- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I’d spent my childhood and adolescence on this sandy moonscape. I was sure I had something to say about it. I just didn’t know what.’ The book is Robert Drewe’s response to that thought. It is, as he says, a portrait of a place and time. The place is Perth; the time the fifties; the portrait is so very sharp, atmospheric, brutal, and deeply moving. There is a strange and haunting sweetness in the voice of the narrator, a clean, wondering charm. The subtitle of the book is ‘memories and murder’ and, like ghastly mutilations discovered outside the shark net, the murders and other horrible deaths drift before our startled eyes.

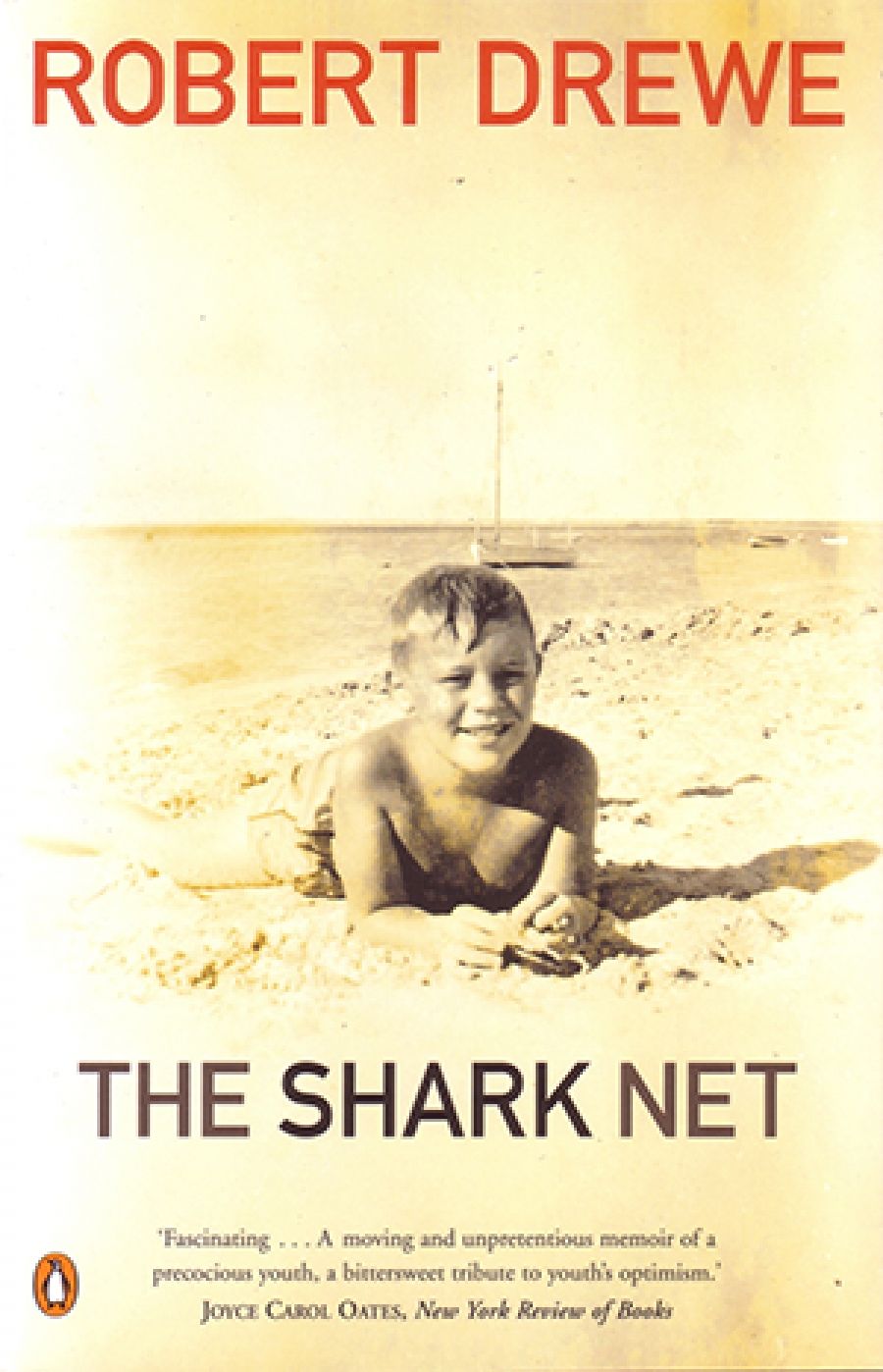

- Book 1 Title: The Shark Net

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $35.00 hb, 358 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/WD6eOX

