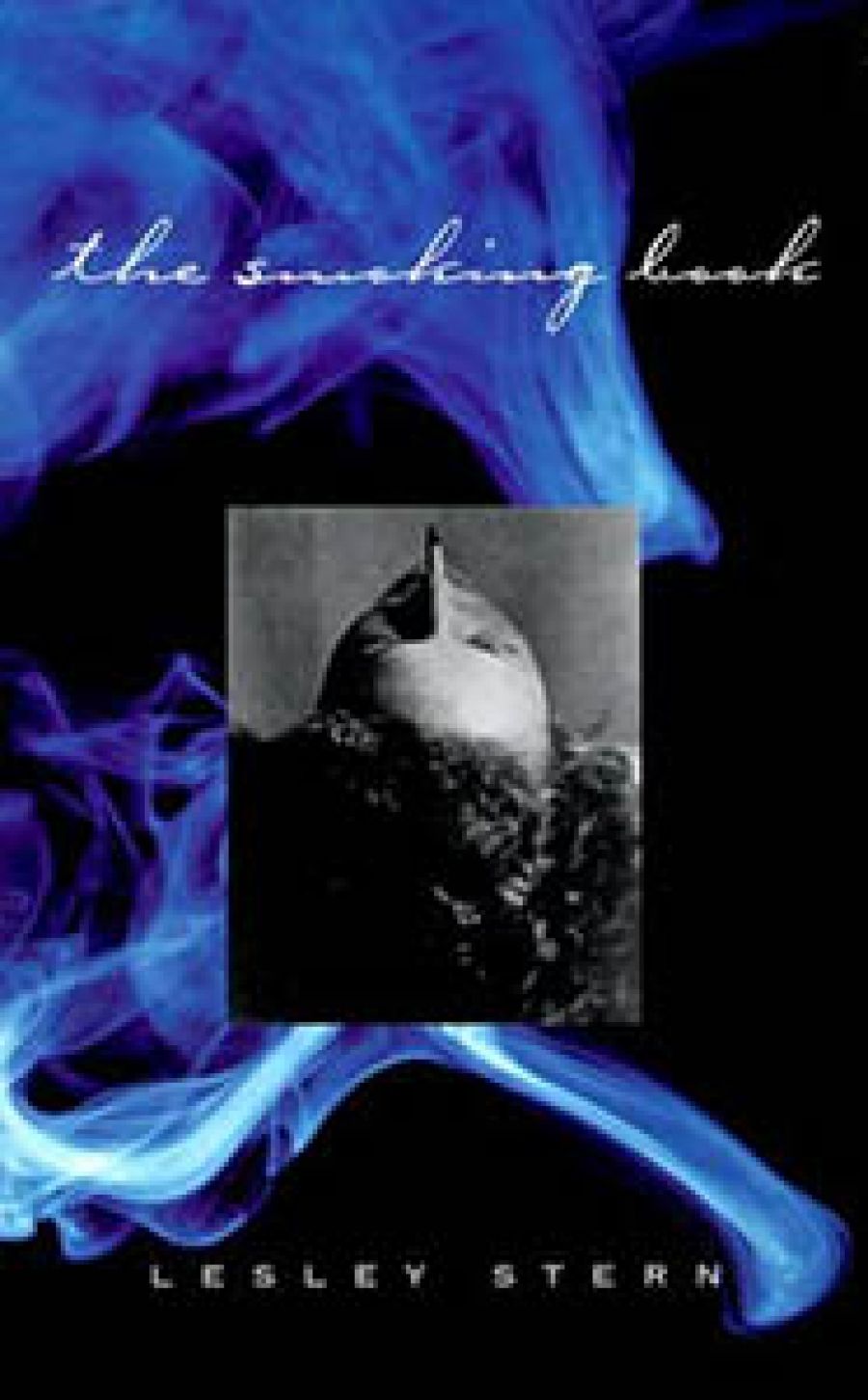

- Book 1 Title: The Smoking Book

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, $22 hb, 238 pp

I speak as a smoker (as is Stern herself), and let this be marked as the only point of similarity between Stern and say, a puffing John Elliott, in all his corrupted swaggering. And me too, me too! The man is even unhappy paying taxes, even for social services, like education, welfare, health! Society, they call it. He’s happy enough for you to pay a GST on ABR.

