- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: Rolling Column | Alison Ravenscroft on 'Jackson’s Track: A memoir of a Dreamtime place' by Daryl Tonkin and Carolyn Landon

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

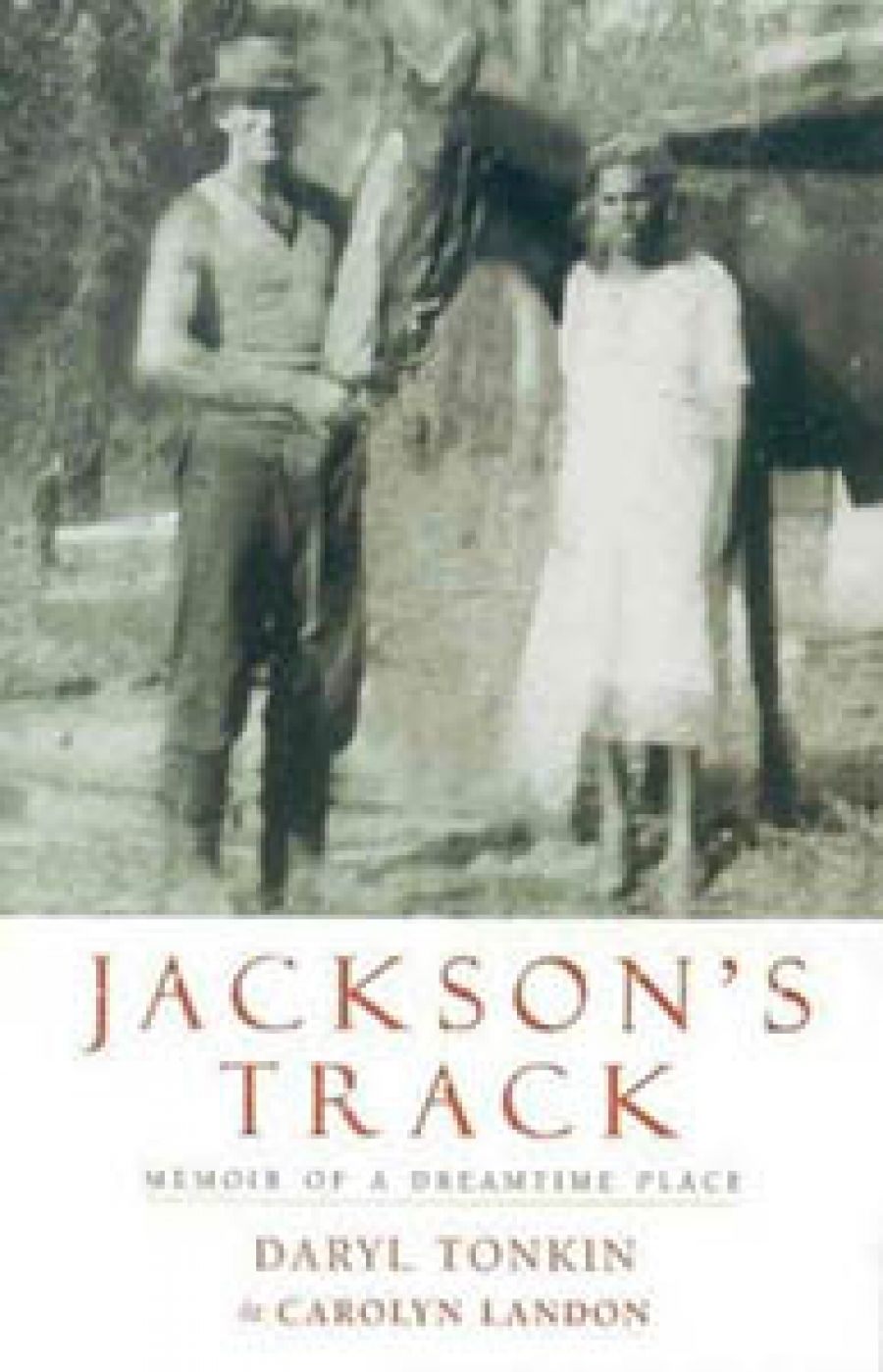

When I first picked up a copy of Jackson’s Track: A memoir of a Dreamtime place (Daryl Tonkin and Carolyn Landon, Viking 1999), I expected to find the life story of an Aboriginal woman. The striking cover photograph the 1940s of Euphemia Mullett in high-heeled shoes and light summer dress, standing beside a white man and his horse in a forest clearing suggested it, as did the reference to the dreamtime in the book’s title. I soon discovered my mistake. Jackson’s Track is instead the memoir of the white man in the photograph, Daryl Tonkin, who owned land and a timber mill at Jackson’s Track, West Gippsland, for over forty years from the mid-1930s. During this time, an Aboriginal community of over 150 people established itself at Jackson’s Track, setting up camp in the forest and working for Tonkin, felling timber for the mill. Euphemia Mullett was with those people attracted to the promise of work at Jackson’s Track, and she would go on to live there for over thirty years as Tonkin’s wife.