A serial killer is at large in Perth, disposing in all kinds of ways (guns, cars, knives) of an apparently random selection of innocent and unconnected people. The babysitter is studying on the couch. The killer strolls up and down the street in the storm, walks quietly into the house through an unlocked door, and shoots her in the forehead. The author saves the full identity of the killer till very late in the text, although he begins with the court case, casting a particularly bleak and murky suspense over the whole narrative. There are clear indications to the identity throughout the story, but the reader is compelled to move forward, not dwelling on them, trusting the teller. This is a great skill. The killer’s eye appears at Robert Drewe’s mother’s window one night; and another night the man, with his bandit’s scarf masking his lower face, enters the house but is frightened away. There is an easy familiarity between ordinary people in sedate suburbs and the police – this is a small town in the fifties.

Friends are shot in their sleep; women are raped and dumped on the front lawn. It is the stuff of horror fiction, and so much more horrible because it is told so plainly, paced so carefully, seemingly placed fresh and bleeding before your very eyes. ‘They found her some distance from the house, chopped to death with an axe. The murderer was never found.’ Small notices of violent tragedies speckle the narrative as tensions build within the life of the narrator, are woven darkly into the larger context of brooding malevolence.

There are many, many shocking and appalling moments in this book, but the three which are etched perhaps most deeply on my imagination are these. First, the author’s mother died from a cerebral haemorrhage when she was forty-seven. The description of her funeral, attended only by the males of the family and the company for which the father worked, is one of the very saddest things you can ever read. An eerie nightmare. ‘I looked across the grave at the half-circle of men in business suits, forty or fifty of them, all standing superstitiously back from the grave.’ Some of the men appear to be cynically amused at the tears the author sheds. ‘The stab of hatred I felt for these businessmen then was so sharp it instantly dried my tears.’ This kind of thing simply stops a reader in her tracks.

Second, when the murderer was on death row, his mentally retarded son was taken on a picnic and ‘wandered into the river and drowned’. This is followed by an account of the time when the murderer thought his son showed a glimmer of intelligence. The boy says ‘starfish’ and there follows a sequence of touching and exquisite quiet tragedy, as the moment passes, and the father’s epiphany of love and hope fades. The boy seems to blend into the sand. ‘If you leaned back a bit and half-closed your eyes, the beach absorbed him. It soaked him up.’

Thirdly, there is a surreal scene in which the young narrator goes to the bakery and discovers a ghostly white figure straddling another ghostly white figure. The baker and the one-armed girl who is his assistant, both covered in flour and wearing their baker’s caps, are locked in a vigorous sexual embrace. The girl sees the intruder, shuts her eyes and continues. This is absolutely hideous. ‘Puffs of flour rose as they rode and rocked.’

How can I say, after all that, that this is beautiful? Yet it is beautiful. The steady tone never wavers; there is never a faltering false naivety, something which can dog narratives of childhood reminiscence. Never that. The quiet prose, the open self-exposure, the apparently effortless construction of the narrative produce an effect of poignant and veracious history. Robert Drewe describes the narrative as a track he has chosen to take through the sand dunes. The story emerges with the character of bodies, objects, creatures rising from the dead in the sand. Like the reverse of the time when young Robert carved his name in the limestone foundations of the house, causing the stone to crumble and turn to a rivulet of pale lemon sand. Robert stops it up with a toy car and a little London bus, a screwdriver, cricket ball, and the sprinkler from the garden hose. To form a cement that will hold, he urinates on his work. ‘The entombed offerings held fast.’

We need more history like this.

Comments powered by CComment