It’s the latter, the moral connotations of such an emotionally dimensional practice that Stern takes on, as economies, fiscal, and political as well as emotional. Now we all know that economies of any sort involve oppressive acts. Stern posits smoking fascinatingly as an act of resistance too, and signifying even eventual liberation (as all resistance must). This is absolutely not a ‘how to’ or ‘why one would or should’ book; for one of that ilk, please contact Philip Morris or some other tobacco super-comprador. This is a ‘what is it’ book, that situates smoking into its proper complex of social practices and motives, that well include grief, of a personal, individualised nature right through to its macro-scaled variant, suffering that is entire peoples wide. Smoking is regarded as a suitable metaphor, a useful one, for exploring the theme of that relationship between the conquered and the conquistador, be the latter an army of invasion intent on plunder, a tobacco merchant, or just your lover ... or your parent or your sibling. Smoking is presented as a marker for where grief might exist at the same time as it is represented as an act of defiance, a resistance to obliteration. This is not an uncomplicated book.

And what a giraffe of a book. The book, galloping elegantly across the wide landscape of subjects it interrogates, complicated in its beauty, involves fifty-four episodes or stories of ranging hue, all linked. She offers glimpses of the tobacco trade in the former Rhodesia, describes the tobacco sales rooms in Zimbabwe, where billions of dollars’ worth of tobacco are sold annually ... she tells of explorers’ and invaders’ forays in Africa ... she dips into Barthes and Derrida as well as opera, art and films. And much to my added pleasure, she fictionalises too, she dramatises on an achingly human scale, offering us memoir and other genres of dramatic, more subjective, personal story.

One of my own favourite ‘episodes’ (and I’m happy to report that it is difficult to choose a favourite among so many favourites) is titled ‘A Fishy Smell’, a short-enough lyric of surprisingly epic scale in which the book gallops us through London bus travel, the possibility that there is no future, the aroma and other sensory textures of tobacco, the sound of Shona song and childhood, the persistence of memory, just like an addiction, an angst of existential proportions, fatherhood and other proprietorships as insinuating as ash, Levi Strauss on the ‘culinary’, book-burning, Luther, dissidence, resistance, smoking and finally, fittingly, entropy as human condition, indistinguishable from that of a star ... or a cigarette.

That’s just my favourite of favourite moments. The book, all impossible limbs and neck, unexpected, bulbous joints, always threatening to break and sag under its weighty, even apparently ungainly structure, is finally graceful and fluid, and only apparently impossible. Just like the awesome giraffe. It is a difficult book, neither one smooth genre nor another, a hybrid, a melange, an elegant sum of surprisingly comfortable parts. No bad thing in itself, not at all, not in a world of books that are all the same, that celebrate sameness.

So the South African-born Stern is a moralist, a writerly animal of political bent, just like grandfolks Swift, Orwell, Didion et al, though she is not as practised or predictably fluent a prosodist yet. Yet. Not least because she is trying something so generically different, so challenging that attention to plain old rhetoric suffers a tad, I suspect. But there are many passages that literally sing. What a relief! The tide threatened me with the possibility that this was just another sludgy, decadent, fin de siecle, lifestyle-sodden, new ageish waste of tree. The sum is greater than the parts. So are some of the parts greater than others. Well, there are fifty-four of them. The scale of the book, its ambitiousness, its idea, are all breathtaking, as its poetry mostly is. Read this book. Or smoke it ... in its parts, a bit at a time, for a prolonged pleasure’s sake.

Comments powered by CComment