- Book 1 Title: Jackson's Track

- Book 1 Subtitle: Memoir of a Dreamtime place

Jackson’s Track is a disturbing book. The story itself is compelling and, by the book’s close, I felt a fondness and considerable respect for Tonkin and his family. There are very real problems, however, and some of them lie in the manner of this book’s production. This is an assisted autobiography, coproduced by Tonkin and Carolyn Landon, an American living in Australia. Assisted autobiography is inevitably shot through with ethical questions concerning authorship. In the case of Jackson’s Track, though, the matter of authorship is made doubly ambiguous by the oddly shifting credits. Tonkin’s name is given on the cover as the first author, and in larger typeface than Landon’s. But turn to the title page and the order has been reversed; now Landon’s name comes first. By the imprint page, Landon has become the sole author under the National Library’s cataloguing data, with Tonkin under subject.

Certainly Landon’s own description of the processes by which the memoir was produced suggests her substantial involvement in the text:

It was my job to shape what Daryl was telling me, to discover how one event caused another, to figure out motivating/actors in the personalities of the characters that were developing, to define and describe relationships, to work out the historical contexts of events, but not let that intrude too obviously on the memory.

One of the ethical questions raised by Landon’s methods is that the kinds of interventions she has made in the text remain untraceable. As she says, she hoped her intrusions would not be too obvious; she wished to insinuate herself into the body, into the voice box, of her subject: ‘The most important thing was to find the voice, since what I was really trying to do was create an individual human being out of words, Daryl’s words.’

So whose story is Jackson’s Track? In significant ways it is Landon’s, despite the first person pronoun being attributed to Tonkin. The unresolved, even aggravated, ambiguities over authorship have particular implications for this book. Jackson’s Track is a book which declares itself to be centrally concerned with relations between blacks and whites in Australia, and in a text of this nature the authors’ own positioning as racialised subjects needs to be made explicit. Tonkin’s relation to race is made quite evident. Indeed, in many ways it is the subject of the book. And the text generally is fastidious in ‘colouring in’: neither whites nor Aboriginals go racially unmarked in this book. The single exception is Landon herself. Nowhere in the book does she disclose her own racial identity except to say that she is an ‘American’. The absence of explicit self-marking is often itself a marker of whiteness and I have taken Landon to be white. However, it is of critical importance in a book which deals with race relations for its author to mark herself, for otherwise how do we read Landon’s investments in the story she has written? In what ways is she implicated in the representations of race which the book offers? By attempting to write herself out of the text – by trying not to ‘intrude too obviously’ – Landon fails to disclose the way she is herself implicated in race relations and how this may have informed her narrative.

Landon’s is the hand that writes Tonkin’s life story. But of course this is not only Tonkin’s story. It is also, inevitably and inextricably, the story of his Aboriginal wife, Euphemia Mullett, and the nine children they raised, and the Aboriginal community that grew up around the timber mill at Jackson’s Track. However, while the book’s title suggests a memoir of a dreamtime place, this in the end is of course a white man’s dreaming, itself imagined by Landon. This raised the question: what does dreamtime mean in this context? What is at stake in this appropriation of Aboriginal conceptions for what turns out to be a predominantly white-centred history? And, of course, in the uncompromised centrality Landon gives to Tonkin’s perspective she reproduces the very relations the book ostensibly critiques: the centralism and imperialism of dominant white society. One telling example is the efforts the Tonkin family made to place the events of Landon’s narrative into a wider, Aboriginal, context. ‘The Historical Context’, a final chapter provided by Daryl Tonkin and his daughter, Linda Mullett, reminds the reader of some key events in recent Aboriginal history. This part of the story is not integral to Landon’s way of seeing Daryl Tonkin and Jackson’s Track; it is given as an addendum after the epilogue and afterword.

Jackson’s Track attempts to record a very particular time in black-white relations in Victoria, one that has passed irrevocably. However, the Aboriginal presence need not have been evoked so ethereally, so marginally. Aboriginal men and women who lived at Jackson’s Track were alive when Landon and Tonkin began work on the book, but these Aboriginal voices are scarcely sounded in this record. And Euphemia Mullett, whose young face looks out from the cover photograph, is scarcely made present in this memoir. The subtitle of the text – dreamtime place – implicates Mullett who then remains a background figure, barely sketched in, hardly imaginable it seems to Landon. One place, though, where Euphemia seems to have been allowed her voice is in the poignant fragment of a letter she wrote to Daryl Tonkin around the 1940s. This fragment, written in Euphemia’s hand, is reproduced on the back cover. Or is it? It turns out that the letter does not exist. Instead, what is given to us as a document is in fact Tonkin’s recollection of her words forty years after the fact, and then reproduced in another’s hand, presumably in the book designer’s office. In Jackson’s Track, forgery has been mistaken for History’s imaginative practices and the ventriloquist’s tricks for memoir.

Comments powered by CComment